Even as the troubled economy has continued to hobble along, there may be hints that the domestic migration patterns from before the Great Financial Crisis could be returning at least in some states. This is evident in the recent national interstate migration data from the American Community Survey. This analysis reviews annual interstate migration data from the beginning of the Great Financial Crisis to 2010, with broad comparisons to earlier (2001-2006) data from the Census Bureau population estimates program (Note 1). The big stories are that Florida and Arizona show signs of recovery, the trend has reverted to more negative in California and the steady states are North Carolina (a big gainer of domestic migrants) and Illinois (a big loser of domestic migrants).

Moreover, none of the states that have been perennial domestic migration losers moved into the top ten between 2007 and 2010, even as fast growing states such as Florida and Arizona were hard hit by the real estate bubble and saw migration rates decline. Notably, however, Pennsylvania, which had sustained modest domestic migration losses, rose to the number 8 position in 2010 (Table 1).

| Table | |||

| Top Domestic Migration States: 2001-2010 | |||

| Year and Source | |||

| 2001-6 | 2007-9 | 2010 | |

| Rank | Census Estimates | ACS | ACS |

| 1 | Florida | Texas | Texas |

| 2 | Arizona | North Carolina | North Carolina |

| 3 | Texas | Arizona | Florida |

| 4 | North Carolina | South Carolina | Arizona |

| 5 | Georgia | Georgia | Colorado |

| 6 | Nevada | Oklahoma | South Carolina |

| 7 | South Carolina | Washington | Virginia |

| 8 | Tennessee | Colorado | Pennsylvania |

| 9 | Virginia | Virginia | Washington |

| 10 | Washington | Utah | Kentucky |

The Largest Gaining States:Some of the states with the largest gains seem to be returning toward their previous domestic migration volumes.

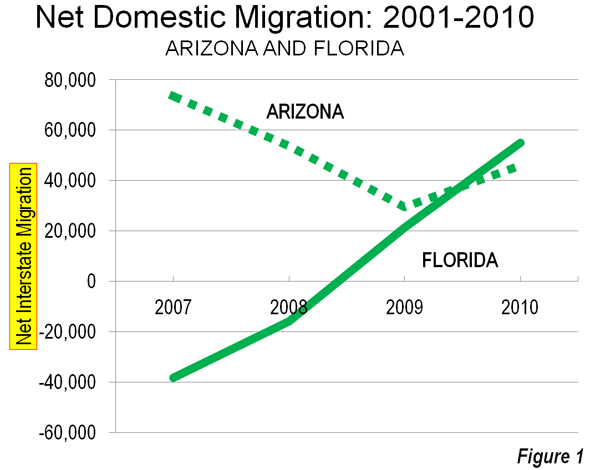

Florida: For the last few years, the big news in interstate domestic migration has been in Florida. This state, which has grown by more than 5.5 times since 1950, had been the domestic migration leader for some years. However, as one of the four "ground zero" states (along with California, Arizona and Nevada) for its huge house price losses, Florida bottomed out at a loss of 38,000 domestic migrants, falling to 44th in 2007. The state lost another 16,000 interstate migrants in 2008. These were the first domestic migration loss since the 1940s for Florida.

However, in 2009, Florida returned to growth, adding 21,000 domestic migrants. An even stronger recovery occurred in 2010, with a net 55,000 domestic migrants. This remains well below the peak of 265,000 recorded in Census estimate figures in 2004 and 2005. Nonetheless, Florida ranked third in domestic migration in 2010, trailing North Carolina by only 1000 as well as number one Texas. Part of Florida’s success is likely related to its housing affordability, which has been restored in all of the state’s major metropolitan areas with the exception of Miami. The recent repeal of Florida’s land rationing "smart growth" law should position the state for even more affordable housing and net domestic migration gains.

Arizona: Arizona is another state that was hit hard by the housing bubble. Much has been written on Arizona’s recent hard times. Yet, unlike Florida, Arizona did not experience domestic migration losses in any year of the past decade. The state has routinely been among the top five in domestic migration, even during the darkest years of the Great Financial Crisis. Like the nation in general, Arizona reached its lowest net domestic migration figure in 2009 at 29,000, but recovered to 46,000 in 2010. Interstate domestic migration remains somewhat below the early 2000s figures, but is trending upwards.

