In the wake of the Trumpocalypse, many in the deepest blue cores have turned on those parts of America that supported the president’s election, developing oikophobia—an irrational fear of their fellow citizens.

The rage against red America is so strong that The New York Time’s predictably progressive Nick Kristoff says his calls to understand red voters were “my most unpopular idea.” The essential logic—as laid out in a particularly acerbic piece in The New Republic—is that Trump’s America is not only socially deplorable, but economically moronic as well. The kind-hearted blue staters have sent their industries to the abodes of the unwashed, and taken in their poor, only to see them end up “more bitter, white, and alt-right than ever.”

The red states, by electing Trump, seem to have lost any claim on usually wide-ranging progressive empathy. Frank Rich, theater critic turned pundit, turns up his nose at what he calls “hillbilly chic.” Another leftist author suggests that working-class support for Brexit and Trump means it is time “to dissolve” the “more than 150-year-old alliance between the industrial working class and what one might call the intellectual-cultural Left.”

The fondest hope among the blue bourgeoise lies with the demographic eclipse of their red-state foes. Some clearly hope that the less-educated “dying white America,“ already suffering shorter lifespans, in part due to alcoholism and opioid abuse, is destined to fade from the scene. Then the blue lords can take over a country with which they can identify without embarrassment.

Marie Antoinette Economics

In seeking to tame their political inferiors, the blue bourgeoisie are closer to the Marie Antoinette school of political economy than any traditional notion of progressivism. They might seek to give the unwashed red masses “cake” in the form of free health care and welfare, but they don’t offer more than a future status as serfs of the cognitive aristocracy. The blue bourgeoisie, notes urban analyst Aaron Renn, are primary beneficiaries of “the decoupling of success in America.” In blue America, he notes, the top tiers “no longer need the overall prosperity of the country to personally do well. They can become enriched as a small, albeit sizable, minority.”

Some on the left recognize the hypocrisy of progressives’ abandoning the toiling masses. “Blue state secession is no better an idea than Confederate secession was,” observes one progressive journalist. “The Confederates wanted to draw themselves into a cocoon so they could enslave and exploit people. The blue state secessionists want to draw themselves into a cocoon so they can ignore the exploited people of America.”

Ironically, many of the most exploited people reside in blue states and cities. Both segregation and impoverishment has worsened during the decades-long urban “comeback,” as even longtime urban enthusiast Richard Florida now notes. Chicago, with its soaring crime rates and middle class out-migration, amidst a wave of elite corporate relocations, epitomizes the increasingly unequal tenor of blue societies.

In contrast the most egalitarian places, like Utah, tend to be largely Trump-friendly. Among the 10 states (and D.C.) with the most income inequality, seven supported Clinton in 2016, while seven of the 10 most equal states supported Trump.

If you want to see worst impacts of blue policies, go to those red regions—like upstate New York—controlled by the blue bourgeoise. Backwaters like these tend to be treated at best as a recreational colony that otherwise can depopulate, deindustrialize, and in general fall apart. In California, much of the poorer interior is being left to rot by policies imposed by a Bay Area regime hostile to suburban development, industrial growth, and large scale agriculture. Policies that boost energy prices 50 percent above neighboring states are more deeply felt in regions that compete with Texas or Arizona and are also far more dependent on air conditioning than affluent, temperate San Francisco or Malibu. Six of the 10 highest unemployment rates among the country’s metropolitan areas are in the state’s interior.

Basic Errors in Geography

The blue bourgeoisie’s self-celebration rests on multiple misunderstandings of geography, demography, and economics. To be sure, the deep blue cites are vitally important but it’s increasingly red states, and regions, that provide critical opportunities for upward mobility for middle- and working-class families.

The dominant blue narrative rests on the idea that the 10 largest metropolitan economies represents over one-third of the national GDP. Yet this hardly proves the superiority of Manhattan-like density; the other nine largest metropolitan economies are, notes demographer Wendell Cox, slightly more suburban than the national major metropolitan area average, with 86 percent of their residents inhabiting suburban and exurban areas.

