Media coverage of America’s best jobs usually focuses on blue-collar sectors, like manufacturing, or elite ones, such as finance or technology. But if you’re seeking high-wage employment, your best bet lies in the massive “business and professional services” sector.

This unsung division of the economy is basically a mirror of any and all productive industry. It includes everything from human resources and administration to technical and scientific positions, as well as accounting, legal and architectural firms.

Overall there are roughly 17 million professional and business services jobs, 4 million more than manufacturing. This makes it twice as big as the finance sector and five times the size of the much-ballyhooed tech sector. While its average salary – roughly $55,000 a year – is somewhat lower than in those other elite sectors, its wages are still higher than those in all the other large sectors, like health. The sector’s $1 trillion in total pay per year accounts for nearly 20% of all wages paid in the nation; finance and tech together only account for $812 billion.

More than that, the business and professional services sector has encompassed the fastest-growing part of the high-wage economy. Employment in lower-wage sectors like education has also grown quickly. But employment in other sectors that pay their employees well, such as technology, has remained stagnant; jobs in some, such as manufacturing, have fallen sharply. Critically, the business services sector – particularly at the better-paying end – seems to have weathered the current recession better than these other high-wage sectors.

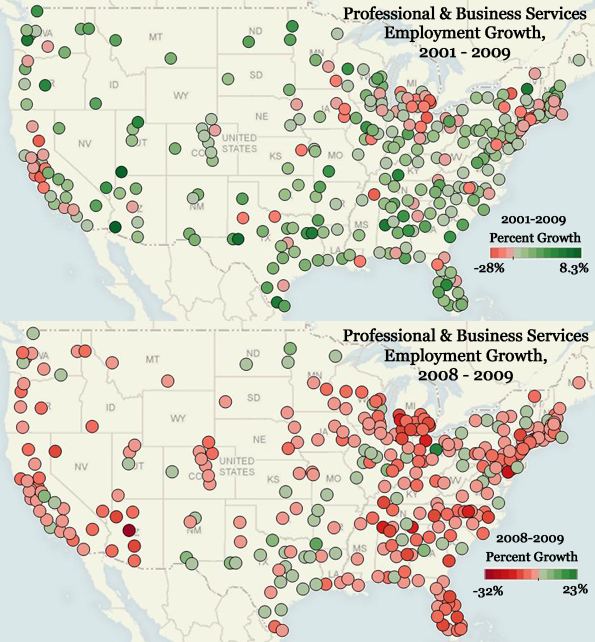

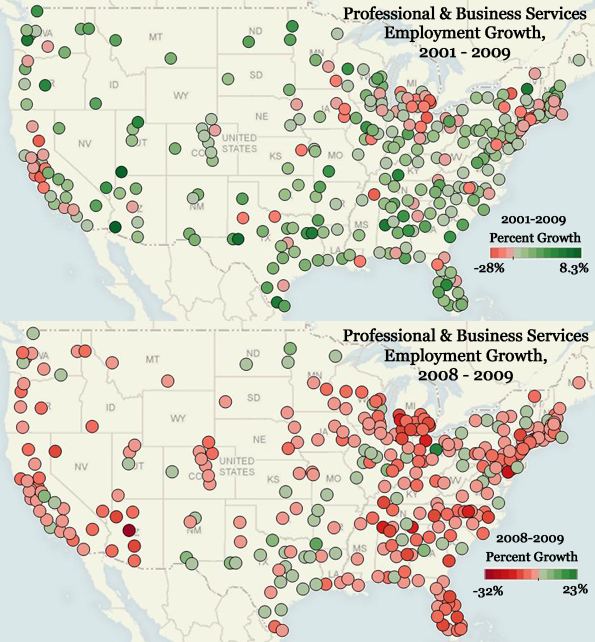

The crucial question remains: In what regions is this critical economic cog booming? In a new analysis with my colleagues at the Praxis Strategy Group, we examined Bureau of Labor Statistics employment data for this sector, keeping an eye on trends over both the last year and the last decade. Some of the metropolitan areas that boasted short-term growth in this sector also maintained steady employment success over the long-term, which suggests that these particular cities have sturdy economies that aren’t as prone to intense boom-bust cycles.

At the top of our list of best places is greater Washington, D.C., and its surrounding suburbs in Virginia and Maryland. Government jobs may drive that economy, but it is the lawyers, consultants and technical services firms who harvest the richest benefits. As New York University public policy professor Mitchell Moss observes, Washington has emerged as the “real winner” in the recession – not just for public-sector workers but private-sector ones too.

