I’ve said before that I don’t think Chicago is well positioned to become some type of dominant tech hub, but should only seek to get its “fair share” of tech. However, as the third largest city in America, Chicago’s fair share on tech is still pretty darn big. If you look at what’s been happening in the city the last couple of years, I think you’d have to have to say it’s something real. Built in Chicago lists 1145 companies in its inventory, and that’s definitely something. I’ll give a bit of a mea culpa by admitting that the tech community has done better than I probably thought it would a couple years ago, though I still stand behind the statement I made at the beginning of the paragraph.

Part of what has happened in Chicago is the general decentralization of technology in America. It used to be that tech in America was heavily concentrated in the Bay Area and Boston. In an era when pretty much literally anybody can start a company, you simply don’t need to be in any particular place to be successful these days.

Mark Suster made this point in his Tech Crunch post, 12 Tips To Building A Successful Startup Community Where You Live:

I would point out that these days there are really talented tech developers and teams everywhere. And I really mean everywhere. Ever play Zynga’s “Words with Friends” or any of their “with Friends” games? Didn’t come out of the SF facility. It came from an amazing small startup in McKinney, Texas (30 miles North of Dallas) called NewToy, which they acquired.

Think the next big startup can’t come from Dallas? Think again. Angry Birds? From startup Rovio in Finland.

Think USV is only invested around Union Square in NYC? How about in the last 12 months deals were announced with Dwolla (Iowa) and Pollenware (Kansas City). I met the Pollenware team myself – they were KILLER.

In this environment, it’s possible for lots of cities to find success. This is why places like New York and Chicago have been table to reboot their tech ambitions, and why some of those hot startups Suster mentioned are in smaller Midwest cities. Strong tech/startup scenes have been emerging all over the country. Being a startup hub isn’t what it used to be in terms of joining a highly exclusive club.

This is a case where there aren’t of necessity winners and losers. It isn’t like the Midwest can have just one tech center, for example, and thus the battle for Chicago is to be the winner, while everyone else gets to be a loser. The good news here is that Chicago can win and other places can win too. This might be one economic change that really can start rebranding a region.

Not only has there been legitimate strength in the Chicago tech community of late, it is also starting to get some good press. For example, just this week the New York Times ran a story on tech businesses moving into the Merchandise Mart. (An unfortunate subtext of this piece appears to be a serious decline in Chicago’s vaunted design community, however). This is one of a number of positive pieces that have appeared recently.

The city has really put on the full court press for tech, with Mayor Rahm Emanuel in effect making it the signature economic development cluster of his administration. I cannot think of any other sector of the economy in which Emanuel has so put his personal imprimatur. He has repeatedly stood up to endorse Chicago tech and its ambitions, and I think it’s fair to say he’s got a lot riding on it being successful – and not just successful, but an outsized success compared to peer cities.

Rahm has also put city action behind the marketing. For example, making an open data push, and also the recent broadband deployment initiative to underserved areas.

The trendlines certainly appear positive for Chicago at this point, but I want to highlight a few areas I find lacking and/or risky to the future.

The Booster Club Society

I’ll lead off a video from last year’s Chicago Ideas Week. This is JB Pritzker’s keynote at the Midwest Entrepreneur’s Summit. (If the video doesn’t display for you, click here).

This is a pretty good talk, but thinking about it a bit, a few things jumped out at me.

First, this is a talk in the finest tradition of “the sun is always shining on Chicago.” I’ve noted many times that under the Daley administration there was in effect a gag rule against saying anything that could be construed as even slightly negative about the city. I’ve noticed a change in that under Emanuel, but there’s one big exception, and that’s the tech sector. In Chicago tech pretty much everybody is pretty much 100% on the rails of the marketing message all of the time.

Listening to this, you’d think Chicago basically is tech nirvana, with the exception of a central gathering place for techies, something that Pritzker conveniently has a plan to create. Strong as Chicago may be, I can’t believe everything could possibly be this rosy. Similar sentiments from various members of the tech community are prominently on display in pretty much every article out there.

