China’s cities continue to add population at a rapid rate, despite a significant slowdown in population growth. Although overall population is expected to peak around 2030, the urban population will continue growing until after 2050. China’s cities will be adding more than 250 million new residents in the next quarter century, according to United Nations projections. China’s cities will add nearly as many people as live in Indonesia, the world’s fourth largest country, more than live in Brazil and 10 times as many as live in Australia.

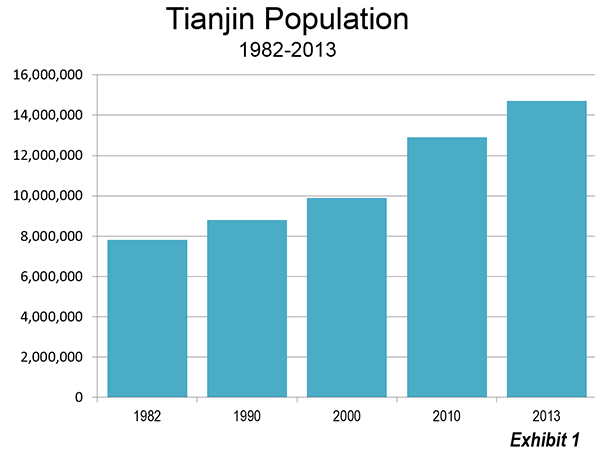

Two of China’s six megacities (urban areas with more than 10 million population) are nearly adjacent, within 90 miles (150 kilometers) of one another. The urban areas of Beijing and Tianjin have a combined population of 35 million and are among the fastest growing in the world. This is an increase of nearly 60% from the 2000 population of 21 million.

The Jing-Jin-Ji Megalopolis

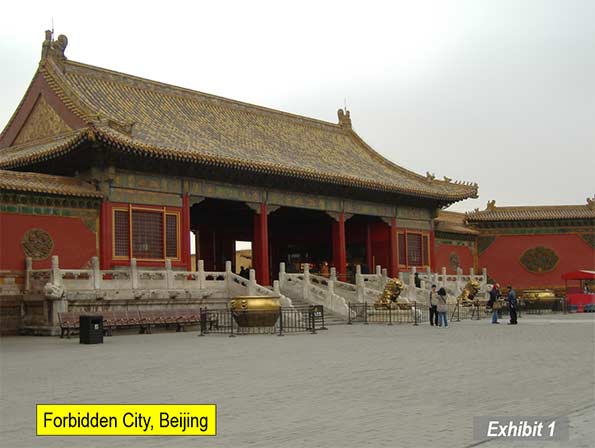

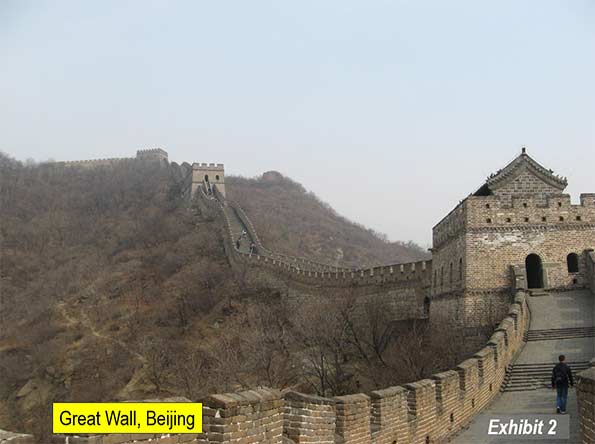

The faster growing of the two, Beijing, is the national capital. Beijing is encircled by five freeway standard ring roads or beltways. These are numbered 2 through 6, with the first ring road being surrounding the Forbidden City. Its population is served by a number of additional expressways and the world’s longest subway. For some time there has been discussion of integrating the metropolitan areas of a much larger region. A principal purpose is dispersion — to redistribute activities, such as government administration and manufacturing away from Beijing’s congested core to peripheral locations.

Over the past year, there have been various announcements describing the process. The megalopolis would be called Jing-Jin-Ji, and would be composed of Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei province. An alternative name would be the "Capital Economic Circle." The name, Jing-Jin-Ji is constructed of the last syllables of "Beijing" and "Tianjin," along with "ji," which is the pronunciation of the one character Mandarin abbreviation for Hebei.

The Need for Dispersal

Beijing has just become too dense and too crowded. Traffic congestion already is among the worst in the world. According to The Sydney Morning Herald, the situation has become so bad that officials intended to limit the population of the Beijing municipality (province) to 23 million, only slightly above the population that is nearing 22 million. They also intend to reduce the population of central districts by 15%.

