The evolution of cities is a protean process–and never more so than now. With over 50% of people living in metropolitan areas there have never been so many rapidly rising urban areas–or so many declining ones.

Our list of the cities of the future does not focus on established global centers like New York, London, Paris, Hong Kong or Tokyo , which have dominated urban rankings for a generation. We have also passed over cities that have achieved prominence in the past 20 years such as Seoul, Shanghai, Singapore, Beijing, Delhi, Sydney, Toronto, Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth.

Nor does our list include the massive, largely dysfunctional megacities–Mumbai, Mexico City, Dhaka, Bangladesh–that are among planet’s most populous today. Bigger often does not mean better.

Instead, our list focuses on emerging powerhouses like Chongqing, China, (population: 9 million), which Christina Larson in Foreign Policy recently described as “the biggest city you never heard of.”

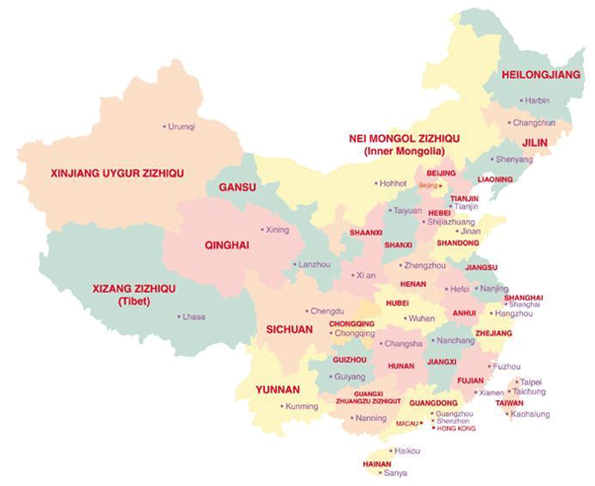

Chongqing sits in the world’s most important new region for important cities: interior China. These interior Chinese cities, notes architect Adam Mayer, offer a healthy alternative to coastal megacities such as Shanghai, Hong Kong, Shenzen and Guangzhou, which suffer from congestion, high prices and increasingly wide class disparities. China’s bold urban diversification strategy hinges both on forging new transportation links and nurturing businesses in these interior cities. For example, in Chengdu, capital of the Sichuan province, new plane, road and rail connections are tying the city to both coastal China and the rest of the world. And the city is abuzz with new construction, including an increasing concentration of high-tech firms such as Dell and Cisco.

India, although not by plan, also is experiencing a boom in once relatively obscure cities. Its rising urban centers include Bangalore (home of Infosys and Wipro), Ahmedabad (whose per-capita incomes are twice that of the rest of India) and Chennai (which has created 100,000 jobs this year). Many of India’s key industries–auto manufacturing, software and entertainment–are establishing themselves in these cities.

The growth of India and China also creates opportunity for other emerging players, particularly in Southeast Asia by creating markets for goods and services as well as investment capital. Potential hot spots include places like Hanoi, Vietnam, which is attracting greater interest from Japanese, American and European multi-national firms upset with China’s often bullying trade practices and rising costs. Malaysia’s capital Kuala Lumpur–with its rising financial sector–also displays considerable promise.

Africa also boasts many huge, rapidly growing cities, but it’s hard to identify many of these places–like Lagos, Nigeria, Luanda, Angola or Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo–as bright prospects. One exception may well be Cape Town, the beautiful South African coastal city that shone so well during the recent World Cup.

Latin America, too, has a plethora of huge and growing cities, but it’s hard to nominate the likes of Mexico City or Sao Paulo as likely hot spots for future sustainable growth.

The best economic prospects in this region lie in more modestly sized cities like Santiago, the capital of resource-rich Chile, and even Campinas, Brazil, a growing smaller city–with 3 million residents–that lies outside the congested Sao Paolo region. This shift to smaller-scaled cities, as Michigan State’s Zachary Neal points out, has been conditioned by massive improvements in telecommunications and transportation infrastructure throughout the urban world. Today, he asserts, it is the ability to network long-distance–not girth–that makes the critical difference.

This is clear in the Middle East, where the emerging stars tend to be smaller cities. Tel Aviv, whose total metropolitan area is no larger than 3 million, has emerged as a major center for technology as well as one of the world’s premier diamond centers. The other leading candidates in the region hail from the United Arab Emirates, notably oil-rich Abu Dhabi and perhaps its now weakened neighbor, Dubai.

