Part one of a two-part report

California is a place of extremes. It has beaches, mountains, valleys and deserts. It has glaciers and, just a few miles away, hot, dry deserts. Some years it doesn’t rain. Some years it rains all winter. Those extremes are part of what makes California the attractive place that it is, and, west of the high mountains, California is mostly an extremely comfortable place to live.

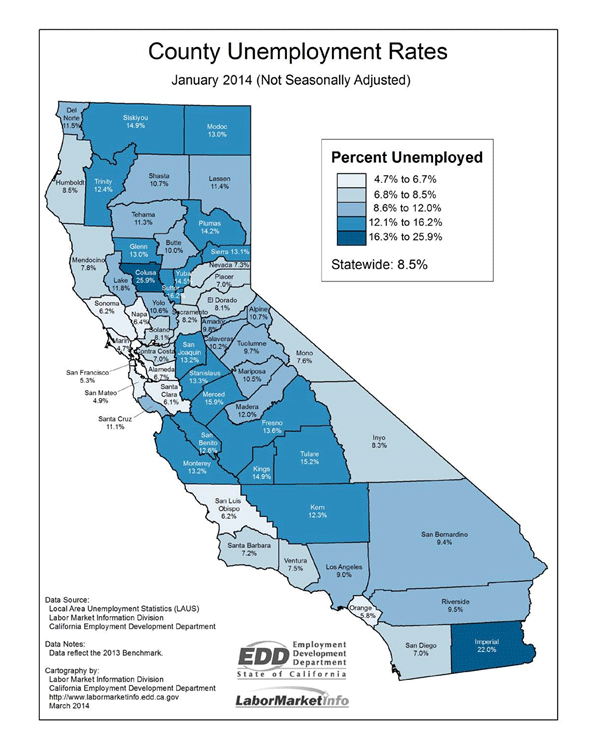

Today, we have some new extremes. Some of our coastal communities are as wealthy as any in the world. At the other extreme, we have some of America’s poorest communities. San Bernardino, for example, has America’s second-highest poverty rate for cities with population over 200,000.

From the beginning, we’ve had the fabulously wealthy. For the first 140 years after gold was found, California was a place where people could find, or, more correctly, build, success. The new part is the poverty. It used to be that the poor were mostly newcomers, people who hadn’t yet had time to show that they had what it takes. Today, our poverty is dominated by families who have been here a long time. While San Bernardino certainly has some newcomers, it is mostly a city of native Californians.

The change became visible in the early 1990s. Many analysts will tell you that the change was caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting peace dividend, which led to a dramatic downsizing of America’s defense sector, once a major component of California’s economy.

I believe the way to think about this is that the downsizing of the defense sector exposed the weaknesses in California’s economy, as opposed to causing them. Sure, the downsizing had an economic impact. California lost hundreds of thousands of jobs. But the defense sector eventually bounced back and again became a source of good jobs. The problem is that it bounced back someplace else. It didn’t come back in California. In fact, it continues to decline in California.

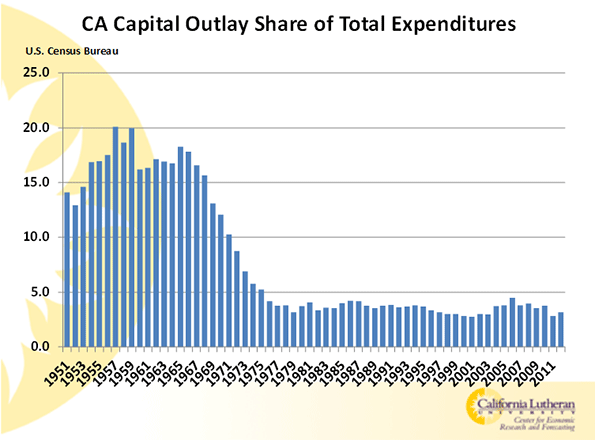

The decline in California’s economic opportunities began way before the 1990s. As the 1960s progressed, Californians, or at the least the ones making decisions, changed their priorities. California’s spending for infrastructure had once consumed between 15 and 20 percent of the State’s budget. It precipitously fell to five percent or below.