Important steps are already being taken. Construction has begun on a new facility to house Beijing municipality functions in the suburban district ("qu") of Tongzhou. This subsidiary center is a 40 minute drive from the city center. Tongzhou borders the municipality of Tianjin and, according to the Beijing Municipality government is itself growing about one-quarter faster than the Beijing municipality itself.

There are also plans to move many of the manufacturing facilities that have located in Beijing to the other jurisdictions. The extent of the manufacturing dominance of Beijing is illustrated by the much larger "floating population," of Beijing, which consists of migrants from other parts of the country who lack local residence permission (hukou). According to data in the China Yearbook 2014, Beijing has more than double the ratio to its population of migrant workers as Tianjin and nearly 10 times the ratio of Hebei, which has more than two-thirds of the megalopolis population.

One large automobile manufacturer has already completed moving out of Beijing to Huanghua, a county level city in the Hebei municipality of Cangzhou, which borders Tianjin to the south.

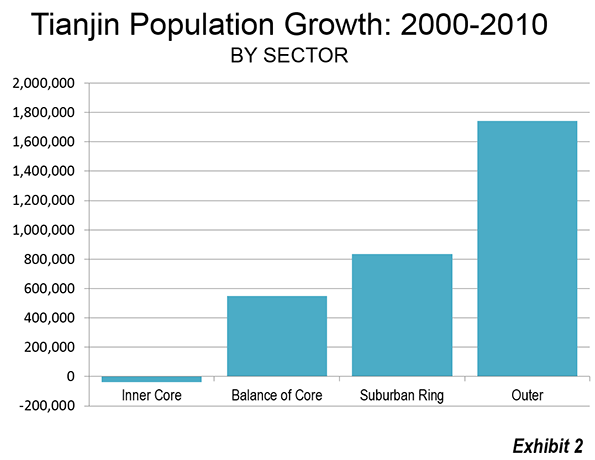

Geography of Jing-Jin-Ji

The jurisdictions comprising Jing-Jin-Ji have approximately 110 million residents. The gross land area is approximately 216,000 square kilometers (83,000 square miles), approximately the land area of Romania or the US state of Idaho. No one, however, should imagine a Phoenix or Portland type sprawl of such a magnitude. As is indicated the Table, the overall population density of Jing-Jin-Ji is only 500 residents per square kilometer (1,300 per square mile). The largest urban areas comprise only 3.5% of the land area, yet contain approximately 40% of the population. Despite the massive urbanization of Beijing and Tianjin, and the other large urban areas, Jing-Jin-Ji has a population that is 40% rural.

| Components of Jing-Jin-Ji | ||||

| Jurisdiction | Total Population (2013) | Density (per KM2) | Principal Urban Area Population (2015) | Urban Density (per KM2) |

| Beijing | 21.2 | 1,300 | 20.2 | 5,100 |

| Tianjin | 14.7 | 1,200 | 10.9 | 5,400 |

| Jing-Jin-Ji Core | 35.9 | 1,300 | 31.1 | 5,200 |

| Baoding | 10.2 | 500 | 1.3 | 5,900 |

| Langfang | 4.4 | 700 | 0.5 | 3,800 |

| Canzhou | 7.2 | 500 | 0.5 | 3,800 |

| Tangshan | 7.5 | 600 | 2.4 | 8,700 |

| Zhangzhiakow | 4.6 | 100 | 1.2 | 9,200 |

| Qinhuangdao | 2.9 | 400 | 1.0 | 6,500 |

| Chengde | 3.7 | 100 | 0.1 | 4,300 |

| Inner Jing-Jin-Ji | 40.5 | 300 | 7.0 | 6,600 |

| Shijiazhuang | 10.4 | 700 | 3.4 | 17,000 |

| Handan | 9.2 | 800 | 2.0 | 11,900 |

| Xingtai | 7.1 | 600 | 0.7 | 6,000 |

| Henshui | 4.3 | 500 | 0.4 | 11,800 |

| Outer Jing-Jin-Ji | 31.0 | 600 | 6.5 | 12,500 |

| Jng-Jin-Ji | 109.2 | 500 | 44.6 | 5,900 |

| Population in millions. | ||||

| Jurisdition population from government sources | ||||

| Urban area population from Demographia World Urban Areas | ||||

The Nearby Urban Areas

In addition to Tianjin, other urban areas are expected to gain functions, jobs and residents from Beijing. Baoding, an urban area to the southwest of Beijing is expected to gain hospitals, educational institutions and government offices. Baoding has a population of 1.3 million and is a former capital Hebei, but was displaced by Shijiazhuang in 1967. Shijiazhuang, with a population of 3,4 million, is located in the outer ring of Jing-Jin-Ji.

