What cities are best positioned to grow and prosper in the coming decade?

To determine the next boom towns in the U.S., with the help of Mark Schill at the Praxis Strategy Group, we took the 52 largest metro areas in the country (those with populations exceeding 1 million) and ranked them based on various data indicating past, present and future vitality.

We started with job growth, not only looking at performance over the past decade but also focusing on growth in the past two years, to account for the possible long-term effects of the Great Recession. That accounted for roughly one-third of the score. The other two-thirds were made up of a a broad range of demographic factors, all weighted equally. These included rates of family formation (percentage growth in children 5-17), growth in educated migration, population growth and, finally, a broad measurement of attractiveness to immigrants — as places to settle, make money and start businesses.

We focused on these demographic factors because college-educated migrants (who also tend to be under 30), new families and immigrants will be critical in shaping the future. Areas that are rapidly losing young families and low rates of migration among educated migrants are the American equivalents of rapidly aging countries like Japan; those with more sprightly demographics are akin to up and coming countries such as Vietnam.

Many of our top performers are not surprising. No. 1 Austin, Texas, and No. 2 Raleigh, N.C., have it all demographically: high rates of immigration and migration of educated workers and healthy increases in population and number of children. They are also economic superstars, with job-creation records among the best in the nation.

Perhaps less expected is the No. 3 ranking for Nashville, Tenn. The country music capital, with its low housing prices and pro-business environment, has experienced rapid growth in educated migrants, where it ranks an impressive fourth in terms of percentage growth. New ethnic groups, such as Latinos and Asians, have doubled in size over the past decade.

Two advantages Nashville and other rising Southern cities like No. 8 Charlotte, N.C., possess are a mild climate and smaller scale. Even with population growth, they do not suffer the persistent transportation bottlenecks that strangle the older growth hubs. At the same time, these cities are building the infrastructure — roads, cultural institutions and airports — critical to future growth. Charlotte’s bustling airport may never be as big as Atlanta’s Hartsfield, but it serves both major national and international routes.

Of course, Texas metropolitan areas feature prominently on our list of future boom towns, including No. 4 San Antonio, No. 5 Houston and No. 7 Dallas, which over the past years boasted the biggest jump in new jobs, over 83,000. Aided by relatively low housing prices and buoyant economies, these Lone Star cities have become major hubs for jobs and families.

And there’s more growth to come. With its strategically located airport, Dallas is emerging as the ideal place for corporate relocations. And Houston, with its burgeoning port and dominance of the world energy business, seems destined to become ever more influential in the coming decade. Both cities have emerged as major immigrant hubs, attracting on newcomers at a rate far higher than old immigrant hubs like Chicago, Boston and Seattle.

The three other regions in our top 10 represent radically different kinds of places. The Washington, D.C., area (No. 6) sprawls from the District of Columbia through parts of Virginia, Maryland and West Virginia. Its great competitive advantage lies in proximity to the federal government, which has helped it enjoy an almost shockingly ”good recession,” with continuing job growth, including in high-wage science- and technology-related fields, and an improving real estate market.

Our other two top ten, No. 9 Phoenix, Ariz., and No. 10 Orlando, Fla., have not done well in the recession, but both still have more jobs now than in 2000. Their demographics remain surprisingly robust. Despite some anti-immigrant agitation by local politicians, immigrants still seem to be flocking to both of these states. Known better s as retirement havens, their ranks of children and families have surged over the past decade. Warm weather, pro-business environments and, most critically, a large supply of affordable housing should allow these regions to grow, if not in the overheated fashion of the past, at rates both steadier and more sustainable.

Sadly, several of the nation’s premier economic regions sit toward the bottom of the list, notably former boom town Los Angeles (No. 47). Los Angeles’ once huge and vibrant industrial sector has shrunk rapidly, in large part the consequence of ever-tightening regulatory burdens. Its once magnetic appeal to educated migrants faded and families are fleeing from persistently high housing prices, poor educational choices and weak employment opportunities. Los Angeles lost over 180,000 children 5 to 17, the largest such drop in the nation.

Many of L.A.’s traditional rivals — such as Chicago (with which is tied at No. 47), New York City (No. 35) and San Francisco (No. 42) — also did poorly on our prospective list. To be sure, they will continue to reap the benefits of existing resources — financial institutions, universities and the presence of leading companies — but their future prospects will be limited by their generally sluggish job creation and aging demographics.