In the ’50s and early ’60s, governors Goodwin Knight and Pat Brown presided over a fabulous investment boom in universities, highways, water projects and the like. None of their successors has even attempted anything on that scale. The profound prosperity that accompanied and followed California’s investment boom hid the impacts of subsequent policy changes for decades.

The decline in public capital spending wasn’t the cause of our changed priorities. It was the change in priorities that caused the change in spending. It is as if we decided that we were wealthy enough, and that future spending would be on social and environmental programs. If we weren’t looking for economic growth, why invest?

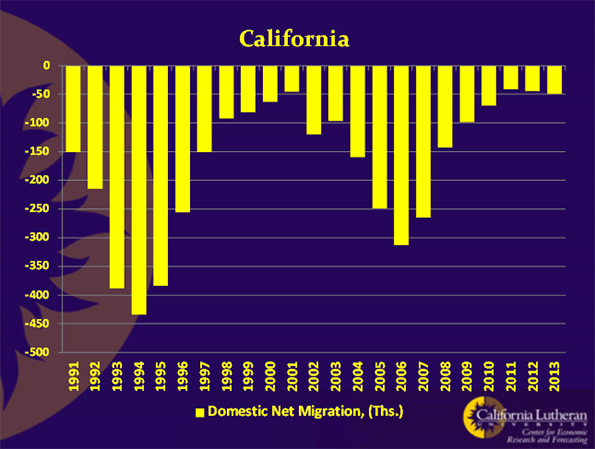

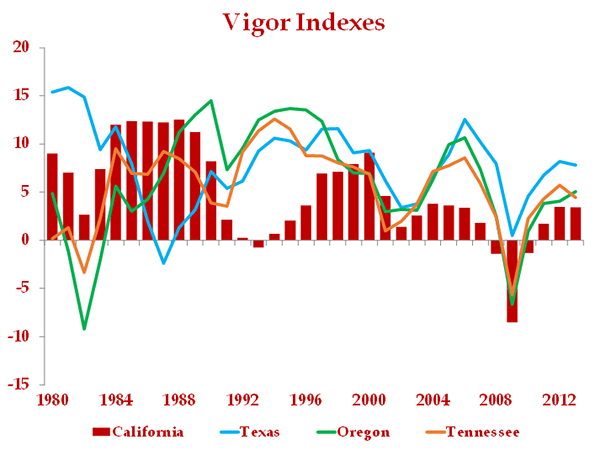

At California Lutheran University’s Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, we’ve created a vigor index. It’s composed of net in-migration, job creation, and new housing permits, each equally weighted. It is quite sensitive to changes in economic opportunity. For example, in 2000, North Dakota had the nation’s lowest score, 0.9, and Nevada led the nation with a score of 24.1. By 2013, North Dakota led the country with a score of 20.0, while Nevada had seen its index value fall to only 6.4.

In the following chart, we show California’s index (red bars) compared to that of Texas, Oregon, and Tennessee, from 1980 through 2013.

California is apparently different than the comparison states. The Tennessee, Oregon, and Texas indexes have behaved more similarly to each other than to California since the late 1980s. Texas’ index behaved uniquely in the early 1980s, because of its dependency on oil and the long-term decline in oil prices that occurred during the 1980s.

California appears to be different than the other states throughout the period, but the nature of the difference has changed. Prior to the late 1980s, California tended to outperform the others. For example, its score didn’t decline nearly as much as the others during the early 1980s recession. Given California’s resource endowment, we think this is natural.

Since 1990, though, California’s vigor index has generally remained below those of Texas, Tennessee, and Oregon. Indeed, since 1990, California’s score has rarely exceeded the score of any of the comparison states, and it has never led them all.