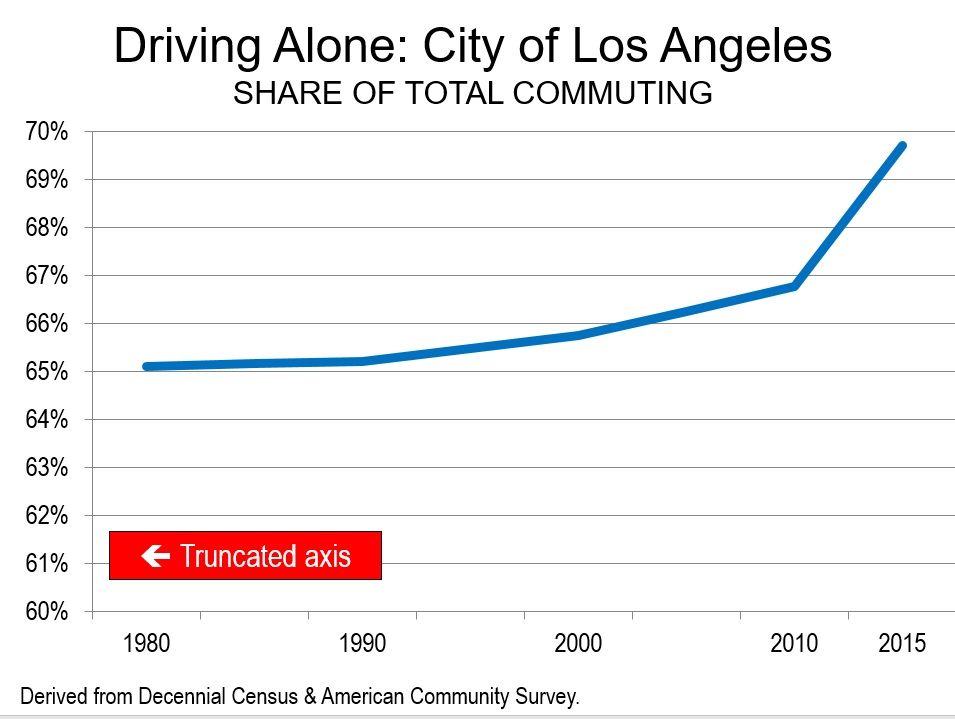

In some of our most dynamic urban regions, such as Phoenix, virtually no part of the region can be made to fit into a Manhattan-, Brooklyn-, or even San Francisco-style definition of urbanity. Since 2010 more than 80 percent of all new jobs in our 53 leading metropolitan regions have been in suburban locations. The San Jose area, the epicenter of the “new economy,” may be congested but it is not traditionally urban—most people there live in single-family houses, and barely 5 percent of commuters take transit. Want to find dense urbanity in San Jose? You’ll miss it if you drive for more than 10 minutes.

The argument made by the blue bourgeoisie is simple: Dense core cities, and what goes on there, is infinitely more important, and consequential, than the activities centered in the dumber suburbs and small towns. Yet even in the ultra-blue Bay Area, the suburban Valley’s tech and STEM worker population per capita is twice that of San Francisco. In southern California, suburban Orange County has over 30 percent more STEM workers per capita than far more urban Los Angeles.

And it’s not just California. Seattle’s suburban Bellevue and Redmond are home to substantial IT operations, including the large Microsoft headquarters facility. Much of Portland’s Silicon Forest is located in suburban Washington County. Indeed a recent Forbes study found that the fastest-growing areas for technology jobs outside the Bay Area are all cities without much of an urban core: Charlotte, Raleigh Durham, Dallas-Fort Worth, Phoenix, and Detroit. In contrast most traditionally urban cities such as New York and Chicago have middling tech scenes, with far fewer STEM and tech workers per capita than the national average.

The blue bourgeois tend to see the activities that take place largely in the red states—for example manufacturing and energy—as backward sectors. Yet manufacturers employ most of the nation’s scientists and engineers. Regions in Trump states associated with manufacturing as well as fossil fuels—Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Detroit, Salt Lake—enjoy among the heaviest concentrations of STEM workers and engineers in the country, far above New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles.

Besides supplying the bulk of the food, energy, and manufactured goods consumed in blue America, these industries are among the country’s most productive, and still offer better paying options for blue-collar workers. Unlike a monopoly like Microsoft or Google, which can mint money by commanding market share, these sectors face strong domestic and foreign competition. From 1997-2012, labor productivity growth in manufacturing—3.3 percent per year—was a third higher than productivity growth in the private economy overall.

For its part, the innovative American energy sector has essentially changed the balance of power globally, overcoming decades of dependence on such countries as Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Venezuela. Agriculture—almost all food, including in California, is grown in red-oriented areas—continues to outperform competitors around the world.

Exports? In 2015, the U.S. exported $2.23 trillion worth of goods and services combined. Of the total, only $716.4 billion, or about a third, consisted of services. In contrast, manufactured goods accounted for 50 percent of all exports. Intellectual property payments, like royalties to Silicon Valley tech companies and entrepreneurs, amounted to $126.5 billion—just 18 percent of service exports and less than 6 percent of total exports of goods and services combined, barely even with agriculture.