In North America the best urban prospects–Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; Austin, Texas; Salt Lake City; and Calgary, Canada–are far smaller than homegrown giants New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. Generally business-friendly and relatively affordable, these cities will attract many talented millennials as they start forming families in large numbers later in this decade.

Europe’s urban problem lies with stagnant or slow-growing population levels, and in the south at least, very weak economies. The only rapidly growing big city lies on the region’s periphery: Istanbul, which straddles the border between Europe and Asia and faces many of the problems common to developing-country mega-cities.

Overall, the populations of Europe’s cities are growing at barely 1%, the lowest rate of any continent. With low birthrates and growing opposition to immigration, it seems unlikely that any European city will emerge as a bigger global player in 20 years than today.

Other leading cities all over the world may also be in the early stages of fading from predominance. In the United States, according to analysis by the California Lutheran University forecast, Los Angeles and Chicago, America’s second and third cities, respectively, have fallen behind not only fast-comers like Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth, but even historically dominant New York in such key indicators as job generation and population growth.

Similarly Berlin, once seemingly poised to thrive in the post-Cold War future, has chronic high unemployment and a weak private sector, compared with Germany’s generally smaller, less unruly successful cities. The Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto area in Japan may also be set to fade a bit, due largely to the overwhelming predominance of Tokyo and the general demographic and economic decline of Dai Nippon.

Of course, none of this is set in stone. But this list provides an educated peek into which cities are best positioned to prosper and grow in our emerging era of cities.

Chengdu, China

The development of interior China, long on the back burner of national priorities, has reached the country’s western-most large city. Chengdu is abuzz with new construction, including an increasing concentration of high-tech companies, including Dell and Cisco. New plane, road and rail connections are tying the city to both coastal China and the rest of the world. With a metropolitan population of 6 million, economic factors–including lower costs–may prove critical to the capital of the Sichuan province. The business-friendly city still has a way to grow to catch up to the GDP per capita of Shanghai.

Chongqing, China

Chongqing enjoys rapidly improving transportation links with its neighbors to the west and the coastal megacities. Foreign companies like Ford, Microsoft, Hewlett Packard and Singapore-based Neptune Orient Lines are flocking to the city. The Business Times of Singapore reports that since 1998, Chongqing’s GDP has quadrupled from $21 billion to $86 billion. Last year alone, Chongqing’s GDP expanded at almost twice the rate of China as a whole. The population, according to United Nations projections, should grow from 9 million to 11 million by 2025.

Chongqing, China

Chongqing enjoys rapidly improving transportation links with its neighbors to the west and the coastal megacities. Foreign companies like Ford, Microsoft, Hewlett Packard and Singapore-based Neptune Orient Lines are flocking to the city. The Business Times of Singapore reports that since 1998, Chongqing’s GDP has quadrupled from $21 billion to $86 billion. Last year alone, Chongqing’s GDP expanded at almost twice the rate of China as a whole. The population, according to United Nations projections, should grow from 9 million to 11 million by 2025.

Ahmedabad, India

This is the largest metropolitan region in Gujarat, perhaps the most market-oriented and business-friendly of Indian states. Gujarat’s policies helped lure away the new Tata Nano plant from West Bengal (Kolkata) to Sanand, one of Gurajat’s exurbs. One Indian academic, Sedha Menon, compares the state–which has developed infrastructure more quickly than its domestic rivals–with Singapore and parts of Malaysia. Per-capita incomes in Gujarat are more than twice the national average. India’s seventh-largest city has a population of roughly 5.7 million and is expected, according to the U.N., to grow to over 7.6 million by 2025.

Santiago, Chile

Santiago boasts a diversified economic base: mining, textile production, leather technologies and food processing. Its favorable investment climate has enticed many multinational companies; there are few restrictions on foreign investment, and transparency is extensive. Recent surveys have ranked Chile and Santiago as leading locations in Latin America in terms of competitiveness. The 2010-2011 Global Competitiveness Report ranked Chile the highest in terms of competitiveness (based on institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, education, market efficiency, financial market development, et. al).

Raleigh Durham, North Carolina

Even in hard times this low-density, wide-ranging urban area has repeatedly performed well on Forbes’ list of the best cities for jobs. The area is a magnet for technology firms fleeing the more expensive, congested and highly regulated northeast corridor. One big problem obstructing the region’s ascendancy has been air connections. But Delta recently announced a large-scale expansion of flights there from around the country. Population growth will likely be lead by educated millennials seeking affordable housing and employment opportunities. Today the region has 1.7 million residents; the State of North Carolina projects it will grow to 2.4 million by 2025.

