When I arrived in Los Angeles four decades ago, it was clearly a city on the rise, practicing its lines on the way to becoming the dominant metropolis in North America. Today, the City of Angels and much of Southern California lag behind not only a resurgent New York City, but also L.A.’s longtime regional rival, San Francisco, both demographically and economically.

Forty years ago, San Francisco was a quirky, backward-looking town, a haven for the gilded rich and hippies, a quaint but increasingly insignificant town. The Dodgers and the Lakers ruled the California sporting world.

Today things couldn’t be more different. San Francisco and its much bigger southerly neighbor, Silicon Valley, have morphed into the global epicenter of the technology industry, with 25 tech companies on the Fortune 500. In contrast, Los Angeles County, which has almost twice as many people, is home to only 15 Fortune 500 firms total.

Meanwhile, the Giants and the Golden State Warriors have become consistent winners while the Dodgers, Angels and Clippers disappoint and the Lakers are painfully unwatchable.

Although there is a desire to repeat L.A.’s success with the 1984 Olympics and bring football back to town, that would only put a happy veneer over the city’s core problem: the long-term decline of its business sector. In 1984, the city had a strong and highly motivated business elite highlighted by 12 Fortune 500 companies, who could help sponsor the games and provide management expertise. Now there are only three within city limits, with the departure of major corporations such as Lockheed, Northrop Grumman, Occidental Petroleum and Toyota, and the loss of hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs.

In contrast, the Bay Area is full of thriving companies and successful entrepreneurs, many of them astoundingly young. Of the 30 richest people in the country, five live in the Bay Area; Southern California has only one, the Irvine Company visionary Chairman Donald Bren, and he’s in his eighties. The Bay Area accounts for the vast majority of American billionaires under 40; if not for Snapchat’s founders, Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy, as well Elon Musk, who lives in L.A. but spends much of his time working in Northern California, where Tesla and Solar City are located, L.A. would be off the list.

This unfavorable contrast with the Bay Area, sadly, is not just a recent development. Since 1990 Los Angeles County has added a paltry 34,000 jobs while its population has grown 1.2 million. In contrast, the Bay Area, which added roughly the same number of people during the same time, gained a net 500,000 jobs, mostly in the suburbs. In 1990 Los Angeles had around the same number of private-sector jobs per person as the Bay Area, roughly 410 per 1,000; today Los Angeles’ private-sector jobs to population ratio has dropped to 364 per 1,000 while the Bay Area’s has grown to 415. Worse yet, while the Bay Area has increased its share of high-wage jobs to 33 percent since 1990, Los Angeles percentage fell to 27.7 percent.

How L.A. Blew It In Technology

As recently as the 1970s, as UCLA’s Michael Storper has pointed out, L.A. stood on the cutting edge not only in hardware, but also software. Computer Sciences Corp. was the first software company to be listed on a national stock exchange. In 1969, UCLA’s Leonard Kleinrock invented the digital packet switch, one of the keys to the Internet.

In 1970, IT’s share of the economy in greater Los Angeles and in the Bay Area was about the same (in absolute terms it was bigger in L.A.). By 2010, IT’s share was four times bigger in the north than in the south.

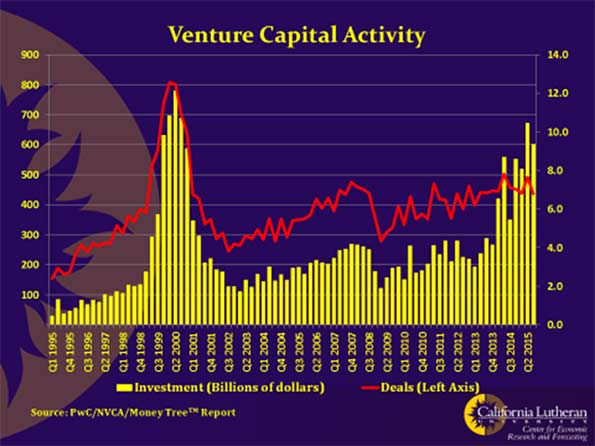

Storper links the decline in large part to the strategies of the biggest high-tech companies in the L.A. area: Lockheed Martin, Rockwell and TRW focused on defense and space, essentially becoming dependent on government spending. In contrast, the Bay Area technology community, although also initially tied to Washington, began to move into more commercial applications. In the process they also developed a huge network of venture capitalists who would continue to help found and finance fledgling firms.

