Back in the 1960s, and for well into the 1980s, California stood at the cutting edge of youth culture, the place where trends started and young people clustered. “The California teen, a white, middle-class version of the American dream” raised in a world of “suburbs, cars, and beaches,” notes historian Kirse Granat May, literally shaped the national image of youth, from the Beach Boys and Barbie to Gidget.

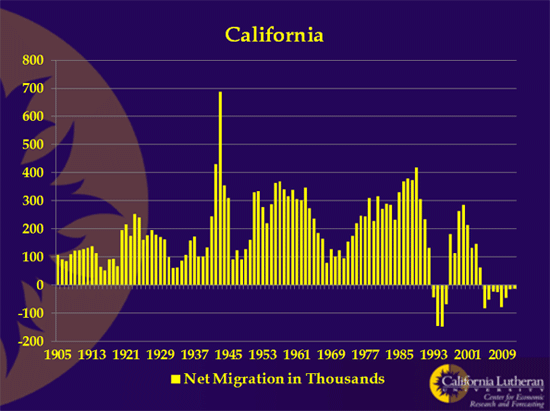

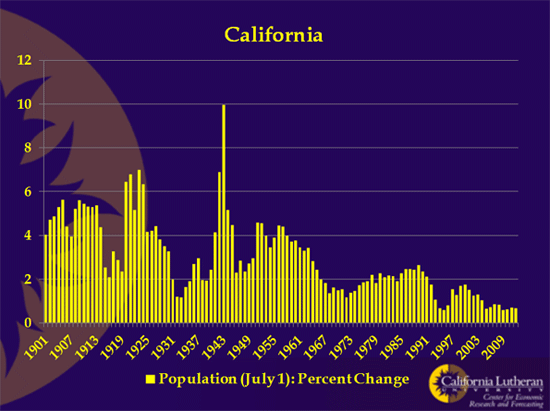

In those times, California, particularly the Southland, was literally becoming ever younger, as more families and migrating 20-somethings moved in. The beaches of Southern California, so attractive to youth, evoked a care-free, athletic, somewhat hedonistic culture; California also was the place where young people, free from the traditional constraints of places East, felt free to innovate, in everything from music and board shorts to the earliest PCs.

Yet today, you increasingly have to color California, particularly Orange and Los Angeles counties, a pale grey. Once evocative of youth, almost mythically so, these counties are aging far faster than the national average. From 2000-12, notes demographer Wendell Cox (www.demographia.com), the average median age of Los Angeles and Orange County residents rose by 10 percent, almost twice the national rate and well above the 6.6 percent rise for the state overall.

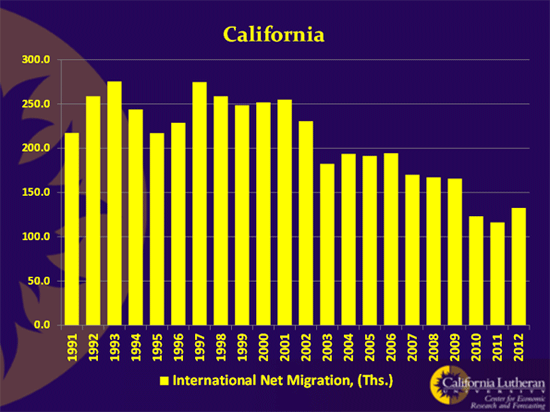

This aging trend will continue, if current conditions remain in place. One recent USC study predicts that the Los Angeles area, due in large part to declining immigration, will continue aging rapidly. In the next two decades, the study projects, Los Angeles County will gain 867,000 senior citizens and have 630,000 fewer residents younger than 25.

In contrast, the Bay Area – even rapidly aging Marin County – has been graying more gradually. In part, the Bay Area’s slower aging is less a reflection of rising birth rates, as was the case in California’s youthful heyday, than the movement of 20-somethings, particularly since 2007. Since then, the San Francisco area has led the nation in migration by the 20-34 age group. It does far worse as people get into prime child-bearing years, ranking 30th in migration among the 52 largest U.S. metropolitan areas.

Not surprisingly, San Francisco – with 80,000 more dogs than kids – has the lowestpercentage of youngsters of any major American city. Even when more-suburban San Mateo County is added, the Bay Area ranks 40th in growth among people under age 4. San Jose-Santa Clara shows a very similar pattern, with people arriving in their 20s and leaving in their child-bearing years.