Tel Aviv, Israel

This urban region of roughly 3 million may boast the most vibrant economy of any along the Mediterranean. Tel Aviv and its surrounding environs control the vast majority of Israel’s high-tech exports, making it what may well be the closest thing to a Silicon Valley outside East Asia or California. It also boasts a household income that is nearly 50% above the national average for Israel. But perhaps its greatest asset is its free-wheeling lifestyle: Tel Aviv combines an Israeli entrepreneurial culture with the attributes of a thriving seacoast town.

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Kuala Lumpur’s prospects lie in a development strategy focused on improving its air service, road and trade infrastructure, much as occurred in previous decades in Singapore. The urban area’s population has grown to over 5.8 million, and demographer Wendell Cox projects a population of roughly 8.2 million by 2025. KL has emerged as a global Islamic financing hub and maintains close ties with the Arabian Gulf’s finance sector. Educational and health care institutions also bolster the city’s growth. Forbes lists Kuala Lumpur as one of Asia’s future financial centers.

Suzhou, China

As in the U.S., some of the fastest-growing cities in China are located close to the bigger cities. Suzhou, only 75 miles from Shanghai, seems well positioned to benefit from spillover growth from the megacity. Known as the Venice of China, with many attractive canals and vast international tourism potential, its beauty and history could help secure its aspiration to become “the world’s office.” Some reports suggests Suzhou may already be the most affluent city in China; demographer Wendell Cox estimates that per-capita income is more than three times that of interior cities like Chengdu.

Hanoi, Vietnam

Chinese, Japanese, American, Singaporean, European and Indian companies identify this fast-growing city as ripe for industrial and infrastructure growth. The population of the region has doubled since the end of the Vietnam War to almost 3 million, and the U.N. projects a population of 4.5 million by 2025. Along with Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), Hanoi is expected be one of the fastest-growing GDPs in the world. Hanoi’s GDP growth rate for the first nine months of 2010 was estimated at 10.6%, almost twice that for the same period of last year.

Chennai, India

Formerly known as Madras, this metropolitan area of 7.5 million, up from 4.7 million 20 years ago, is projected by the U.N. to approach 10 million by 2025. Located on India’s east Asian coast, the city has so far this year created over 100,000 jobs–more than any other Indian city outside of the much larger Delhi and Mumbai. Chennai’s metropolitan area is taking full advantage of India’s soaring industrial sector, particularly the booming automobile sector. Electronics, led by Dell, Nokia, Motorola, Samsung, Siemens, Sony and Foxconn, are also booming. Chennai is home to India’s second-largest entertainment industry, behind Mumbai.

Austin, Texas

Austonites tend to be smug–but they have good reason. The central Texas city ranked as the No. 1 large urban area for jobs in our last Forbes survey. Along with Raleigh-Durham, Austin is an emerging challenger for high-tech supremacy with Silicon Valley. The current area’s population is 1.7 million and is expected to grow rapidly in the coming decades. Austin owes much both to its public sector institutions (the state government and the main Campus of the University of Texas) and its expanding ranks of private companies–including foreign ones–swarming into the city’s surrounding suburban belt.

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Oil rich Abu Dhabi is among the world’s wealthiest countries in terms of per-capita GDP, which exceeds $68,000. However, the non-oil sector is likely to grow to about 45% of the GDP in coming years. To do so, the government has started to invest its oil revenues in construction, tourism and the electricity and water industry. Abu Dhabi is also helping to keep its neighbor Dubai afloat. If Dubai, with its world class infrastructure, can make a comeback, a global city separated by 80 miles of desert Arabian Gulf coastline could arise.

Campinas, Brazil

Campinas, located around 50 miles north of São Paulo, the country’s dominant industrial center, has attracted many technology companies, including IBM, Dell, Compaq, Samsung and Texas. The city also boasts a major research and university center. Firms engaged in high-tech activities–following a global pattern–tend to cluster in relatively pleasant, affordable and efficient places. Campinas could prove a big Brazilian beneficiary of this trend.

Melbourne, Australia

Australia has resources galore and relatively few people. But which of its cities is poised to benefit most from the nation’s expanding trade with China and India? Sydney’s costs have been shooting up–particularly for housing, but Melbourne’s political class seems about to open up new land for suburban development to restore some of the area’s affordability for younger Australians. Demographer Bernard Salt has predicted that Melbourne’s population will exceed Sydney‘s in less than 20 years. Melbourne also boasts Australia’s most walkable and pleasant urban cores , a pleasant San Francisco-like climate and a European ambiance.