Today the San Jose area enjoys the highest percentage of workers in STEM (science technology engineering and mathematics-related jobs) in the country, over three times the national average. San Francisco and its immediate environs, largely as a result of the social media boom, now has a location quotient for STEM jobs of 1.75, meaning it has 75% more tech jobs per capita than the national average. In contrast, the Los Angeles area barely makes it to the national average.

Southern California remains an attractive to place to live, but it’s hard to imagine it as the next Silicon Valley. L.A. had its chance, and, sadly, it blew it.

The Growing Demographic Crisis

Storper and other critics suggest that Los Angeles failed in part because it tried to maintain high-wage blue collar industries while the Bay Area focused on information and biotechnology. The problem now, however, are the factors in L.A. that drive industry away, such as ultra-high electricity prices and a high level of regulation. Even amidst the recent industrial boom in many other parts of the country, Los Angeles has continued to lose manufacturing jobs; Los Angeles’ industrial job count stands at 363,900, still the largest number in the nation, but down sharply from 900,000 just a decade ago.

This decline places L.A in a demographic dilemma. Like the Midwestern states that lured African-American to fill industrial jobs during the Great Migration, L.A. attracted a large number of largely poorly educated immigrants, mostly from Mexico and Central America. These people came for jobs in factories, logistics and home-building, but now find themselves stranded in an economy with little place for them outside low-end services.

Although inequality and racial disparities also exist in the Bay Area, the issue is far more relevant in Southern California. The Bay Area’s population is increasingly dominated by well-educated Anglos and Asians. San Francisco’s population is 22 percent black or Hispanic; in Los Angeles, this percentage approaches 60 percent.

Poverty and lack of upward mobility are the biggest threats to the region. In Los Angeles, a recent United Way study found 35 percent of households were “struggling,” essentially living check to check, compared to 24 percent for the Bay Area.

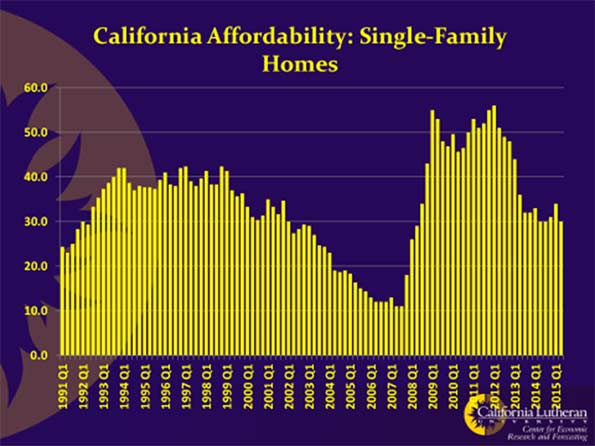

A recent study by the Public Policy Institute of California and the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality found that, once adjusted for cost of living, Los Angeles has the highest level of poverty in the state, 26.1 percent. Rents are out of control for many people who are struggling in an increasingly low-wage dominated economy. In fact, Los Angeles now is the least affordable city for renters, based on income, according to a recent UCLA paper.

Is There A Way Out?

Despite these myriad challenges, Los Angeles, and indeed all of Southern California, is far from a hopeless case. It is unlikely to become the next Detroit and is better positioned by natural and human resources than it’s similarly troubled big city competitor Chicago. It still enjoys arguably the best climate of any major city in the world, remains the home of Hollywood, the nation’s dominant ports and a still impressive array of hospitals and universities.

At least some of the city’s leadership has begun to recognize the challenges facing the region. “The city where the future once came to happen,” a devastating blue ribbon report recently intoned, “is living the past and leaving tomorrow to sort itself out.”

This recognition might be the first step toward a turnaround, but the area really has increasingly little control over its own fate. Today San Francisco and its immediate environs, despite its much smaller population, is home to virtually every powerful politician in the state: both its U.S. Senators, the Governor, the Lieutenant Governor and the Attorney General. Not surprisingly, state policies on everything from greenhouse gases, urban density and transit to social issues follows lines that originate in, and largely benefit, San Francisco.

