The California Department of Finance (DOF) has issued population projections for the state’s counties to 2060. Forecasts are provided for every decade, from a 2010 base. The DOF projects that the the state will grow from 37.3 million residents in 2010 to 51.7 million in 2060. This is a 0.7 percent annual growth rate over the next 50 years. By contrast, California’s growth rate was 1.7 percent annually over the last 50 years (1960-2010), and a much higher 3.0 percent in the growth heyday of 1940 to 1990. However, even with this slower rate, California is expected to grow slightly more quickly than the nation (0.6 percent annually).

The current projections are considerably more conservative than those made by DOF less than a decade ago. In 2007, DOF forecast that California would have 60 million residents in 2050. The current population project for 2050 is substantially smaller, at 49.8 million.

Metropolitan Complexes

To understand where this growth is projected to take place — and not — we look at CSA’s (consolidated statistical areas). CSA’s are economically connected, adjacent metropolitan areas. CSA’s require a 15 percent employment interchange between the metropolitan areas. Metropolitan areas themselves are defined by a 25 percent commuting interchange between outlying counties and central counties, each of which must have at least one-half of its population in the core urban area.

As Michael Barone pointed out in his analysis of the 2014 population estimates, sometimes it is not obvious when one metropolitan area changes into another, as in the cases of San Francisco/San Jose and Los Angeles/Riverside-San Bernardino, which are CSA’s. Another example is New York and the southwestern Connecticut suburbs in Fairfield and New Haven counties. This is because there is no break in the continuous urbanization.

Metropolitan Complexes in 2060

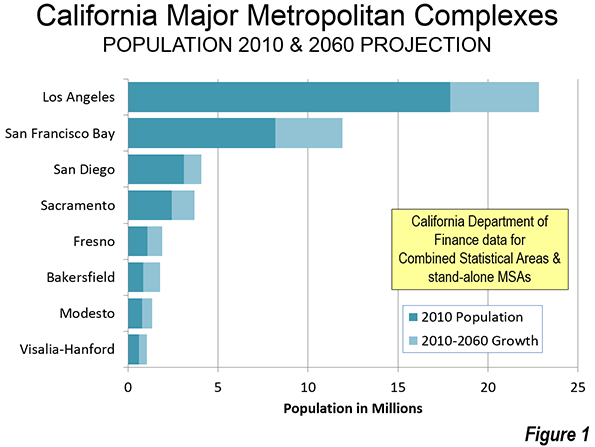

If the DOF has it right, in a half century, California will be home to eight major metropolitan complexes. which I am defining as combined statistical areas (CSA’s) or "stand alone" metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population (Figure 1).

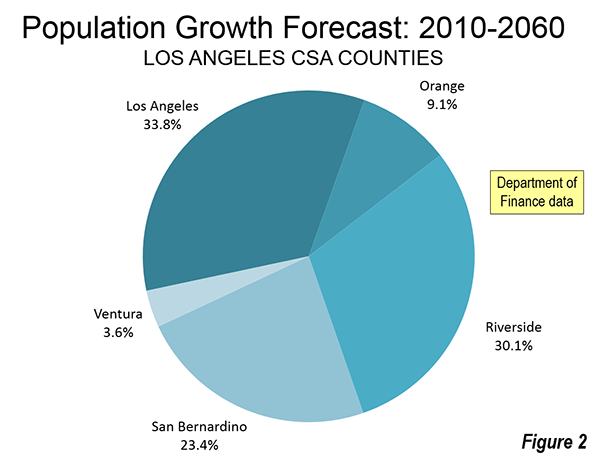

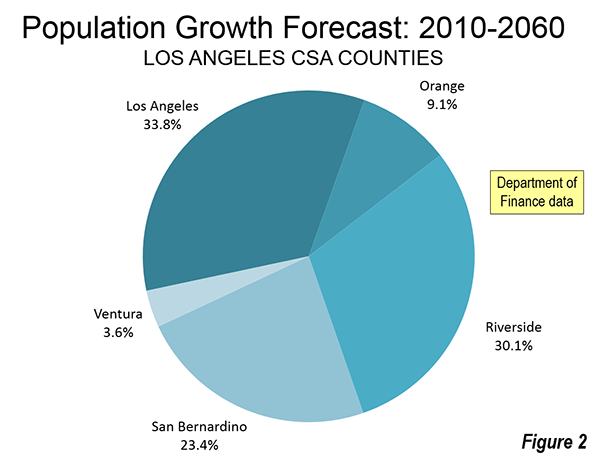

The Los Angeles metropolitan complex (Los Angeles-Riverside, including Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties) would remain by far the largest, growing from 17.9 million to 22.8 million. One-third of the growth would be in Los Angeles County, and two-thirds outside. Riverside and San Bernardino counties would receive most of the growth (53 percent). Riverside County would grow the fastest, adding 68 percent to its population (Figure 2). Overall, the Los Angeles metropolitan complex would grow 27.3 percent, well below the projected state rate of 38.4 percent. This is quite a turnaround for a metropolitan complex that was once among the fastest growing in human history.