Southern California right now is not experiencing much youth migration. Hollywood, great weather and the beaches are still all here – in a climate enhanced by a greater cultural diversity – but young people still are not moving here in droves. From 2007-12, this region ranked a mediocre 31st in migration by 20-somethings. Overall, we are losing millennials, while other regions, such as Washington, D.C., Houston, Denver and Austin, Texas, are luring them.

Perhaps even more troubling, the region also ranks 47th for migrants in their prime child-bearing years and 32nd in terms of newborns. If not for the Inland Empire, which does markedly better with the 30- and 40-something groups, Southern California would be starting to look like a multicultural version of supergrey Japan. A recent report for theU.S. Conference of Mayors projected that, by 2042, Los Angeles will rank 58th of 70 U.S. regions for population growth, with the slowest growth of any major city in the South or West.

This low youth migration combined with a steady erosion of the key parental cohorts, suggests that rapid aging could soon replace rambunctious youth as the region’s greatest demographic challenge. An ever-shrinking percentage of families and young workers is not good for the local economy. It deprives local companies of both new employees and an expanding customer base. Older people may be great for lower crime rates and filling hospitals, but not so much for the overall economy, as they often do not work and tend to consume less than younger people.

Why is this occurring, and can anything be done to address this descent into regional senility? One answer lies in the region’s high housing prices. The L.A. area’s median multiple – the ratio of home price to a homeowner’s annual income – is now more thantwice that of more economically dynamic regions like Houston, Austin, Dallas, Atlanta, Nashville, Tenn., and Phoenix.

This price pressure has sharply reduced opportunities for young couples to buy houses, while older residents, often working into their sixties, seventies or even eighties, stay in their homes, further reducing opportunities for the next generation. Mortgage applications have fallen dramatically in recent months, after some signs of resurgence. It’s now largely investors who are holding the market up.

In Southern California, the combination of inflated house prices and weak job growth means not only that fewer young people are coming but, once here, they are having fewer babies, or will move once they take that plunge. This trend is spreading to the Inland Empire, the region’s primary nursery, where declining incomes and higher rents are making family formation an ever-more dicey proposition.

Once a major lure for the parental age groups, the Inland area has dropped to 26th in attracting people in their 30s. This is not surprising given the toxic combination of a weak economy and rising costs; the percentage of Inland Empire households paying at least half their incomes in rent has risen from 20 percent to 30 percent since 2007, a reflection of rising rents amidst shrinking salaries. In Los Angeles, roughly a third of households see half their earnings go to rent.

How can we address this decline? The response of many homebuilders, spurred by the planning agencies, is to reduce the size of houses, even in far-flung suburban areas. This may solve some problems in the eyes of density-obsessed planners but, is not likely to be attractive to families at a time when American house sizes, after a short period of contraction, are expanding again. Less space at higher prices in Southern California may not be so appealing to families who can get more, at lower cost, in a host of markets across the country.

This leaves the Southland with the alternative, seen in the Bay Area, of attracting younger professionals who eventually may leave. But a torpid economy does not help in luring ambitious millennials, and building high-density housing in the absence of expanding incomes and opportunities seems something of a fool’s errand. If they can’t afford the urban-hipster enclaves of New York or San Francisco, the coveted member of the “creative class” may find themselves better off settling first in the burgeoning urban districts of less-expensive cities like Houston, Dallas or Nashville, places where they also can eventually hope to get a decent job and buy a home.

Clearly, this region, with its still-impressive assets, should be attracting both new families as well as younger singles. But this cannot reliably be done unless we begin looking at ways to encourage older people to move out of their homes, perhaps by reforming Proposition 13 and providing other incentives. We could also start allowing builders again to construct the kind of housing families need and clearly want – detached homes where land is affordable. As for the 20-somethings, what they need most is not forced density or transit-oriented development but the whiff of opportunity, something a “smart” policy agenda seems best-suited to stifle.

The premature aging of this region represents an existential challenge, a harbinger of further, long-term decline. Unless addressed by policies that reignite economic growth and expand opportunities, the youthfulness of this region will exist merely a cherished myth, seen in old sitcoms on Nickelodeon but increasingly not in our neighborhoods.

This story originally appeared at The Orange County Register.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.