With the release of results for over 20 states, the 2010 Census has provided some strong indicators as to the real evolution of the country’s demography. In short, they reveal that Americans are continuing to disperse, becoming more ethnically diverse and leaning toward to what might be called “opportunity” regions.

Below is a summary of the most significant findings to date, followed by an assessment of what this all might mean for the coming decade.

Point One: America is becoming more suburban.

For much of the past decade, there has been a constant media drumbeat about the “return to the cities.” Urban real estate interests, environmentalists and planners have widely promoted this idea, and it has been central to the ideology of the Obama administration, the most big-city dominated in at least a half century. “We’ve reached the limits of suburban development,” Housing Secretary Shaun Donovan opined last February, “People are beginning to vote with their feet and come back to the central cities.”

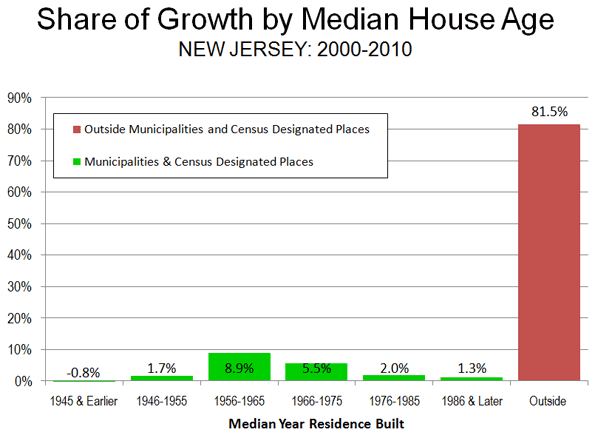

Donavan and others cite such things as the energy price spike in the mid-aughts as well as the mortgage crisis as contributing to the “back to the city” trend. Yet in reality the actual numbers suggest that Donavan and his cronies may need a serious reality check. The Census reveals that, contrary to the “back to the city” rhetoric, suburban growth continues to dominate in most regions of the country, constituting between 80% and 100% of all growth in all but three of the 16 metropolitan areas reporting.

This includes sprawling regions like Houston, “smart growth“ areas like Seattle and Portland (where suburbs accounted for more than 80% of all growth over the decade) and Midwestern regions like St. Louis, which like Chicago saw a sharp decline in the urban population. The only exceptions have been Oklahoma City, Austin or San Antonio, with vast expanses still allowing for much of new development to take place within the city limits.

To be sure, no one should pretend that urban fortunes have sunk to their 1970s nadir. Yet overall, central cities, which accounted for a 11% of metropolitan growth in the 1990s, constituted barely 4% of the growth in the last decade. Some core cities, notably Chicago, have shrunk after making gains in the ’90s. Indeed Chicago — the president’s adopted hometown and the poster child of the urban “comeback” — took what analyst Aaron Renn humorously dubbed “a Census shellacking,” losing some 200,000 people, while the outer suburban ring continued to grow and diversify their populations. The Windy City’s population is now down to the lowest level since the 1910 Census.

Point Two: America is becoming more diverse, and the diversity is spreading.

The racial reordering of America is proceeding apace. Nowhere is this more clear than in Texas, where Hispanic and Asian populations have driven much of the state’s demographic growth. Latinos alone now account for roughly 38% of all Texans. Immigration rates in Dallas and Houston are now higher than for Chicago, Washington, Seattle and Atlanta. Texas, notes long-time observer Candace Evans, is becoming the country’s premier laboratory for promoting a successful diversity.

There are other major shifts in ethnic demographics. For one thing, minorities continue to head to the suburban rings around most major cities. African-Americans and even Latinos may be fleeing places like Chicago, but they continue to move in large numbers to suburban locales in surrounding Illinois counties. , especially south of the city. Others appear to have headed to places like the traditional black-opportunity magnet of Atlanta and or other southern hubs, such as Nashville.

Another trend appears to be the migration of ethnic minorities to areas that, in the past, have been primarily white. This is clear in the thriving Indianapolis area, where the African-American population grew by 28% and the Hispanic population by 161%, or some 56,000 souls. Look for more minority growth in such areas which have the advantage of affordable housing, robust economies and better than average job growth.

3. The Shift to “Opportunity Regions”

As the economy slid in the last years of the decade, population growth slowed, particularly in some Sun Belt states, such as Florida and Nevada, that thrived during the bubble. In contrast newcomers flocked to places, notably in the Texas cities, that offered better prospects. Austin, San Antonio, Houston and Dallas-Ft. Worth regions all grew by 20% or more over the decade.

The key here seems to be affordability and jobs. As economist Mark Sharpe has illustrated, Texas private sector job growth last year was 2.7%, compared with 1% nationally. Unfortunately, unemployment remains over 8%, since of this growth was absorbed by newcomers. In contrast, places with the slowest, or negative growth, tend also to be losing jobs. For example, although the residential population of Chicago’s loop tripled in the past decade to 20,000,the famed business district lost almost 65,000 jobs.

But it’s not just Sun Belt cities that are gaining on places like Chicago. Indianapolis has emerged as a different kind of “opportunity region.” It lacks the dynamism and diversity of the Texas cities, but it has continued to attract people from all over the country, including the surrounding rural or old Rust Belt parts of the state. Overall the Indianapolis region grew nearly 15% over the decade, roughly 50% higher than the national average, as much as Portland and more than Seattle.

In contrast, growth seems to be slowing in some formerly hot areas. Population increases for Seattle, Portland and Denver were around 14%, about half the rate of the previous decade. Part of this may have to do with high unemployment, particularly in Oregon, and high housing prices. Still, these three areas continue to grow much faster than regions such as Chicago, St. Louis or Baltimore where growth struggled in the single digits

Possible Long-term Implications

These shifts suggest that the Obama administration might want to rethink its high-density and urban-oriented strategy. Despite all the media focus on an imagined “back to the city” movement, Americans continue to disperse to “opportunity regions” and toward the suburbs. As a result, expect generally conservative-leaning suburbs and exurbs to gain more power after reapportionment and core city influence to decline further.

Yet the Census numbers also have some unsettling aspects for Republicans. The increasing minority population even in heartland states such as Indiana, not to mention Texas, could undermine GOP gains, particularly if the party listens to its strong nativist wing. Diversification in the suburbs could ultimately turn some of these areas to the center or even left.

The new American generation arising in the census will be increasingly diverse. A growing portion will consist of the children of immigrants, and they will be predominately English-speaking. This suggests a more active and engaged minority population, perhaps susceptible to a pro-growth GOP message and the economy of “opportunity regions” but likely hostile to overtly anti-immigrants posturing.

Whatever your politics or economic interests, the Census suggests that the country is changing in dramatic way– if not always in the ways often predicted by pundits, planners or the media. It usually makes more sense to study the actual numbers, than follow the wishful thinking of largely urban-centric, big-city-based and often quite biased analysts.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History . His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050 , released in February, 2010.

, released in February, 2010.

Indianapolis Photo by IndySawmill

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library