Of course, even the most exhaustive research cannot fully predict the future. A significant downsizing of the federal government, for example, would slow the D.C. region’s growth. A big fall in energy prices, or tough restrictions of carbon emissions, could hit the Texas cities, particularly Houston, hard. If housing prices stabilize in the Northeast or West Coast, less people will flock to places like Phoenix, Orlando or even Indianapolis (No.11) , Salt Lake City (No. 12) and Columbus (No. 13). One or more of our now lower ranked locales, like Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York, might also decide to reform in order to become more attractive to small businesses and middle class families.

What is clear is that well-established patterns of job creation and vital demographics will drive future regional growth, not only in the next year, but over the coming decade. People create economies and they tend to vote with their feet when they choose to locate their families as well as their businesses. This will prove more decisive in shaping future growth than the hip imagery and big city-oriented PR flackery that dominate media coverage of America’s changing regions.

| Cities of the Future Rankings | |

| Rank | Metropolitan Area |

| 1 | Austin, TX |

| 2 | Raleigh, NC |

| 3 | Nashville, TN |

| 4 | San Antonio, TX |

| 5 | Houston, TX |

| 6 | Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV |

| 7 | Dallas-Fort Worth, TX |

| 8 | Charlotte, NC-SC |

| 8 | Phoenix, AZ |

| 10 | Orlando, FL |

| 11 | Indianapolis, IN |

| 12 | Salt Lake City, UT |

| 13 | Columbus, OH |

| 14 | Jacksonville, FL |

| 15 | Atlanta, GA |

| 16 | Las Vegas, NV |

| 16 | Riverside, CA |

| 18 | Portland, OR-WA |

| 19 | Denver, CO |

| 20 | Oklahoma City, OK |

| 21 | Baltimore, MD |

| 22 | Louisville, KY-IN |

| 22 | Richmond, VA |

| 24 | Seattle, WA |

| 25 | Kansas City, MO-KS |

| 26 | San Diego, CA |

| 27 | Miami, FL |

| 28 | Tampa, FL |

| 29 | Sacramento, CA |

| 30 | Birmingham, AL |

| 31 | New Orleans, LA |

| 32 | Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

| 33 | Minneapolis, MN-WI |

| 34 | St. Louis, MO-IL |

| 35 | Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN |

| 35 | New York, NY-NJ-PA |

| 37 | Boston, MA-NH |

| 38 | Memphis, TN-MS-AR |

| 39 | Pittsburgh, PA |

| 40 | Virginia Beach, VA-NC |

| 41 | Rochester, NY |

| 42 | Buffalo, NY |

| 42 | San Francisco, CA |

| 44 | Hartford, CT |

| 45 | Milwaukee, WI |

| 45 | San Jose, CA |

| 47 | Chicago, IL-IN-WI |

| 47 | Los Angeles, CA |

| 49 | Providence, RI-MA |

| 50 | Detroit, MI |

| 51 | Cleveland, OH |

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.