Migration and the American Future

The blue bourgeoisie love to say “everyone” is moving back to the city; a meme amplified by the concentration of media in fewer places and the related collapse of local journalism. Yet in reality, except for a brief period right after the 2008 housing crash, people have continued to move away from dense areas.

Indeed the most recent estimates suggest that last year was the best for suburban areas since the Great Recession. In 2012, the suburbs attracted barely 150,000 more people than core cities but in 2016 the suburban advantage was 556,000. Just 10 of the nation’s 53 largest metropolitan regions (including San Francisco, Boston, and Washington) saw their core counties gain more people than their suburbs and exurbs.

Overall, people are definitively not moving to the most preferred places for cosmopolitan scribblers. Last year, all 10 of the top gainers in domestic migration were Sun Belt cities. The list was topped by Austin, a blue dot in its core county, surrounded by a rapidly growing, largely red Texas sea, followed by Tampa-St. Petersburg, Orlando, and Jacksonville in Florida, Charlotte and Raleigh in North Carolina, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and San Antonio.

Overall, domestic migration trends affirm Trump-friendly locales. In 2016, states that supported Trump gained a net of 400,000 domestic migrants from states that supported Clinton. This includes a somewhat unnoticed resurgence of migration to smaller cities, areas often friendly to Trump and the GOP. Domestic migration has accelerated to cities between with populations between half a million and a million people, while it’s been negative among those with populations over a million. The biggest out-migration now takes place in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York.

Of course, for the blue cognoscenti, there’s only one explanation for such moves: Those people are losers and idiots. This is part of the new blue snobbery: Bad people, including the poor, are moving out to benighted places like Texas but the talented are flocking in. Yet, like so many comfortable assertions, this one does not stand scrutiny. It’s the middle class, particularly in their childbearing years, who, according to IRS data, are moving out of states like California and into ones like Texas. Since 2000, the Golden State has seen a net outflow of $36 billion dollars from migrants.

Millennials are widely hailed as the generation that will never abandon the deep blue city, but as they reach their thirties, they appear to be following their parents to the suburbs and exurbs, smaller cities, and the Sun Belt. This assures us that the next generation of Americans are far more likely to be raised in Salt Lake City, Atlanta, the four large Texas metropolitan areas, or in suburbs, than in the bluest metropolitan areas like New York, Seattle, or San Francisco—where the number of school-age children trends well below the national average.

This shift is being driven in large part by unsustainable housing costs. In the Bay Area, techies are increasingly looking for jobs outside the tech hub and some companies are even offering cash bonuses to those willing to leave. A recent poll indicated that 46 percent of millennials in the San Francisco Bay Area want to leave. The numbers of the “best and brightest” have been growing mostly in lower-cost regions such as Austin, Orlando, Houston, Nashville, and Charlotte.

Quality of Life: The Eye of the Beholder

Ultimately, in life as well as politics, people make choices of where to live based on economic realities. This may not apply entirely to the blue bourgeoisie, living at the top of the economic food chain or by dint of being the spawn of the wealthy. But for most Americans aspiring to a decent standard of living—most critically, the acquisition of decent living space—the expensive blue city simply is not practicable.

Indeed, when the cost of living is taken into consideration, most blue areas, except for San Jose/Silicon Valley, where high salaries track the prohibitive cost of living, provide a lower standard of living. People in Houston, Dallas, Austin, Atlanta, and Detroit actually made more on their paychecks than those in New York, San Francisco, or Boston. Deep-blue Los Angeles ranked near the bottom among the largest metropolitan areas.

These mundanities suggest that the battlegrounds for the future will not be of the blue bourgeoisie’s choosing but in suburbs, particularly around the booming periphery of major cities in red states. Many are politically contestable, often the last big “purple” areas in an increasingly polarized country. In few of these kinds of areas do you see 80 to 90 percent progressive or conservative electorates; many split their votes and a respectable number went for Trump and the GOP. If the blue bourgeoisie want to wage war in these places, they need to not attack the suburban lifestyles clearly preferred by the clear majority.

Blue America can certainly win the day if this administration continues to falter, proving all the relentless aspersions of its omnipresent critics. But even if Trump fails to bring home the bacon to his supporters, the progressives cannot succeed until they recognize that most Americans cannot, and often do not want to, live the blue bourgeoisie’s preferred lifestyle.

It’s time for progressives to leave their bastions and bubbles, and understand the country that they are determined to rule.

This piece first appeared on The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, was published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo: Rafał Konieczny (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons