The Globe and Mail, a Canadian national newspaper, reports concerns raised by Magna International, Inc. that proposed provincial labor legislation (the “Fair Workplaces Better Jobs Act”) could result in seriously reduced economic competitiveness for Ontario, Canada’s most populous province (“Magna says new Ontario labour bill threatens jobs, investment”). Ontario accounts for about 40 percent of the Canadian economy and has approximately twice the gross domestic product of second ranking Québec. Magna is Canada’s largest employer in the automotive sector, which The Globe and Mail characterizes as “one of a handful of homegrown Canadian companies that have risen to the status of global giants.”

Magna told the provincial parliamentary standing committee on finance that “For the first time in our 60 year history, we find ourselves in the very untenable position questioning whether we will be able to operate at historical levels in this province.” Stressing the need to remain competitive, the company added: “This is especially important when our main competitor to the south is working harder than ever to reduce costs, regulatory burdens and promote business efficiency and productivity. From our perspective, the province of Ontario seems to be moving in the opposite direction.”

The proposed legislation would increase mandatory annual vacation and personal leave requirements and increase the minimum wage. The legislation would also reduce work scheduling flexibility. This would, according to Magna, make the “just in time” production “impossible,” in a North American industry that has used the practice to compete more effectively. According to Automotive News, Magna noted the difficulty of manufacturing where it calls the cost of electricity, payroll and pension costs and the provincial “cap and trade” policy are among the highest in the G-7. Magna said that the “Fair Workplaces Fair Jobs Act” is “extremely one-sided.

At the same time that Ontario seems poised to make business investment more difficult, some key nearby US states are doing the opposite. Michigan, Indiana and Kentucky, all on the NAFTA Highway (Interstate 69) have enacted voluntary unionism laws (called “right to work”). Ohio has reduced taxes among the most of any state over the past five years. None of these states seems inclined to follow Ontario’s example. Another nearby regulation liberalizing state, Wisconsin (where voluntary unionism was also enacted), has just won the $10 billion first US plant to be built by China’s large electronics contractor Foxconn, edging out Ohio.

Becoming Less Competitive: Ontario’s Housing Regulation

Ontario’s competition threatening actions are not limited to business and labor policy. Land-use and housing policies are also making Ontario less competitive, first in the Toronto metropolitan area and now spreading across the province. About a decade ago, the province imposed its “Places to Grow” program that not one, but two urban containment boundaries. The highly publicized Greenbelt designates a huge swath of land on which development is not permitted.

Then there is the second urban containment boundary, the “settlement boundary,” which largely ensures that new development is limited to a far smaller area around the urbanization, further intensifying the price-escalating impact of the Greenbelt. In this crazy quilt of regulation, land owners operate in a sellers’ market, able to drive prices up for their scarce holdings, to the detriment of home buyers. This environment is particularly welcome to speculators. Consistent with the fundamentals of economics, urban containment boundaries lead to higher land prices where new housing is permitted, and higher house prices.

The procedures for supplying sufficient new greenfield development land require amendments of official community plans, a slow and cumbersome bureaucratic process. It is not surprising that Mattamy Homes Founder and CEO Peter Gilgin told Bloomberg that despite his largest homebuilding firm in the Toronto area having plenty of land for new houses, the necessary approvals are very difficult to obtain.