Photo by Exothermic Photography

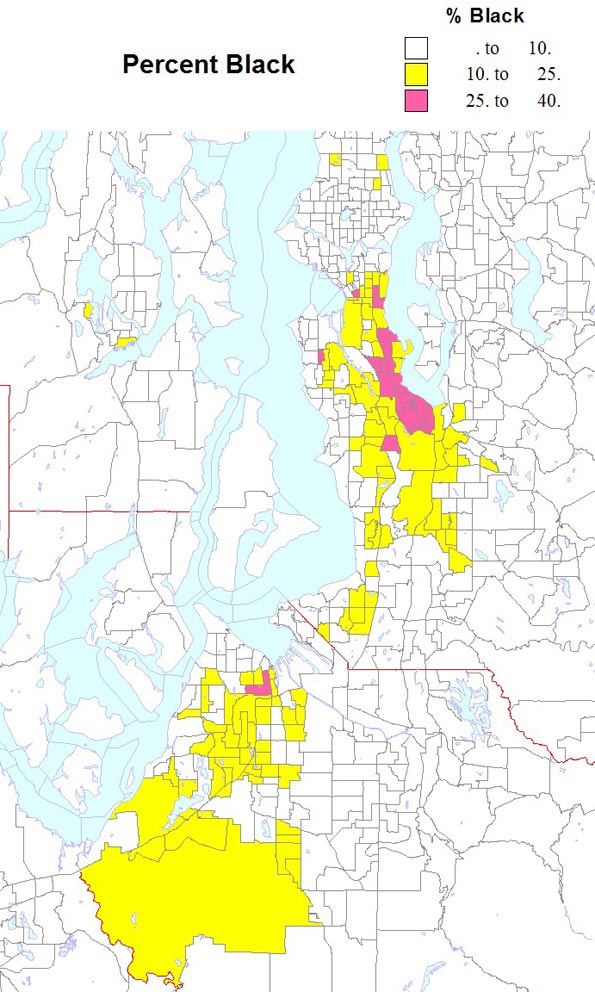

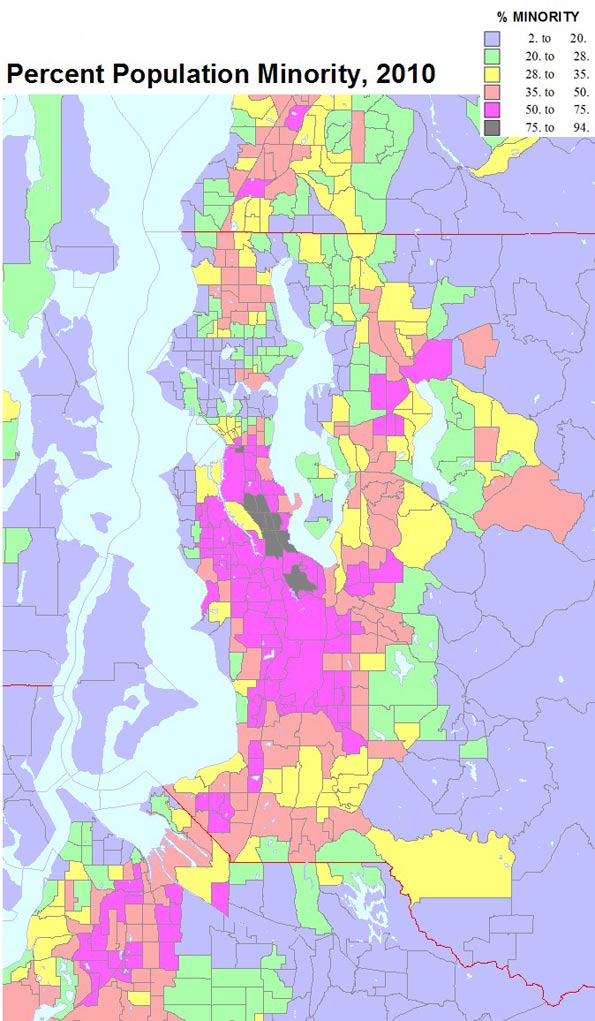

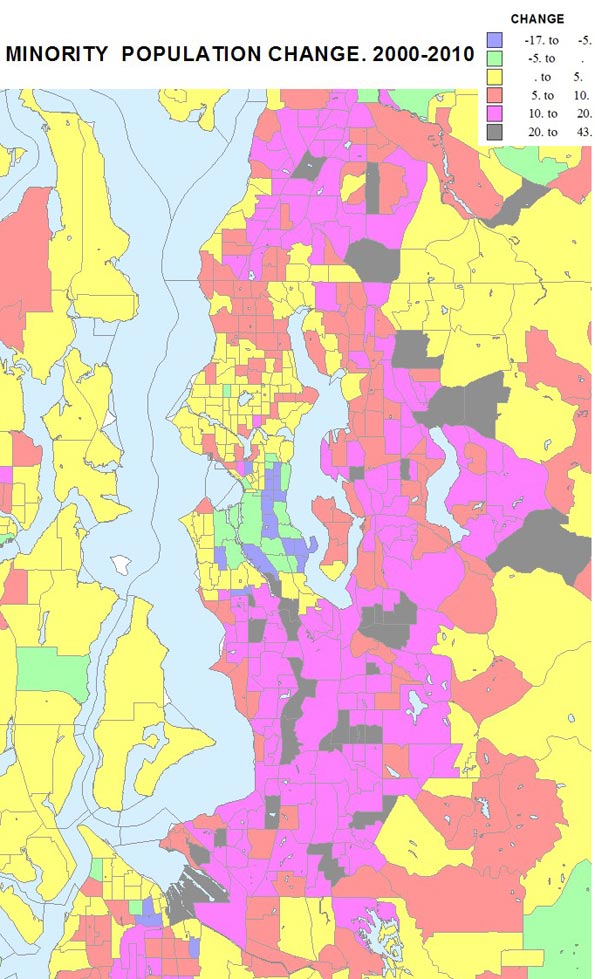

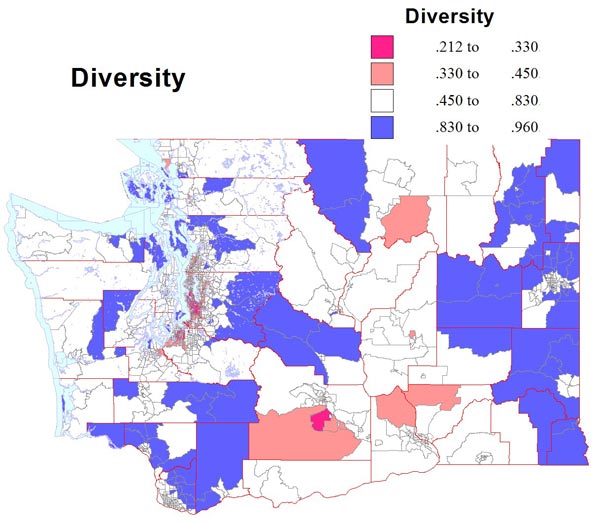

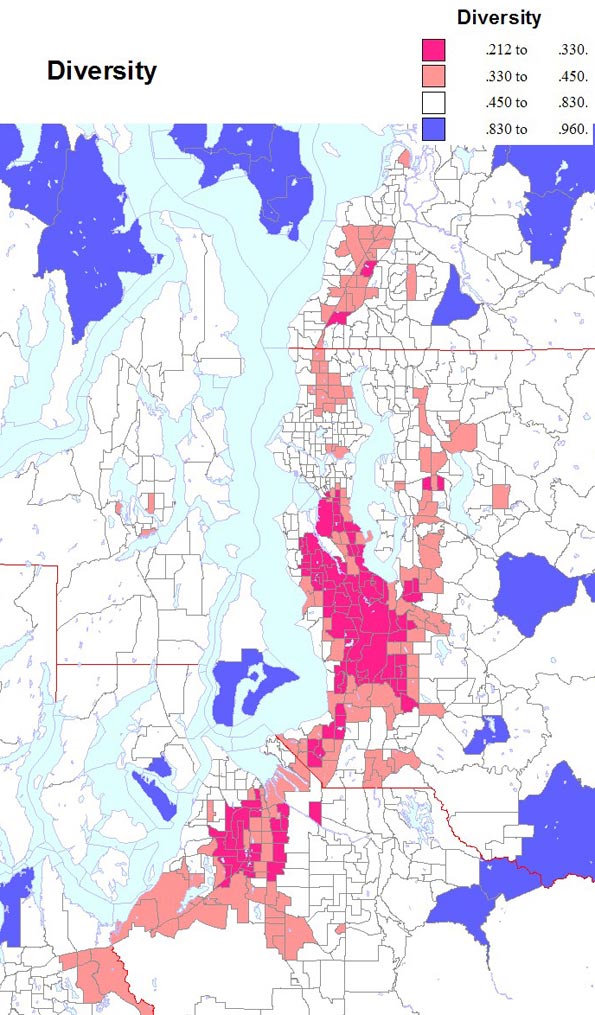

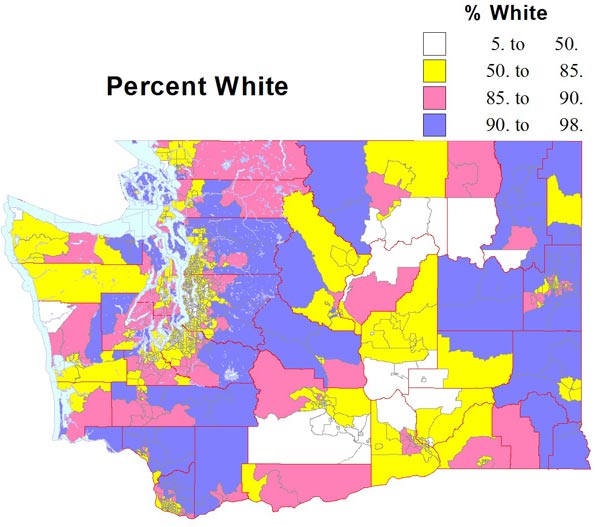