There’s nothing wrong with being a champion for your city, but when you become too much the booster club society, it’s not healthy. A little more paranoia and a little less spin would probably do the city good. Chicagoans would clearly recognize the excess earnestness that characterizes such rhetoric if they saw it in another city – I see it all over the place, as all kinds of cities make the case for why they too are one of the next great tech hubs by closing ranks and presenting a unified, totally positive marketing front to the outside world – so I’d suggest they think about how they’d evaluate the statements they make if those same statements were being made by boosters of another place like say Kansas City.

Here’s another example. Announcing some additional protected bike lanes, Rahm Emanuel had this to say:

It’s part of a planned bike lane network that Mayor Rahm Emanuel on Sunday said will help Chicago to attract and keep high tech companies and their workers who favor bicycles.

“By next year I believe the city of Chicago will lead the country in protected bike lanes and dedicated bike lanes, and it will be the bike friendliest city in the country,” Emanuel said Sunday at Malcolm X College.

“It will help us recruit the type of people that have been leaving for the coast. They will now come to the city of Chicago. The type of companies that have been leaving for the coast will stay in the city of Chicago.”

I like protected bike lanes. I applaud Chicago’s protected bike lane program. But this is a bit over the top. I got unsolicited email from as far away as the West Coast mocking this.

I think Emanuel’s media savvy and willingness to sell Chicago is a big plus for the city. But he has had a tendency to sometimes step over the line and make extravagant statements that just don’t pass the sniff test. I think this comes from his days in Washington where that sort of thing is expected, understood, and discounted by everyone. It’s just the way the game is played there. But for mayors there’s a different standard of judgement. Yes, everyone expects you to make the aggressive case for your city. But mayoral statements that seem un-moored from reality – like the various claims that have been made about crime and shootings, for example – end up calling into question the truth of everything else you say. This in my view is a danger for Rahm or anyone else who has been overly steeped in Beltway style communications.

So I would suggest that Chicago continue to be aggressive on marketing, but tone down some of the orgasmic rhetoric and take care that they don’t end up believing too much of their own press. This can be a fine line to walk. I hope that in private at least the city’s tech community has a huge punch list of things that need to be better they are actively working on.

Better Tech Media

Another aspect of Pritzker’s talk that jumped out at me immediately at the time he gave it (I attended the event), was his failure to mention that Chicago already had a very successful version of his own 1871 incubator called Tech Nexus. Tech Nexus is a self-described “clubhouse” for Chicago’s tech community, a co-working space, and an incubator (ranked one of the top ten in the United States by Forbes) that has served over 100 companies. Tech Nexus also hosts tons of meetups and other events, and through the affiliated Illinois Technology Association has been an instrumental booster of the Chicago tech scene the last few years.

Now Pritzker did mention them in passing in a long list of institutions he gave in the talk. But to claim Chicago lacked the central gathering place for tech until he, JB, rode to the rescue with 1871 is a) not true and b) pretty obviously a deliberate snub of Tech Nexus.

I certainly don’t think everybody needs to be on the same page in a city’s tech community. I actually think that would be a weakness. I think it’s healthy to have different groups of people with different visions each pushing them. Building a space like 1871 is a positive. The more the merrier I say. But this type of talk smells to me like pretty much just a political power play in the Chicago tech community.

Speaking of which, Pritzker may be a venture capitalist, but he’s also an heir to the Pritzker family fortune and one of the richest men in America. (Oh, the irony of having as the keynote speaker for your entrepreneurship conference a guy who inherited over a billion dollars – that tells you a lot about how Chicago works). The Pritzkers have long been power players in Chicago and a key part of what I’ve called the Nexus. So being on the executive committee of World Business Chicago is not so far a leap as he may have us believe. (I also wonder if perhaps Pritzker is the guy who convinced Emanuel to make the very risky move of piling all those chips on the tech square, as he’d appear to be one of the few guys with an interest who would have the clout to do it).

My point here isn’t to bash JB Pritzker, but rather to wonder why no one is asking questions or talking about stuff like this in the press. There are lots of very rich guys with no doubt big egos involved Chicago tech. There’s bound to be lots of interesting politics and personality clashes and maneuverings going on behind the scenes. I want to be able to pop some popcorn and follow the drama. But it doesn’t get covered. I think the local media is basically out of their depth when it comes to covering Chicago tech.