Bangalore, India

Many big players in tech and services–Goldman Sachs, Cisco, HP as well as India-based giants like Tata–have located operations in Bangalore. But the city also boasts home-grown tech giants Infosys and Wipro, which each have over 60,000 employees worldwide. Since 1985 Bangalore’s population has more than doubled to over 7 million and is projected by the U.N. to reach 9.5 million by 2025. In the future, maintaining Bangalore’s advantage over smaller, less congested cities could prove a challenge.

Salt Lake City, Utah

Once seen as a Mormon enclave, the greater Salt Lake urban area–with roughly 1 million people –has every sign of emerging as a major world player with a wider appeal. The church still plays a critical role, in part by financing a massive redevelopment of the city’s now rather dowdy city core. The area’s population has doubled since the early 1970s and will grow another 100,000 by 2025 to well over 1.1 million. New companies are flocking to this business-friendly region, particularly from self-imploding California. Increasing national and global connections through Delta’s hub will tie this once isolated city closer with the wider world economy.

Nanjing, China

The one-time Imperial and Republican (Nationalist) capital sits only 150 miles from Shanghai. The relative affordability of Nanjing has drawn huge construction projects to the city, which is also the capital of Jiangsi Province. The city is developing a transport hub, and huge commercial construction projects abound in the downtown area. A majority of employment is in the fast-growing service sector. The metropolitan economy grew 50% just between 2006 and 2008, and future rapid growth is likely.

Cape Town, South Africa

The second-largest city in South Africa behind Johannesburg, Cape Town made the most of the recent World Cup. The region of some 3 million boasts fast-growing communications, finance and insurance sectors. Cape Town is looking to intellectual capital, transportation assets, business costs, technology, innovation and ease of doing business as its primary assets. In 2009 Empowerdex rated Cape Town as the top-performing municipality in South Africa for service delivery. About 97% of the operational budget went to infrastructure development, ensuring that households can enjoy adequate sanitation and water access.

Calgary, Canada

You don’t have to buy the notion of a climate-change-driven northern ascendancy to see a bright future for Alberta’s premier city. Calgary is positioned well on the fringe of Canada’s largest energy belt and enjoys lower taxes and less stringent regulations than its Canadian rivals. Calgary has been hit by a slowdown in energy business, but over time demand from China, India and a slowly recovering world economy should boost this critical sector. The region is expected to be back to its familiar place on top among Canadian urban economies by next year.

The World’s Diminishing Cities: Chicago, Ill.

Great cities don’t only rise, some decline. Even with Barack Obama in the White House, Chicago is struggling with persistent job losses that, since 2000, are exceeded only by Detroit among the nation’s top 10 largest U.S. regions. The Windy City’s deficit as a percentage of spending–a remarkable 16.3 %–is now higher than Los Angeles and twice that of New York. Moreover, crime remains stubbornly high, and the widely hyped condo boom has left a legacy of uncompleted buildings, foreclosures and vacancies.

The World’s Diminishing Cities: Berlin, Germany

By all rights, Berlin should be a European boomtown: The capital of united Germany, a natural crossroads to the east and Europe’s bohemian hot spot. But it remains, as its mayor, Klaus Wowereit, famously remarked, “poor but sexy.” Berlin suffers unemployment far higher than the national average, and its gross added-value per inhabitant amounted to just over half that created by residents in the northern city of Hamburg, which has about half as many people. One-quarter of the workforce earns less than 900 euros a month, and one out of every three children lives in poverty.

The World’s Diminishing Cities: Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, Japan

Few places possess a more glorious urban pedigree than Japan’s Kansai region. But the shift of manufacturing to China and other countries has undermined the economy of Osaka, traditionally the industrial heart of Japan. As Japan shrinks both economically and demographically, Tokyo, the world’s largest city, looms ever larger while Osaka’s role is, as one demographer put it, “fading away.” Tokyo’s population, now over 30 million, has grown to be double that of the Osaka region, and continues to outpace it. Most critical: It is to Tokyo, not Osaka, that Japan’s diminishing reserves of educated young people–and industries dependent on their talent–are headed.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History . His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050 , released in February, 2010.

, released in February, 2010.

Photo by Sarmu

Tribal ties—race, ethnicity, and religion—are becoming more important than borders.