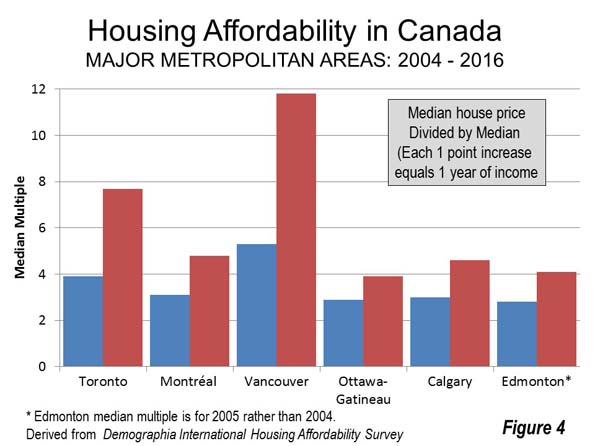

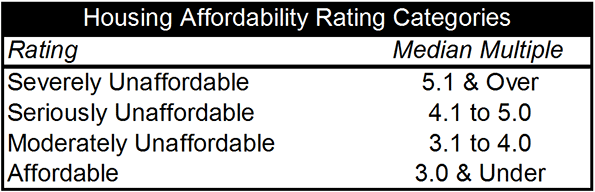

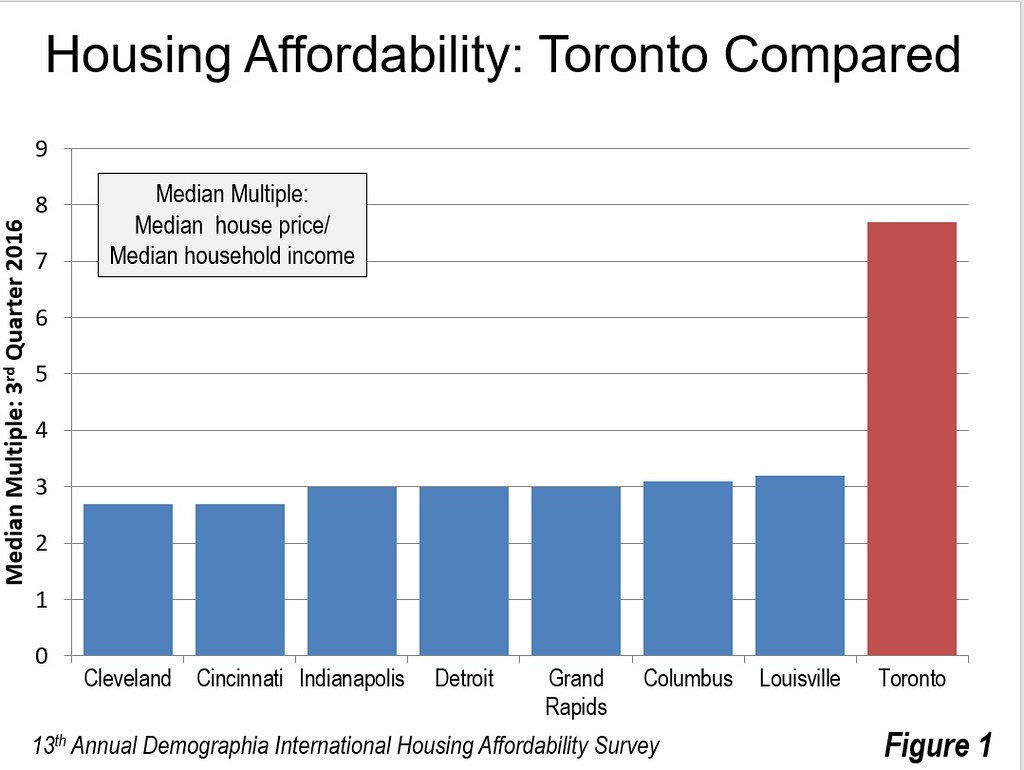

The effects on house prices have been dramatic. In 2004, Toronto’s median house price was 3.9 times its median household income (median multiple). At that point, it had actually been reduced from 4.3 in 1971 and had hovered around 3.5 in the intervening years. According to the 13th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, by 2016 house prices virtually doubled relative to incomes, with a median multiple of 7.7. This means a lower standard of living and greater relative poverty.

Meanwhile, the house price increases are spreading from Toronto to nearby metropolitan areas. For example, house prices in Kitchener – Waterloo, Canada’s “Silicon Valley” rose 40 percent in the single year ended April 2017. This is nearly double the rate of Toronto that over the same period.

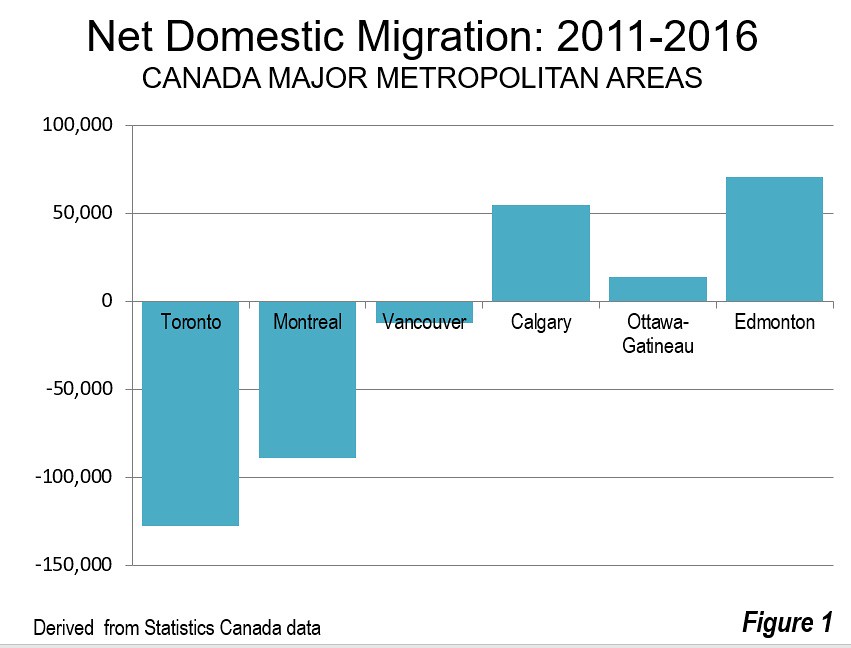

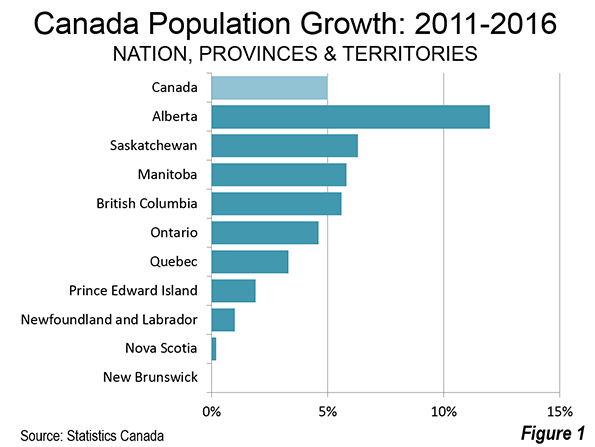

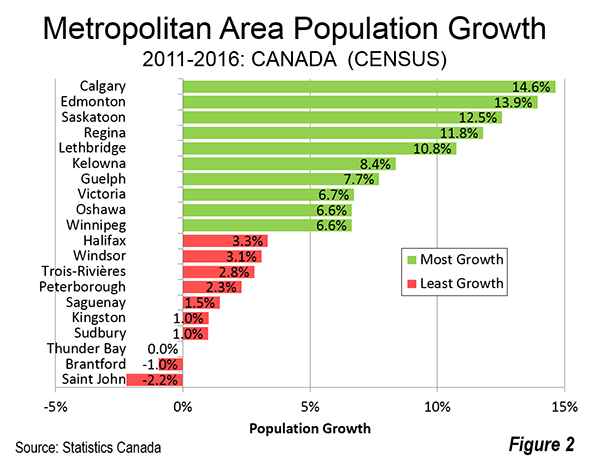

The most recent domestic migration data indicates that people are moving out of the Toronto metropolitan area in droves. Since the 2011 census, more than 125,000 more people have left the Toronto area for other parts of Ontario that have moved in. This is the same dynamic apparent in the United States, where differentials in housing affordability have been cited as a principal reason for domestic migration gains and losses, as households flee from higher cost to lower-cost areas.

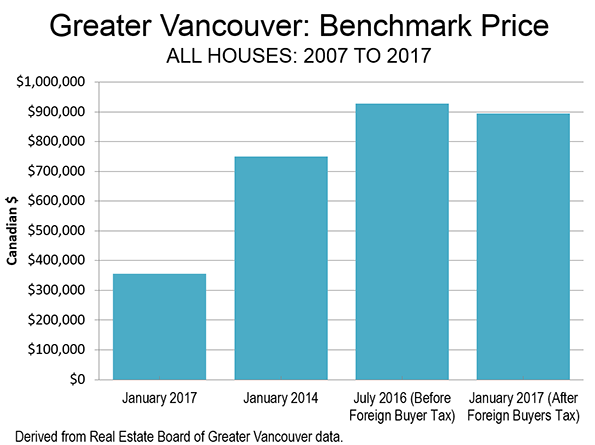

A recently imposed foreign buyers tax led to somewhat lower prices in the Toronto area last year, but they are still 6.3 percent above a year ago and rising at a rate three times that of average earnings. Without restoring the competitive market for land on the periphery, it is likely that house prices will continue rising relative to incomes, to the detriment, in particular, of younger households.

Meanwhile, house prices are substantially lower in US states nearby Ontario. As late as the mid-2000’s, there was little difference between the housing affordability across Ontario, including Toronto, and the Michigan, Ohio, Indiana and Kentucky. That is no longer the case.