| Fastest Growing Professional and Business Services Sectors |

| Area Name |

Jobs in Sector 2009

(thousands) |

Sector Share of Jobs 2009

(percent of total) |

Growth 2008 – 2009

(percent growth) |

Cumulative Growth 2001 – 2009

(percent growth) |

2001-2009 Job Change (thousands) |

2008-2009 Job Change (thousands) |

| Northern Virginia, VA |

355.2 |

27.2% |

1.5% |

22.4% |

65.0 |

5.2 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV |

558.7 |

23.0% |

0.9% |

22.8% |

103.6 |

5.1 |

| Austin-Round Rock, TX |

112.4 |

14.4% |

3.3% |

18.7% |

17.7 |

3.6 |

| Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX |

382.3 |

14.7% |

0.9% |

19.2% |

61.5 |

3.2 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC |

106.6 |

14.0% |

2.8% |

8.0% |

7.9 |

2.9 |

| Bethesda-Frederick-Rockville, MD |

125.7 |

21.9% |

2.1% |

9.0% |

10.4 |

2.6 |

| Wichita, KS |

31.5 |

10.1% |

3.5% |

16.4% |

4.4 |

1.1 |

| Chattanooga, TN-GA |

25.9 |

10.6% |

4.3% |

11.8% |

2.7 |

1.1 |

| Peoria, IL |

23.0 |

12.1% |

4.5% |

43.2% |

6.9 |

1.0 |

| Rochester, NY |

61.8 |

11.9% |

1.5% |

1.9% |

1.1 |

0.9 |

| Augusta-Richmond County, GA-SC |

31.0 |

14.5% |

3.0% |

7.5% |

2.2 |

0.9 |

| Mansfield, OH |

5.1 |

9.1% |

19.4% |

4.1% |

0.2 |

0.8 |

| Kennewick-Pasco-Richland, WA |

20.8 |

22.2% |

4.2% |

20.2% |

3.5 |

0.8 |

| St. Louis, MO-IL |

195.4 |

14.6% |

0.4% |

3.9% |

7.4 |

0.8 |

| Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers, AR-MO |

33.5 |

16.2% |

2.2% |

34.2% |

8.5 |

0.7 |

| Macon, GA |

12.1 |

11.9% |

5.5% |

31.2% |

2.9 |

0.6 |

| Pittsburgh, PA |

158.9 |

13.9% |

0.4% |

14.5% |

20.1 |

0.6 |

| Fresno, CA |

30.7 |

10.3% |

1.9% |

23.3% |

5.8 |

0.6 |

| Provo-Orem, UT |

23.3 |

12.4% |

2.5% |

16.7% |

3.3 |

0.6 |

| Charleston-North Charleston-Summerville, SC |

42.2 |

14.3% |

1.3% |

31.1% |

10.0 |

0.5 |

Over the past year, parts of northern Virginia – ground zero for the so-called “beltway bandits” who work in industries the government depends on to do its job – have enjoyed the fastest growth in business and professional services, adding over 5,200 jobs despite the current downturn.

Other areas around the nation’s capital have also seen strong growth. The Washington D.C.-Arlington-Alexandria area, for example, came in second on our list, gaining nearly 5,100 positions, while No. 6 the Bethesda-Frederick-Rockville, Md., metro area added 2,600. In addition, yet another Virginia area – No. 5-ranked Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, a center for military-related industries – gained nearly 2,900 jobs in this sector.

It’s far too early to thank the free-spending ways of Barack Obama’s administration for all this growth. As anyone can tell you, the Bush White House and its Republican Congress were not exactly models of fiscal restraint. Plus, Washington and Northern Virginia have seen growth in their business services sectors over the last several years, in the period stretching from 2001 to 2009. Together those two metros added over 165,000 new jobs in this critical, high-wage sector.

Of course, you don’t have to head to Washington to find a high-paying job – although you might not be able to escape unpleasant summer weather. The other major group of business-services hot spots includes Austin, Texas, at No. 3, and Houston, at No. 4. These Lone Star local economies have continued to thrive not only during the current recession but also over the last decade.

The others winners include farther-afield locales in Kansas, Tennessee, Illinois and New York. These areas could be gaining both from companies seeking to lower costs and from the new capabilities for remote work due to the Internet. Even though they didn’t make our list, a host of smaller communities – like Mansfield, Ohio; Provo, Utah; and Charleston, S.C. – also enjoyed significant growth in the business services sector over the past year.

So if these are the places where this segment of the economy is growing and high-paying jobs are easier to come by, where is the opposite true? The worst cities on our list span three archetypes: Rust Belt basket cases, Sunbelt flame-outs and expensive big cities. Perhaps the toughest losses were in Michigan: Detroit and the Warren-Troy metro area suffered big setbacks both in the last year and over the last decade.