My believe is that Chicago needs a new, independent media source covering the local tech market. This would not be part of the marketing machine of Chicago tech, though like TechCrunch would of course be institutionally favorable to the industry, but instead would provide real, credible coverage of the what’s what and who’s who of the community. As Mark Suster said in the post I linked to earlier, “Local press matters.”

In my review of Enrico Moretti’s book, I noted how he took a face value some mainstream media reports on how tech giants like Facebook were acquiring startups just to get their talent while shutting down the actual companies. He apparently didn’t read Gawker, which gave a fuller story. New York tech community also benefits from other sites, such as the irreverent Betabeat from the New York Observer. Suster mentions sites like GeekWire in Seattle and SoCalTech as well but I don’t know them personally so can’t say they’d be the models to replicate.

In any event, I believe Chicago needs a first class tech media site. A site like Technori does a good job, but it strikes me more as a “how to” site than a media property. Chicago needs a someone asking tough questions, and looking at the people and politics around tech, not just the bits and the bytes. Because IMO the traditional Chicago media hasn’t really shown any interest in pursuing this.

Why Digital?

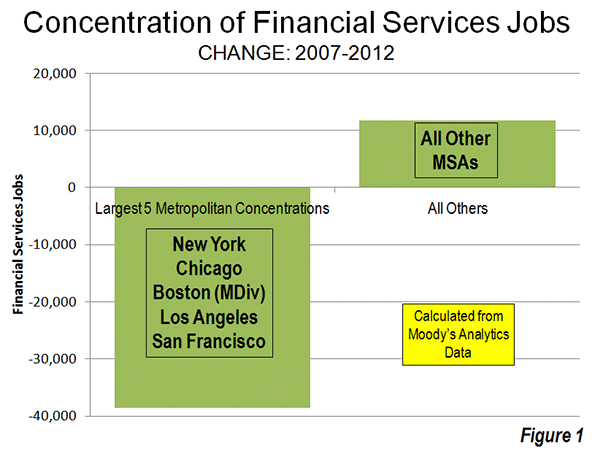

I’m also a bit puzzled as to why Chicago is leading its marketing with the digital/social media/consumer space. Obviously Groupon (which seems to be in the process of getting airbrushed out of the Chicago tech politburo photo) played a role in this. But this seems like a shaky place to stake a claim. I don’t see consumer type brands as Chicago’s strong suit, and the digital market seems weak in any case. Even juggernaut type companies like Facebook and Groupon have struggled financially. There’s a big question mark over the whole space. What’s more, it seems like lots of places, ranging from San Francisco to New York, are rushing to tell basically the same story in digital and are frankly ahead in the space.

By contrast, Chicago has a long and successful history of business to business and information technology. Flip Filipowski’s Platinum Technology was a great example of this. These types of companies might not have the sexiest brands, but they deliver value and make money. What’s more, because of the support demands of corporate clients, these businesses often employ a material amount of highly skill, highly paid people, unlike most digital startups.

Also, Chicago has been a major center of corporate IT for a long time. This is often not valued by the pure tech crowd, but is a huge source of value and good paying jobs. Terry Howerton (who runs TechNexus) said of State Farm:

“State Farm has 12,000 employees in IT in Bloomington,” Howerton said. “I’m sure many of those employees are really smart people, but how innovative can you be with 12,000 IT workers in your bureaucratic corporate environment in an industry as historic as insurance?”

Well, to start with, 12,000 IT employees is likely more than the total local employee count of every digital startup in Chicago combined. And that’s just one company. Howerton is the best advocate out there for a B2B vision for Chicago tech, but I would also add the IT part to the equation as well.

Chicago’s IT shops have a long track record of innovation going back to before a lot today’s digital folks were even born. Walgreen’s Intercom system, for example, linked all their pharmacies nationwide together back in the 1980s so that you could get your prescription refilled anywhere you needed it. And they didn’t have today’s open systems and frameworks to make life easy. They had to use a proprietary satellite system and a specialized high volume, 24×7 uptime mainframe operating system called TPF (originally developed for airline reservations). I’m not sure most of today’s digital coders could figure out how to build and support a TPF application if their lives depended on it.