For centuries we have used maps to delineate borders that have been defined by politics. But it may be time to chuck many of our notions about how humanity organizes itself. Across the world a resurgence of tribal ties is creating more complex global alliances. Where once diplomacy defined borders, now history, race, ethnicity, religion, and culture are dividing humanity into dynamic new groupings.

Broad concepts—green, socialist, or market-capitalist ideology—may animate cosmopolitan elites, but they generally do not motivate most people. Instead, the “tribe” is valued far more than any universal ideology. As the great Arab historian Ibn Khaldun observed: “Only Tribes held together by a group feeling can survive in a desert.”

Although tribal connections are as old as history, political upheaval and globalization are magnifying their impact. The world’s new contours began to emerge with the end of the Cold War. Maps designating separate blocs aligned to the United States or the Soviet Union were suddenly irrelevant. More recently, the notion of a united Third World has been supplanted by the rise of China and India. And newer concepts like the BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) are undermined by the fact that these countries have vastly different histories and cultures.

The borders of this new world will remain protean, subject to change over time. Some places do not fit easily into wide categories—take that peculiar place called France—so we’ve defined them as Stand-Alones. And there are the successors to the great city-states of the Renaissance—places like London and Singapore. What unites them all are ties defined by affinity, not geography.

Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden

In the 13th century, an alliance of Northern European towns called the Hanseatic League created what historian Fernand Braudel called a “common civilization created by trading.” Today’s expanded list of Hansa states share Germanic cultural roots, and they have found their niche by selling high-value goods to developed nations, as well as to burgeoning markets in Russia, China, and India. Widely admired for their generous welfare systems, most of these countries have liberalized their economies in recent years. They account for six of the top eight countries on the Legatum Prosperity Index and boast some of the world’s highest savings rates (25 percent or more), as well as impressive levels of employment, education, and technological innovation.

Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, U.K.

These countries are seeking to find their place in the new tribal world. Many of them, including Romania and Belgium, are a cultural mishmash. They can be volatile; Ireland has gone from being a “Celtic tiger” to a financial basket case. In the past, these states were often overrun by the armies of powerful neighbors; in the future, they may be fighting for their autonomy against competing zones of influence.

Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Italy, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain

With roots in Greek and Roman antiquity, these lands of olives and wine lag behind their Nordic counterparts in virtually every category: poverty rates are almost twice as high, labor participation is 10 to 20 percent lower. Almost all the Olive Republics—led by Greece, Spain, and Portugal—have huge government debt compared with most Hansa countries. They also have among the lowest birthrates: Italy is vying with Japan to be the country with the world’s oldest population.

It’s a center for finance and media, but London may be best understood as a world-class city in a second-rate country.

Paris

Accounts for nearly 25 percent of France’s GDP and is home to many of its global companies. It’s not as important as London, but there will always be a market for this most beautiful of cities.

Singapore

In a world increasingly shaped by Asia, its location between the Pacific and Indian oceans may be the best on the planet. With one of the world’s great ports, and high levels of income and education, it is a great urban success story.

While much of nationalist-religious Israel is a heavily guarded borderland, Tel Aviv is a secular city with a burgeoning economy. It accounts for the majority of Israel’s high-tech exports; its per capita income is estimated to be 50 percent above the national average, and four of Israel’s nine billionaires live in the city or its suburbs.

5. North American Alliance

These two countries are joined at the hip in terms of their economies, demographics, and culture, with each easily being the other’s largest trade partner. Many pundits see this vast region in the grip of inexorable decline. They’re wrong, at least for now. North America boasts many world-class cities, led by New York; the world’s largest high-tech economy; the most agricultural production; and four times as much fresh water per capita as either Europe or Asia.

Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru

These countries are the standard–bearers of democracy and capitalism in Latin America. Still suffering low household income and high poverty rates, they are trying to join the ranks of the fast-growing economies, such as China’s. But the notion of breaking with the U.S.—the traditionally dominant economic force in the region—would seem improbable for some of them, notably Mexico, with its close geographic and ethnic ties. Yet the future of these economies is uncertain; will they become more state–oriented or pursue economic liberalism?

Argentina, Bolivia, Cuba, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Venezuela

Led by Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, large parts of Latin America are swinging back toward dictatorship and following the pattern of Peronism, with its historical antipathy toward America and capitalism. The Chávez-influenced states are largely poor; the percentage of people living in poverty is more than 60 percent in Bolivia. With their anti-gringo mindset, mineral wealth, and energy reserves, they are tempting targets for rising powers like China and Russia.