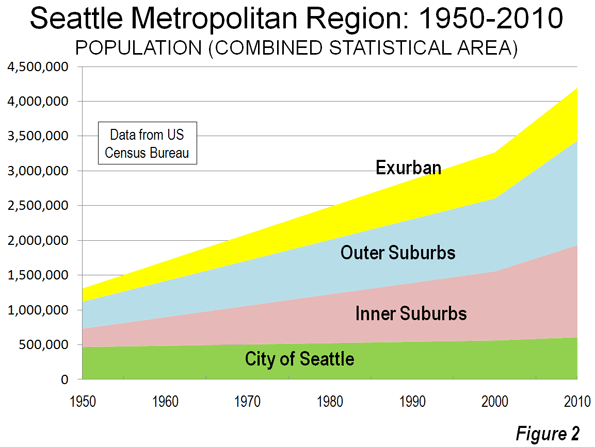

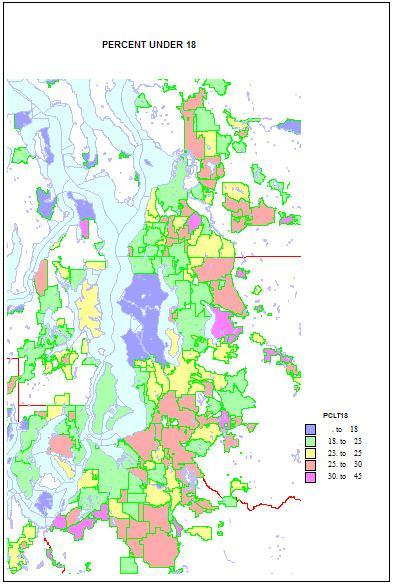

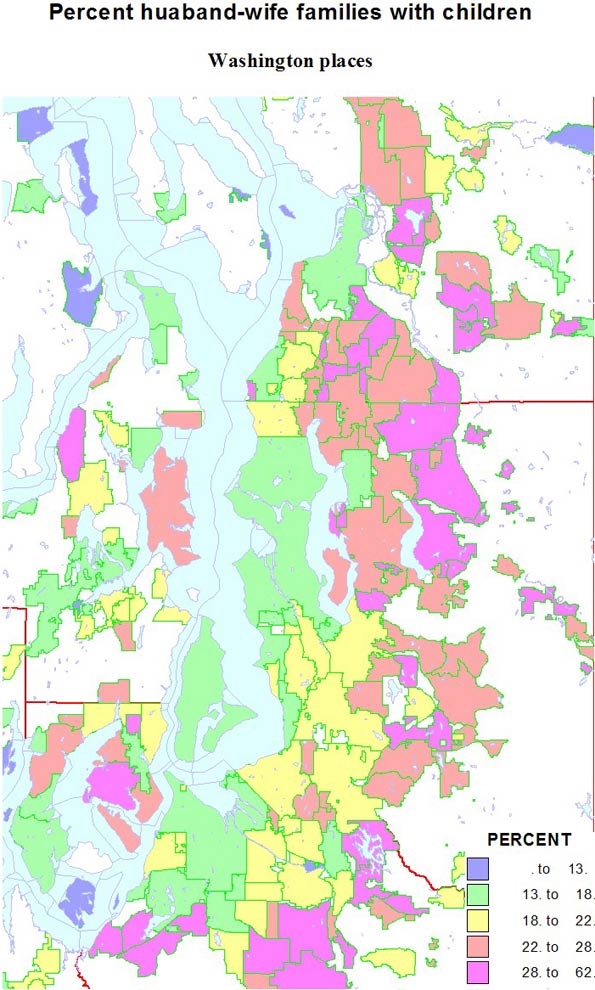

Higher shares of persons under 5 reveal areas of young families. The highest shares are in military bases and Latino towns in eastern Washington, but are quite high, over 12 percent, in the farthest suburban and exurban places around Seattle such as Duvall and Snoqualmie. They are lowest in retirement towns, on islands such as Vashon and Bainbridge, and in some college towns such as Pullman.