Immigration laws, however, do not permit the free movement of labor across the Canadian-US border, so there is no likelihood that Ontarians will move to the United States for lower cost housing. But capital is far more mobile. Companies that develop new business locations, especially manufacturing, often locate where they can maximize returns for their shareholders. Moreover, companies establishing new facilities are also interested in their employees being able to live close enough to commute to the plant.

Figure 1 shows the metropolitan area housing affordability, measured by the median multiple, for Toronto, as well as major metropolitan areas in the four nearby states. Residents of Cleveland and Cincinnati pay nearly two-thirds less of their income for their houses than do residents of Toronto. In Indianapolis, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Columbus and Louisville, residents pay approximately 60 percent less for their houses than in Toronto. Meanwhile, no one should confuse the sometimes characterized as decrepit city of Detroit, reeling from decades of misgovernance, with its leafy suburbs, where 85 percent of the metropolitan area’s people live.

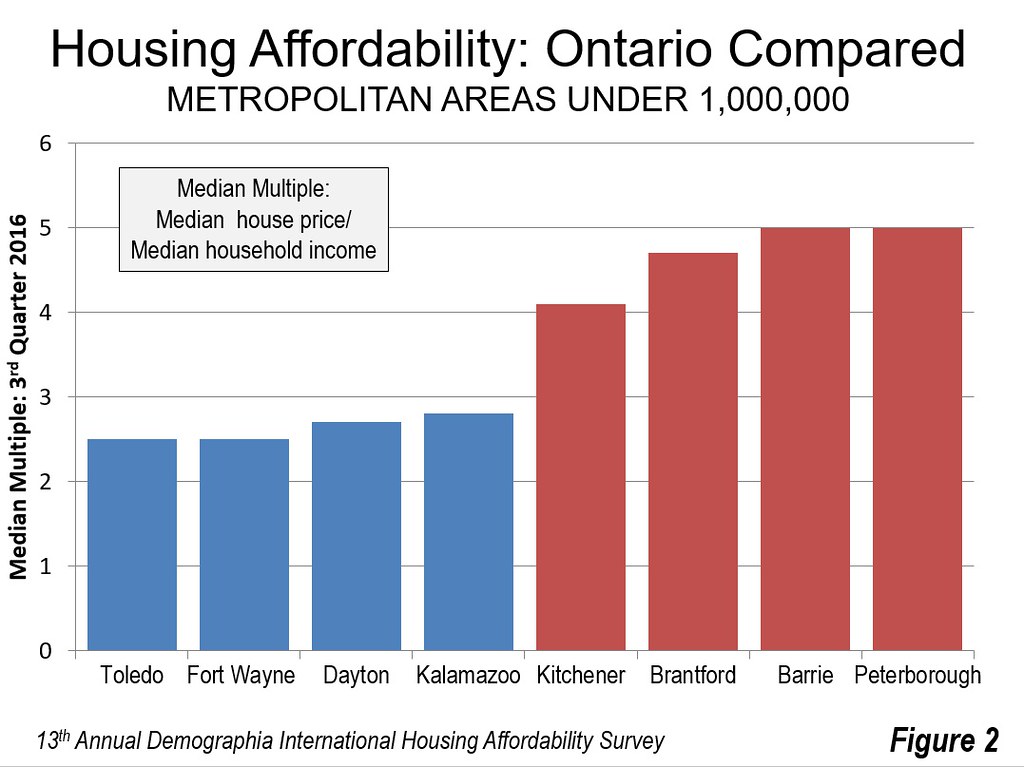

Figure 2 indicates that things are a bit better among other Greater Golden Horseshoe metropolitan areas. Residents pay from 4.7 to 5.0 times their incomes in Brantford, Barrie and Peterborough. This is still up to double the 2.5 times incomes that residents pay in Toledo (Ohio) and Fort Wayne (Indiana). House prices are slightly higher in Dayton and Kalamazoo, but still at least than 40 percent below the three Ontario metropolitan areas.

The Need for Competitive Policies

Maintaining economic growth and the standard of living is important to Ontario’s 14 million people. At the same time, the world is becoming more competitive. Ontario needs to be careful, or economic development departments from across the increasingly competitive states of the Midwest could reap a harvest in business investment and jobs.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Pearson International Airport (Mississauga, Brampton and Toronto), Canada’s Largest employment centre (by author)