South America’s largest economy, Brazil straddles the ground between the Bolivarians and the liberal republics of the region. Its resources, including offshore oil, and industrial prowess make it a second-tier superpower (after North America, Greater India, and the Middle Kingdom). But huge social problems, notably crime and poverty, fester. Brazil recently has edged away from its embrace of North America and sought out new allies, notably China and Iran.

France remains an advanced, cultured place that tries to resist Anglo-American culture and the shrinking relevance of the EU. No longer a great power, it is more consequential than an Olive Republic but not as strong as the Hansa.

India has one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, but its household income remains roughly a third less than that of China. At least a quarter of its 1.3 billion people live in poverty, and its growing megacities, notably Mumbai and Kolkata, are home to some of the world’s largest slums. But it’s also forging ahead in everything from auto manufacturing to software production.

With its financial resources and engineering savvy, Japan remains a world power. But it has been replaced by China as the world’s No. 2 economy. In part because of its resistance to immigration, by 2050 upwards of 35 percent of the population could be over 60. At the same time, its technological edge is being eroded by South Korea, China, India, and the U.S.

South Korea has become a true technological power. Forty years ago its per capita income was roughly comparable to that of Ghana; today it is 15 times larger, and Korean median household income is roughly the same as Japan’s. It has bounced back brilliantly from the global recession but must be careful to avoid being sucked into the engines of an expanding China.

It’s essentially a city-state connected to the world not by sea lanes but by wire transfers and airplanes. It enjoys prosperity, ample water supplies, and an excellent business climate.

Armenia, Belarus, Moldova, Russian Federation, Ukraine

Russia has enormous natural resources, considerable scientific-technological capacity, and a powerful military. As China waxes, Russia is trying to assert itself in Ukraine, Georgia, and Central Asia. Like the old tsarist version, the new Russian empire relies on the strong ties of the Russian Slavic identity, an ethnic group that accounts for roughly four fifths of its 140 million people. It is a middling country in terms of household income—roughly half of Italy’s—and also faces a rapidly aging population.

Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan

This part of the world will remain a center of contention between competing regions, including China, India, Turkey, Russia, and North America.

Bahrain, Gaza Strip, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria

With oil reserves, relatively high levels of education, and an economy roughly the size of Turkey’s, Iran should be a rising superpower. But its full influence has been curbed by its extremist ideology, which conflicts not only with Western countries but also with Greater Arabia. A poorly managed economy has turned the region into a net importer of consumer goods, high-tech equipment, food, and even refined petroleum.

Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Palestinian Territories, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen

This region’s oil resources make it a key political and financial player. But there’s a huge gap between the Persian Gulf states like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates and the more impoverished states. Abu Dhabi has a per capita income of roughly $40,000, while Yemen suffers along with as little as 5 percent of that number. A powerful cultural bond—religion and race—ties this area together but makes relations with the rest of the world problematic.

Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

Turkey epitomizes the current reversion to tribe, focusing less on Europe than on its eastern front. Although ties to the EU remain its economic linchpin, the country has shifted economic and foreign policy toward its old Ottoman holdings in the Mideast and ethnic brethren in Central Asia. Trade with both Russia and China is also on the rise.

Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zimbabwe

South Africa’s economy is by far the largest and most diversified in Africa. It has good infrastructure, mineral resources, fertile land, and a strong industrial base. Per capita income of $10,000 makes it relatively wealthy by African standards. It has strong cultural ties with its neighbors, Lesotho, Botswana, and Namibia, which are also primarily Christian.

Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo-Kinshasa, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia

Mostly former British or French colonies, these countries are divided between Muslim and Christian, French and English speakers, and lack cultural cohesion. A combination of natural resources and poverty rates of 70 or 80 percent all but assure that cash-rich players like China, India, and North America will seek to exploit the region.

Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia

In this region, spanning the African coast of the Mediterranean, there are glimmers of progress in relatively affluent countries like Libya and Tunisia. But they sit amid great concentrations of poverty.