The index also shows that California’s investment in infrastructure during the 1950s and 1960s helped drive economic opportunity for two decades. It took two decades without any investment before we saw the consequences of the decision to not invest.

Recently, California has seen budget surpluses and faster job growth than the average American state. The forces for the status quo now claim that this confirms the wisdom of their policies. They are wrong.

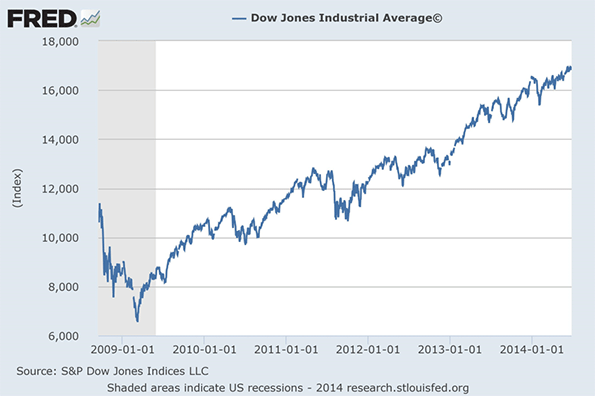

California’s budget surpluses are a product of a temporary tax, and an incredible bull market in equities. Our dependence on a highly progressive income tax means that California’s fiscal condition swings on the fortunes of a small group of wealthy individuals.

Equity markets have been amazing over the past few years. The Dow has increased by over 10,000 since it bottomed out on March 9, 2009, and it appears to be divorced from economic activity. It increases on good news and bad, propelled by an unprecedented monetary expansion. Right now, California’s largest taxpayers are reaping huge profits in the stock markets, and California is reaping huge windfalls in its tax revenues.

Someday, the market gains will cease, or worse reverse. Someday, too, the temporary tax will expire. California’s surpluses will wash away like sand on a beach. The state will face a new crisis, a result of a progressive tax structure where revenues swing on paper profits and losses, not on economic activity.

As for our job gains being better than the average state’s, California should not be average.

Employment should be far higher than it is. Even the weak job growth we’ve seen is largely a legacy of a previous age. California has the world’s best venture capital infrastructure, partly because of the investment previous generations of Californians made in the university system. It is also, in part, a result of chance.

An amazing period of innovation was initiated in Coastal California by a few incredibly talented individuals, who were funded by a few far-sighted capitalists. It was one of those rare coincidences that happen from time to time and change the world. The eventual result was the Silicon Valley and economic powerhouses such as Intel, HP, Apple, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Twitter, and many more.

Another result was the creation of a private, capitalist, vibrant infrastructure. It takes time and vast sums of money before a new idea generates profits. Product design is just the first step. An organization needs to be created to produce and sell the product. Factories need to be designed. Marketing plans need to be put in place.

No inventor or entrepreneur can be expected to have all of the necessary skills or money to turn an idea into a profitable firm. So, an infrastructure appeared. The Silicon Valley’s world-leading venture capital markets and the support structure to enable the fabulous innovation and economic value created there was not the result of any government program or initiative. It was the spontaneous result of lots of people driven to innovate and profit from those innovations. It was capitalism at its very best.

California’s Silicon Valley became the place for talented young people to turn great ideas into reality. It was also the place to go if you had money and wished to invest in vibrant, risky new technologies, or if you knew how to design factories, how to market products, how to build organizations, or how to finance rapid growth. The infrastructure that arose is supporting California today. This amazing capitalist engine of jobs, innovation and wealth is the source of most of California’s economic vigor. But it is a legacy that will eventually slip away, unless California changes its priorities.

This is the first part of a two-part report. Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org.

Flickr photo by mlhradio. A California extreme: Mountains on The Trona-Wildrose Road, at the edge of the Panamint Valley. One of the most remote deserts in North America, in one of the most remote corners of California; the salt flats of Panamint Valley to the west, and Death Valley to the east.