Given Chicago’s heritage as a center for professional and business services, and corporate headquarters, I believe its natural strengths in technology are in B2B tech companies, technology consulting, and corporate IT. If you can get digital/consumer startups that’s great, but I wouldn’t make that the public face of the city. Instead, take all that corporate services mojo and embed it in tech.

The Big Risk

If you look at what I’ve written about changes so far, most of them are tweaks around the margins. They don’t indicate core weaknesses. Frankly they are sort of nit-picky. That should tell you something. As I said, I think the Chicago market has been doing well – better than I thought it would. I’m not even concerned about the so-called “developer drought” of which I’m extremely skeptical (see more here).

But there’s one thing that is a clear risk to Chicago, one that could undo all its effors – and it’s one that the city can’t do anything about. That’s the risk of another tech crash.

Technology is very cyclical. Every so often, Silicon Valley has had a major crash. I believe it is these crashes that have actually helped to keep the tech industry concentrated in its major hubs. That’s because when crashes come, industries retrench and reconsolidate. For example, Joel Kotkin has said that it was actually the 1980’s energy crash, the one that devastated Houston, that actually helped trigger the industry consolidation there. We’re seeing something similar in media, where financial pressure is consolidating it into NYC and to a somewhat lesser extent DC while secondary markets get wiped out.

So too in tech. Think about the dot com era. Lots of cities had their startup dreams back then too, and it seemed like parts of the country outside the major hubs would be able to get their bite at the apple. Chicago had its “Silicon Prairie” and New York its “Silicon Alley.” All of them got blown up by the dot com crash. But Silicon Valley and Boston survived. Chicago and New York tech eventually came back, but it was on a totally new basis.

There’s a tendency locally in Chicago to now talk about the flaws of the city’s tech ambitions in the Silicon Prairie days in contrast to how it now has its act together. The idea is that Silicon Prairie collapsed because people didn’t get along, or because they chased away their entrepreneurs, etc. But the reality is that it most likely collapsed simply because the market did, not because of flaws or mistakes. I’m not convinced there’s anything the city could have done to survive that shakeout. And if another crash hit, the same thing might easily happen all over again.

We’re seeing the early part of the cycle repeat again today. We’ve had a frothy investment climate with a spread of tech around the country to a whole slew of me-too places. But as I said, the whole digital startup thing has questions marks. It’s not clear that there’s a lot of sustainable, cash generating businesses out there. Many of them (e.g. Groupon) are not even really tech companies. A lot of them are basically media type entities, and like much media in the world have more eyeballs than profits.

Regardless of whether the digital wave crashes soon, another tech crash would appear to be inevitable at some point. If it happens at a time when Chicago hasn’t built some sort of a sustainable franchise, that would be bad. Right now, I don’t believe the Chicago tech scene as currently conceived would survive a major crash. I’m somewhat skeptical New York’s would either. That’s not because the city is doing anything wrong, but because of where it is in the maturity cycle.

That is really the key weakness in the Chicago story. It’s not the fortress hub that Silicon Valley is. I believe it is benefiting from a general decentralization of tech along with a boom cycle investment climate. That can be very good for Chicago, but unless and until it can turn the corner into something that can survive the next big crash, there will continue to be a major question mark over its viability.

This is what I find most interesting about Rahm’s all-in bet on tech. The last go round ended badly. There’s lots of reasons to believe Chicago can be a strong player in the current market, but the city doesn’t have intuitive structural advantages that would make it a slam dunk candidate to become a fortress hub in tech. The digital market is looking somewhat questionable, as the stock charts on Groupon and Facebook show. This was a risky bet. Not to say a bad one, but a risky one. That’s why I think it would be a very intriguing story to find out how it came to be.

In the meantime, while we wait for the judgement of history, Chicago should enjoy where it’s at, build on the present success, and look to shore up those addressable areas of weakness around an excessive booster club mentality, the need for stronger media, and getting away from an overly digital based marketing approach to Chicago tech.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Photo by Doug Siefken