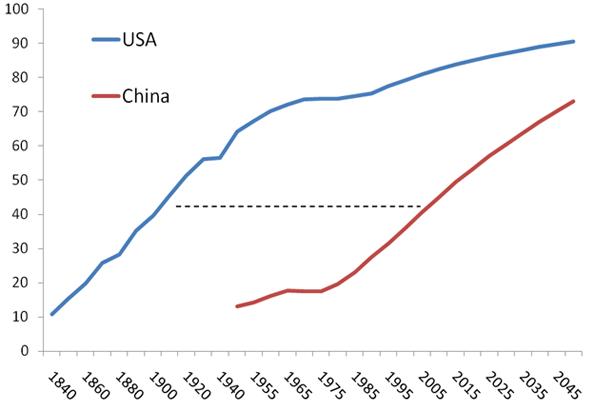

China may not, as the IMF recently predicted, pass the U.S. in GDP within a decade or so, but it’s undoubtedly the world’s emerging superpower. Its ethnic solidarity and sense of historical superiority remain remarkable. Han Chinese account for more than 90 percent of the population and constitute the world’s single largest racial-cultural group. This national cultural cohesion, many foreign companies are learning, makes penetrating this huge market even more difficult. China’s growing need for resources can be seen in its economic expansion in Africa, the Bolivarian Republics, and the Wild East. Its problems, however, are legion: a deeply authoritarian regime, a growing gulf between rich and poor, and environmental degradation. Its population is rapidly aging, which looms as a major problem over the next 30 years.

Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam

These countries are rich in minerals, fresh water, rubber, and a variety of foodstuffs but suffer varying degrees of political instability. All are trying to industrialize and diversify their economies. Apart from Malaysia, household incomes remain relatively low, but these states could emerge as the next high-growth region.

Household incomes are similar to those in North America, although these economies are far less diversified. Immigration and a common Anglo-Saxon heritage tie them culturally to North America and the United Kingdom. But location and commodity-based economies mean China and perhaps India are likely to be dominant trading partners in the future.

This article originally appeared in Newsweek.

Legatum Institute provided research for this article.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University and an adjunct fellow with the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History . His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050 , released in February, 2010.

, released in February, 2010.

Illustration by Bryan Christie, Newsweek

Deng Xiaoping, the pragmatic leader who orchestrated China’s ‘reform and opening-up’ 30 years ago, once said that “some areas must get rich before others.” Deng was alluding to his notion that, due to the country’s massive scale, economic development could not happen all at once across China. Planning and implementation of such an economy would take years, even decades, and some areas would inevitably be developed before others.

The logical place to start was the coastal regions of China, with the natural advantage of access to Asian and overseas markets via the South China Sea and Pacific Ocean. Not surprising then that the two areas that benefited most after initial economic reforms were the Yangtze River Delta region in the east and Pearl River Delta region in the south. Both places became international manufacturing centers with numerous factories and busy seaports.

Today, the prosperity of the Yangtze River Delta can be experienced in Shanghai, ‘the Pearl of the Orient’- undoubtedly China’s most modern and cosmopolitan city. Down south in the Pearl River Delta, the city of Shenzhen, chosen by the Central Government as a ‘Special Economic Zone’ in 1980, transformed from a small fishing village to a bustling metropolis of nearly 10 million people in a mere 30 years. Both places best represent China’s economic achievements of the recent past.

Although China’s coastal regions continue to develop, the initial boom has already slowed. Furthermore, foreign investors are beginning to grow weary by the increasing costs of doing business in cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen. Now both international and domestic businesses have their eyes looking towards the interior of the country, where overhead costs are lower and the cities are building the necessary infrastructure to support growth.

China’s vast western region will be perhaps the most exciting economic development story of the next decade. The country’s west includes 6 provinces, 5 autonomous regions and 1 municipality. Overall the entire region comprises a whopping 70% of China’s landmass and 28% of its population. It also currently accounts for 17% of the country’s GDP, but that is set to change for the better.

In 2001, the Chinese government implemented its Western Development Strategy also known as the ‘Go West’ campaign. The lagging economic progress of the region prompted the Central Government to offer incentives for business development, including a 10% corporate income tax reduction. The plan also calls for massive infrastructure development both in urban and rural areas.

Nearly 10 years after the beginning Western Development Strategy, the positive effects are evident in the region’s largest cities. The key cities that have benefitted most so far are Xi’an (capital of Shaanxi Province), Chengdu (capital of Sichuan Province), Kunming (capital of Yunnan Province) and Chongqing (a direct-controlled municipality). These cities form a tight bond, and despite each being within a less than 2 hour flight from one another, each is unique in character and culture.

At the center of this prosperity is the Chengdu-Chongqing Megaregion. About 200 miles apart from each other, the two cities form a combined urban population of about 10 million people. Chengdu and Chongqing are the principal economic, government, and cultural centers that serve a regional population of nearly 110 million (the combined population of Sichuan Province and Chongqing Municipality). Given these demographics, the potential for growth in these two cities is enormous.