Langfang is unusual in being a discontinuous municipality, part of which is an enclave surrounded by Beijing and Tianjin (as is Hebei province), and the other part located to the south of both jurisdictions. Langfang is in the path of growth of both Beijing and Tianjin. The urban area of Langfang is still relatively small, with 500,000 residents. The urbanization along the Jingtang Expressway through Langfang nearly reaches the development of Beijing to the northwest and Tianjin to the southeast.

Tangshan is directly north of Tianjin and east of Beijing. Tangshan seems likely to benefit from the dispersion of functions, jobs and residences by virtue of its proximity to both of the megacities. A new high speed rail line has just been announced that would connect Tangshan with Beijing in 30 minutes. Tangshan gained international notoriety in 1976 when it was struck by a devastating earthquake (photo here) that virtually flattened the city and killed at least 240,000 people (estimates of the earthquake death toll reach 800,000). Tangshan has been completely rebuilt, with impressive modern architecture (photograph above, taken from an earthquake memorial), but not appreciated by all. One architectural critic has insensitively bloviated that the new architecture "has been more destructive to Tangshan’s urban history than the great earthquake." Today, Tangshan is an urban area of 2.4 million.

Qinhuangdao, an urban area of 1 million, lies just beyond (northeast of) Tangshan on the way to Shenyang and China’s Dongbei (Manchuria). Qinhuangdao could profit from its well placed seaport.

Transportation Improvements

Important transportation improvements have been announced. There are plans to expand Beijing’s subway, which already has the highest ridership in the world and is second longest (after Shanghai). New suburban train lines will be built and new high speed rail lines will connect the cities within Jing-Jin-Ji that are farther apart. There will be considerable expansion of the already comprehensive expressway system, including Beijing’s seventh ring road, which is to be fully completed by 2017. Already, approximately 400 kilometers have been completed, much of it through the mountains to the west of Beijing.

Decentralizing Beijing

Jing-Jin-Ji would be China’s third megalopolis, joining with the Yangtze Delta (centered on Shanghai) and Pearl River Delta (centered on an axis from Guangzhou to Shenzhen). But Jing-Jin-Ji is substantially different and not so obvious a candidate for integration. Jing-jin-ji’s urban areas are located farther apart than in the Pearl or the Yangtze. Yet its concentration of development is greater, especially in the Beijing core, which provides much of the justification for decentralization.

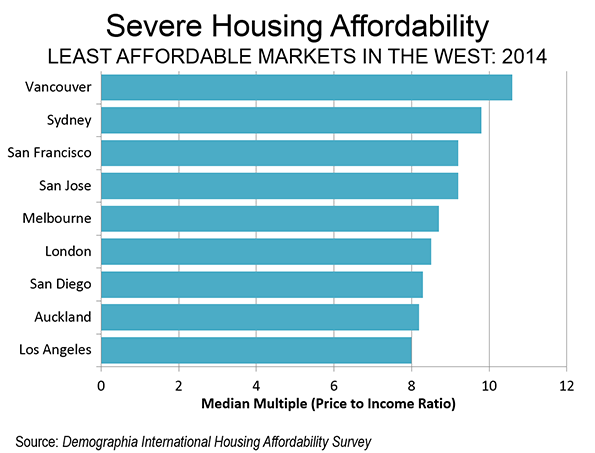

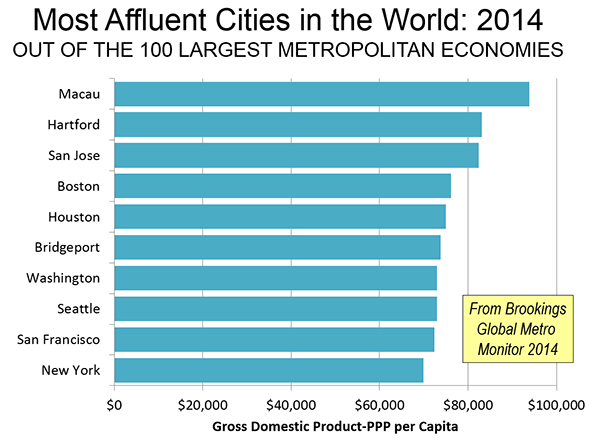

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.

He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Tangshan’s modern architecture, from an earthquake memorial (by author)