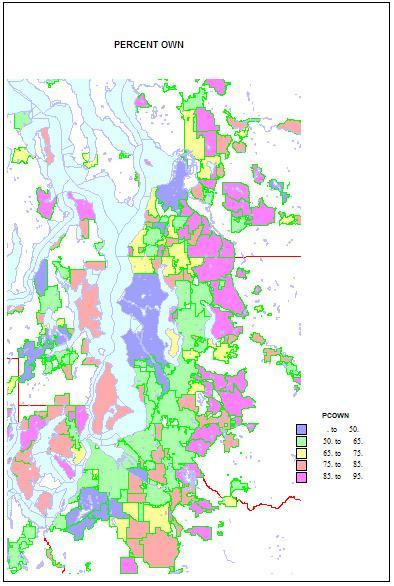

Higher shares of persons under 5 reveal areas of young families. The highest shares are in military bases and Latino towns in eastern Washington, but are quite high, over 12 percent, in the farthest suburban and exurban places around Seattle such as Duvall and Snoqualmie. They are lowest in retirement towns, on islands such as Vashon and Bainbridge, and in some college towns such as Pullman. Home ownership is related to both age and household types. Rates of home ownership are extremely high, in the 90s in newer and more affluent suburbs, with mainly single family homes; the rates are lowest on military bases, college towns, and in a few less affluent suburbs, such as Tukwila. As for the city of Seattle — which has indeed changed its character in a fundamental way — home ownership has dropped to a low of 48 percent. This shift helps us understand the cleavages in Seattle’s body politic, as a formerly very middle class city adjusts to an influx of singles, renters, and young people.

Home ownership is related to both age and household types. Rates of home ownership are extremely high, in the 90s in newer and more affluent suburbs, with mainly single family homes; the rates are lowest on military bases, college towns, and in a few less affluent suburbs, such as Tukwila. As for the city of Seattle — which has indeed changed its character in a fundamental way — home ownership has dropped to a low of 48 percent. This shift helps us understand the cleavages in Seattle’s body politic, as a formerly very middle class city adjusts to an influx of singles, renters, and young people.

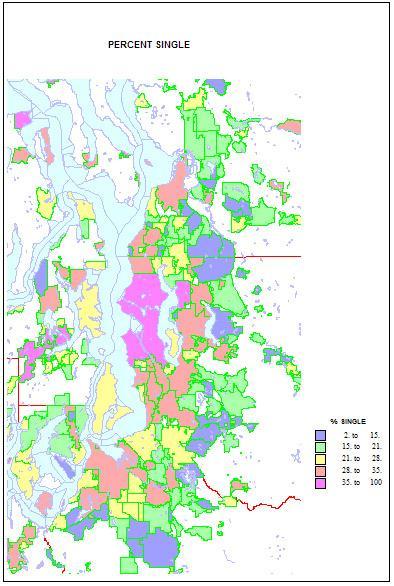

Conversely, singles are highest in two island towns, Friday Harbor and Langley, but Seattle is an extremely high 41 percent. Shares are lowest in the same new suburbs rich in families, as in Sammamish, at 11 percent. Shares of unmarried partners are a high 10 percent of households in Seattle, but are higher on Indian reservations and the cities of Hoquiam and Aberdeen. The share of single-parent households is also high on Indian reservations, in less affluent and more ethnic suburbs like Parkland and Bryn Mawr and Tukwila. It is lowest in the newer, family-filled far suburbs.

Conversely, singles are highest in two island towns, Friday Harbor and Langley, but Seattle is an extremely high 41 percent. Shares are lowest in the same new suburbs rich in families, as in Sammamish, at 11 percent. Shares of unmarried partners are a high 10 percent of households in Seattle, but are higher on Indian reservations and the cities of Hoquiam and Aberdeen. The share of single-parent households is also high on Indian reservations, in less affluent and more ethnic suburbs like Parkland and Bryn Mawr and Tukwila. It is lowest in the newer, family-filled far suburbs.