| Fastest Declining Professional and Business Services Sectors |

| Area Name |

Jobs in Sector 2009

(thousands) |

Sector Share of Jobs 2009

(percent of total) |

Growth 2008 – 2009

(percent growth) |

Cumulative Growth 2001 – 2009

(percent growth) |

2001-2009 Job Change (thousands) |

2008-2009 Job Change (thousands) |

| Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ |

289.2 |

16.0% |

-10.8% |

7.9% |

21.2 |

-35.1 |

| Warren-Troy-Farmington Hills, MI |

202.5 |

18.5% |

-12.0% |

-21.2% |

-54.4 |

-27.7 |

| Chicago-Naperville-Joliet, IL |

633.6 |

16.8% |

-4.1% |

-2.9% |

-19.0 |

-27.0 |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Glendale, CA |

574.7 |

14.3% |

-4.2% |

-3.4% |

-20.4 |

-25.2 |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA |

390.3 |

16.4% |

-5.9% |

-1.3% |

-5.1 |

-24.4 |

| Orlando-Kissimmee, FL |

170.9 |

16.2% |

-8.5% |

7.7% |

12.3 |

-16.0 |

| Santa Ana-Anaheim-Irvine, CA |

261.9 |

18.0% |

-4.7% |

4.0% |

10.2 |

-12.8 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI |

253.4 |

14.4% |

-4.6% |

-4.6% |

-12.2 |

-12.3 |

| Edison-New Brunswick, NJ |

164.5 |

16.3% |

-6.7% |

-2.6% |

-4.4 |

-11.9 |

| Detroit-Livonia-Dearborn, MI |

108.9 |

14.7% |

-9.5% |

-20.9% |

-28.8 |

-11.4 |

| Indianapolis-Carmel, IN |

120.3 |

13.4% |

-8.3% |

13.6% |

14.4 |

-10.8 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA |

133.7 |

11.2% |

-6.5% |

36.0% |

35.4 |

-9.2 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL |

223.2 |

18.5% |

-3.7% |

12.3% |

24.5 |

-8.6 |

| New York City, NY |

595.7 |

15.8% |

-1.4% |

-0.8% |

-5.1 |

-8.4 |

| Newark-Union, NJ-PA |

163.5 |

16.0% |

-4.7% |

-0.5% |

-0.8 |

-8.0 |

| Bergen-Hudson-Passaic, NJ |

130.6 |

14.6% |

-5.8% |

-9.1% |

-13.0 |

-8.0 |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI |

107.6 |

12.9% |

-6.6% |

-1.7% |

-1.8 |

-7.6 |

| Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall, FL |

139.1 |

13.4% |

-4.7% |

2.2% |

3.0 |

-6.8 |

| Oakland-Fremont-Hayward, CA |

158.0 |

15.6% |

-4.0% |

-7.1% |

-12.2 |

-6.7 |

| Las Vegas-Paradise, NV |

108.2 |

12.1% |

-5.8% |

38.1% |

29.9 |

-6.6 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA |

308.8 |

18.2% |

-2.0% |

-6.8% |

-22.5 |

-6.4 |

| Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA |

106.1 |

12.3% |

-5.6% |

-1.8% |

-1.9 |

-6.3 |

| Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH |

137.8 |

13.3% |

-4.3% |

-5.2% |

-7.6 |

-6.1 |

| Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO |

207.0 |

16.9% |

-2.9% |

4.0% |

8.0 |

-6.1 |

Consistent job losses in business services in these areas – some 54,000 in the Troy area since 2001 – reveal the clear connection between employment in business services and in the region’s fundamental auto industry. It turns out that elite services often prove dependent on basic industry. When industrial plants shut down, it’s not just blue-collar workers and company executives that suffer; as a result, these firms will use fewer lawyers, accountants, architects and technical consultants.

A similar picture emerges in cities like Phoenix, which lost about 35,000 business-services jobs in just one year. This loss stems from the collapse of the housing bubble, which powered the rest of the regional economy. The same meltdown caused smaller but still significant reversals in one-time boomtowns like Orlando, Fla., Atlanta and Southern California’s Santa Ana region, which encompasses Orange County, where business service employment dropped by double-digit rates over the past year.

Yet these same areas should see some recovery, perhaps more so than the traditional auto manufacturing-focused towns. Phoenix, Orlando and other Sun Belt locations – including a host of other areas in Florida – all saw increasing employment in business services over the past decade. If the economy comes back, along with a stabilization of the residential real estate market, business-services job growth will likely begin to take off again. After all, the fundamental reasons for the success of these areas, such as warm weather, lower costs and the need to serve a growing population, have not fundamentally changed.

Perhaps most perplexing is the fate of some of the other places on our worst cities list, particularly the biggest metropolitan areas. The professional and business services sector is widely considered ideal for large, cosmopolitan centers, since lots of industries require support. But Chicago experienced a huge chunk of job losses – almost 25% – in this sector during the last year. Other big cities, including Los Angeles, Minneapolis and New York, also suffered.

This is not a new phenomenon. These and other big cities, like Boston and San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland in California, have been shedding these types of jobs since 2001. These losses, however, have been concentrated at the lower-wage end of the business service pyramid, in areas like human resources and administration. These are the positions that companies can fill more easily and cheaply using the Internet or by hiring in less expensive outposts.

That’s why Washington and its environs, which has seen across-the-board business growth, remain the great exception. Many business-services jobs outside the beltway appear to be becoming more nomadic, based in places where firms face lower costs and where workers can afford to live well on middle-income salaries. Even the long-term resiliency of higher-wage employment like law and accounting in traditional business hubs like New York could be at risk over time, with some jobs shifting to less expensive locales or even overseas.

The changing nature of business services presents a boon to some communities and a challenge to others as they seek to survive and thrive in spite of the current recession. How some cities manage to grow this segment of their economies may well presage which parts of the country will thrive best during the years of recovery – and beyond.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History . His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin early next year.

. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin early next year.