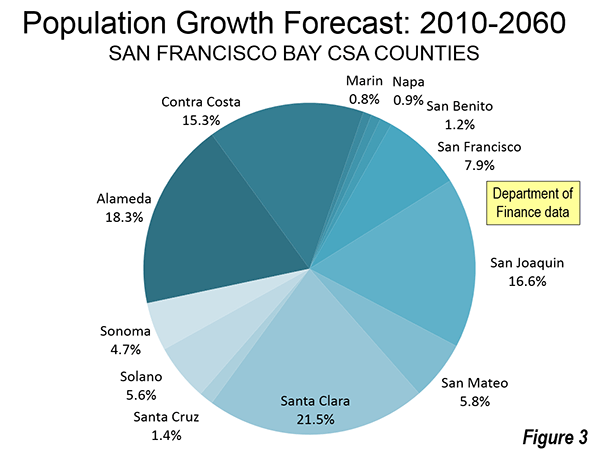

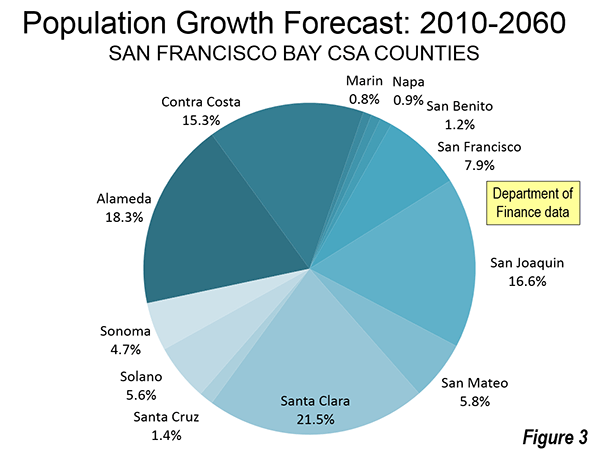

The San Francisco Bay metropolitan complex, including the San Francisco, San Jose, Santa Cruz, Vallejo, Santa Rosa and Stockton metropolitan areas would grow a much faster 45.6 percent, from 8.1 million in 2010 to 11.9 million in 2060. The core city of San Francisco would add nearly 300,000, growing 36.3 percent to 1.1 million, (nearly the state rate). However, only 8 percent of the Bay Area growth would be in San Francisco, and 92 percent outside (Figure 3). Four counties would add more than 500,000 residents, including Santa Clara (800,000), Alameda (680,000), Contra Costa (519,000), and newly added San Joaquin county, which is defined as the Stockton metropolitan area (620,000). San Joaquin County would also grow the fastest, at 90 percent, reaching 1.3 million. This growth is to be expected, since San Joaquin is one of the more peripheral counties, and where the metropolitan fringe (which includes the commuting shed) has been expanding the most.

The San Diego metropolitan complex, a "stand alone" metropolitan area, would grow nearly as slowly as Los Angeles. San Diego’s population of 3.1 million in 2010 would rise to 4.1 million in 2060, an increase of 30.8 percent.

Sacramento’s metropolitan complex includes the Sacramento, Truckee-Grass Valley and Yuba City metropolitan areas. Sacramento is projected to grow 52.8 percent, from 2.4 million in 2010 to 3.7 million in 2060.

Four additional metropolitan complexes with more than 1 million population are projected, all in the San Joaquin Valley.

Fresno, which includes Fresno County and Madera County, would grow from 1.1 million to 1.9 million, for a nearly 75 percent growth rate.

Bakersfield (Kern County) would be the fastest growing among major metropolitan complexes. Bakersfield would grow from 840,000 in 2010 to 1.8 million in 2060, for a growth rate of 111 percent.

Modesto (Stanislaus and Merced counties) would be the seventh largest metropolitan complex. From a 2010 population of 770,000, Modesto would grow 74 percent to 1,340,000. However, it is possible that by 2060 the commuting shed will reach the San Francisco Bay metropolitan complex, causing it to consume Modesto, as it already has Stockton.

In 2060, California would get its eighth major metropolitan area, with Visalia-Hanford reaching 1,040,000, up 74 percent from 2010 (Tulare and Kings Counties).

Outside of these areas, the largest metropolitan complex would be Salinas, which is projected to have 530,000 residents by 2060. However, Salinas is close enough to the San Francisco Bay Area that it could be added to that area’s commuting shed by 2040. The next largest metropolitan area would be El Centro (Imperial County), with a population projected to reach 340,000 by 2060. El Centro, however, could be included in the San Diego commuter shed by that time, making it a part of the San Diego metropolitan complex. The next largest metropolitan complexes would be in the northern Sacramento Valley, Redding and Chico, both approximately 300,000.

Only 2.4 million Californians lived outside the 8 major metropolitan complexes, or 7 percent of the population. Growth in these areas is expected to be slow, with only a 27 percent increase to 2060.

The Difficulty of Projections

Of course, it is virtually impossible to accurately predict demographic trends 50 years into the future. California’s slower than expected growth in recent decades reflected general economic weakness since 1990, and the impact of ultra-high housing prices, particularly on the coast. However, the 2060 California projections provide an interesting view of the future from today’s perspective.

Photo: Bakersfield: Fastest Growth Projected 2010 to 2060. “Bakersfield CA – sign” by nickchapman – originally posted to Flickr as P1000493. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris. Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism and is a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University.