In the past, like the ambitious living in our own heartland, those from China’s interior were forced to leave home for the far-off coastal regions to benefit from the country’s economic growth. Migrant workers from Sichuan had it especially difficult, facing employment discrimination due to their strong local accent (seen as low-class by the eastern cosmopolitans) and the misperception that they are lazy workers. Today, the rise of Chengdu-Chongqing Megaregion means that workers from Sichuan need not go far from home in order to find opportunity. This is a considerable departure from China’s migrant worker narrative of the past 30 years.

Increasingly what you see today is a reversal of past emigration trends, as not only young people from the Chengdu-Chongqing Megaregion opt to stay close to home but people from other regions relocate to the interior to take advantage of the growth.

There is a bit of a rivalry between the cities of Chengdu and Chongqing, with much talk about which of the two will become western China’s most important city. In reality they are more like ‘sisters’ as both cities stand to benefit. As my American friend who lived in the area for over 10 years described the relationship, “Chengdu is the fat provincial nobleman to Chongqing’s beer and hot pot steel worker.”

In the case of Chongqing, he is referring to the importance of the city as an industrial center, both in metal manufacturing and natural resource mining (the surrounding area is rich in coal and natural gas). In contrast, Chengdu is quickly becoming a major player in China’s information technology sector.

Much of this has to do with Chengdu’s advantageous geography. Whereas the surrounding terrain in Sichuan and Chongqing is mountainous and hilly, Chengdu lies in a flat, fertile basin, allowing the city to sprawl out. Dubbed the ‘Land of Abundance’ for its long history of agricultural prosperity, Chengdu is today abounding in domestic and foreign investment in high-tech.

The local government has set up the ‘Chengdu Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone (CDHT)’ with 2 locations: the South Park and the West Park. Both areas lie outside the historical city center and are being built on previously undeveloped land. The character of the CDHT is not the dense urban forest of supertall skyscrapers that characterizes other Chinese cities. Rather, a series of modern low-rise office parks can be seen popping up in the CDHT, not dissimilar from what can be found close to where I grew up in Silicon Valley.

Already, international IT behemoths like Intel have established operations in the CDHT, having opened semiconductor assembly and testing facilities. Other American companies look to expand in the CDHT. Just a few days ago Dell Computer announced it would open an operations center in Chengdu, creating 3,000 new jobs. Cisco Systems has also been involved in Chengdu, collaborating with local institutions like the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China in research and development.

Chengdu attracts foreign investment not only because of its lower cost-value compared to other cities in China but because of its efficient infrastructure and logistics. Chengdu’s Shuangliu Airport is national airline Air China’s third major traffic hub after Beijing and Shanghai. The city is also undergoing the construction of a comprehensive subway system with the first line scheduled to open in on October 1st. This line, Line 1, will connect the historic center of the city with the South Park area of the CDHT- making commuting for IT workers who live in the city more reasonable.

Most interestingly, Chengdu is also promoting quality of life when courting business investment. The local government has established what is called a ‘Modern Garden City’ to keep in line with the city’s history as an agricultural base. The sense of the past is strong with locals, and Chengdu is doing everything to preserve this despite the development.

If Deng Xiaoping were still alive today, he would probably be proud to see Sichuan flourishing- after all it is the patient pragmatist’s native region.

Adam Nathaniel Mayer is an American architectural design professional currently living in China. In addition to his job designing buildings he writes the China Urban Development Blog.

Photo by Toby Simkin

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.

A survey of 120,000 temporary migrant workers in urban areas working by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences research center found that only 25 percent would be interested in trading their rural residency permits for urban residency permits. The survey covered working age adults in 106 prefectures with large urban areas.

A survey of 120,000 temporary migrant workers in urban areas working by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences research center found that only 25 percent would be interested in trading their rural residency permits for urban residency permits. The survey covered working age adults in 106 prefectures with large urban areas.

Locating new satellite towns far enough to make commuting infeasible will be a real problem for Beijing. There just is not enough territory in the provincial level municipality. That means the new towns would have to be in the province Hebei, which along with the province level municipality of Tianjin surrounds Beijing.

Locating new satellite towns far enough to make commuting infeasible will be a real problem for Beijing. There just is not enough territory in the provincial level municipality. That means the new towns would have to be in the province Hebei, which along with the province level municipality of Tianjin surrounds Beijing.