Most troubling of all, the local leadership seems clueless about how to resuscitate the economy, or even how this vast region actually operates. Neither another Olympics nor getting a football team or two will make a difference. Even worse is the effort by Mayor Eric Garcetti to densify the city to resemble a sun-baked version of New York.

This has been part of the agenda for developers, greens and most local academics for the better part of 30 years. But the problem remains: Los Angeles, and even more so its surrounding region, is notNew York, nor can it ever be. It is, and will remain, a car-dominated, multi-polar city for the foreseeable future. After all the vast majority of Southern California’s population growth — roughly 75 percent — came after the Second World War and the demise of the Red Cars, L.A.’s much lamented pre-war transit system.

Some outside observers such as progressive blogger Matt Yglesias now envision L.A. as “the next great transit city.” Yet in reality, despite spending $10 billion on new transit projects, the share of transit commuters has actually dropped since 1990; today nearly 31 percent of New York area commuters take public transportation, while 6.9 percent do so in Los Angeles-Orange County.

People take cars because, for most, it’s the quickest way to work. Few transit trips take less time, door to door than traveling by car, not to mention the convenience of working at home. The average transit rider in Los Angeles spends 48 minutes getting to work, compared to people driving alone, at 27 minutes.

This reflects L.A.’s great dispersion of employment, which is not compatible with a transit-driven culture. In greater New York, 20 percent of the workforce labors in the central core; in San Francisco, the percentage is roughly 10 percent. But barely 2 percent do so in Los Angeles. The current, much ballyhooed revival of downtown Los Angeles then is less a reflection of economic forces, than the preferences of a relatively small portion of population for a more urban lifestyle and as market for Asian flight capital. Its population of 50,000 is about the same as Sherman Oaks or the recently minted city of Eastvale in the Inland Empire.

Rather than seek to become someplace else, Los Angeles has to confront its key problems, like its woeful infrastructure, particularly roads, among the worst in the country, and a miserable education system. These are among the likely reasons why people with children are leaving Los Angeles faster than any major region of the country.

Yet Los Angeles is not without allure. Overall Los Angeles-Orange has grown its ranks of new educated workers between 25 and 34 since 2011 as much as New York and San Francisco and much more than Portland.

Perhaps most promising is the region’s status as the number one producer of engineers in the country, almost 3,000 annually. This raw material is now being somewhat wasted, with as many as 70 percent leaving town to find work.

What Los Angeles needs to do is to provide the entrepreneurial opportunities to keep its young at home, particularly the tech oriented. As the Bay Area has shown, it is possible to reshape an economy based on pre-existing strength. For L.A. the best regional strategy would be based on a remarkably diverse economy dominated by smaller firms, a population that, for the most part, seeks out quiet residential neighborhoods and often prefers working closer to home than battling their way to what remains a still unexceptional downtown.

One place where Los Angeles could shine is in melding the arts and technology. Unlike New York, which has relatively few engineers, Los Angeles still has the largest supply in the country. The Bay Area may be more appealing to nerddom, but is unexceptional in the arts. This revival will not come from the remaining suits in L.A.; roughly half of workers in the arts are self-employed, according to the economic forecasting firm EMSI.

This entrepreneurial trend will continue since, with the studio system clearly in decline, as large productions go elsewhere, digital players such as Netflix, Amazon, Apple as well as Los Angeles based Hulu have become more important. Los Angeles could expand its arts-related niche by supplying the content that these expanding digital pipelines require.

Given the corporate exodus, and the difficult California business climate, overall L.A.’s recovery must come from the bottom up, and be dispersed throughout the region. According to Kauffman Foundation research, the L.A. area already has the second highest number of entrepreneurs per 100 people in the country, just slightly behind the Bay Area.

The next L.A. can succeed, but not by trying to duplicate New York or San Francisco. Instead there’s a need for greater appreciation why so many millions migrated here in the first place: great weather, beaches, suburban-like living and entrepreneurial opportunities. Only when the local leadership rediscovers the uniqueness of L.A.’s DNA can the region undergo the renaissance of this most naturally blessed of places.

This article first appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo: Downtown Los Angeles toward the Hollywood Hills and the San Fernando Valley (by Wendell Cox)