Texas: Texas took the interstate domestic migration crown away from Florida in 2006 at has been the nation’s leader since that time. According to Census estimates, Texas peaked in 2006 at 233,000 net domestic migrants. This was an artificially high peak, location by the outflow of people from Louisiana who were driven out by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and the failure of responsible governments to properly maintain flood control infrastructure. From 2007 to 2009, Texas was also aided by its liberal land use policies that helped it avoid the real estate bubble, retaining lower house prices that made it more attractive to domestic migrants. Texas added more than 125,000 domestic migrants annually. However in 2010, net domestic migration dropped to 75,000. Nonetheless, even Texas indicates a return toward normalcy. In the first five years of the decade, Census data placed net domestic migration in Texas at only 40,000, well short of the 2010 figure.

North Carolina: Through good times and bad, North Carolina was has been a consistent performer among the larger gainers. North Carolina ranked fourth in net domestic migration from 2001 through 2006, according to Census data. Then the state moved up to number two in every year from 2007 to 2010. In 2010 domestic migration was 56,000, slightly below the 2001 to 2006 Census reported average of approximately 63,000. Like Texas, North Carolina largely escaped the real estate bubble, with house prices rising far less severely than on the West Coast, the Northeast, Florida, Nevada and Arizona, which could be a principal reason for its consistent domestic migration gains.

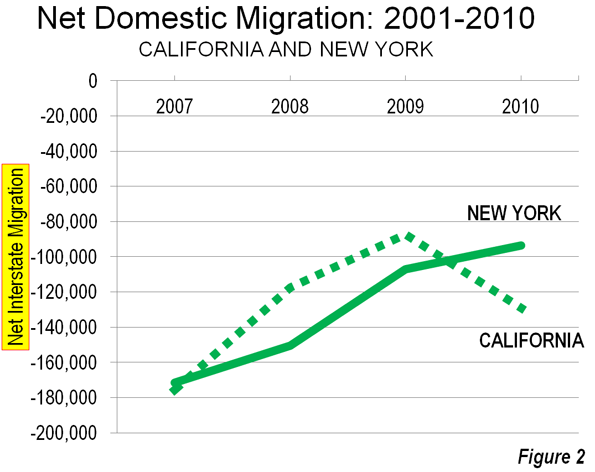

The Largest Losing States:There were also indications that people continue to be among the most significant exports of California and New York, which wrestled for the bottom position for the entire decade. While The New York Times characterized the 2008 to 2010 domestic outmigration from California and New York as having slowed to a "relative trickle," the ACS data indicates that the spigot is still on.

New York:New York experienced a net loss of 94,000 domestic migrants in 2010, a figure nearly equal to the population of its state capital, Albany. Despite this large loss, New York is doing better than earlier in the decade, when domestic outmigration averaged more than 200,000 from 2001 to 2006.

California: California, however, may have taken a turn to the south. After having experienced the largest losses in the nation in 2007 (175,000), net domestic outmigration fell to 87,000 in 2009 and California relinquished the bottom position to New York. However, in 2010, California’s net domestic outmigration rose to 129,000 and the state recovered its former bottom ranking.

Illinois: Illinois has been the most consistent performer among the largest losing states. According to Census data, domestic migration losses averaged 77,000 from 2001 to 2006. ACS data indicates similar losses, averaging 73,000 from 2007 to 2010.

Normalcy Again? It is premature to suggest any long-term judgments on these early data. However, it would not be surprising to see the states with the highest costs of living (driven by high housing costs) and the least friendly business climates to lose domestic migrants to states with lower costs of living and more friendly business environments. For example, the fact that median house prices today in Phoenix are more affordable compared to the large metropolitan areas of coastal California than they were at the peak of the housing bubble may be part of what drove Arizona’s improved net domestic migration in 2010.

—-

Note 1: The Census Bureau provides annual estimates of domestic migration, however does not do so in census years, such as 2010, which is why this analysis uses American Community Survey data. For the purposes of data compatibility, 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010 data from the American Community Survey (also conducted by the Census Bureau) is the principal source for recent trends. This analysis is different from the one by Kenneth M. Johnson of the University of New Hampshire Carey Institute, which detailed domestic migration results from the three year American Community Survey (2008-2010), and which was covered by The New York Times.

Note 2: Leith van Onselen has recently described developments in the Phoenix housing market (in How Phoenix Boomed and Busted) during the last decade.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photograph: Cape Coral, Florida (by author)