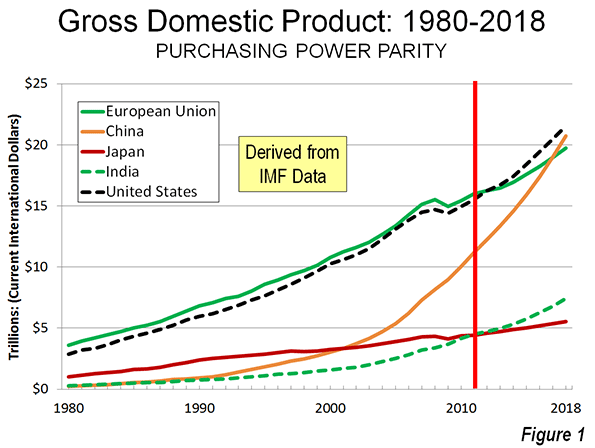

Viewed from a 50-year perspective, the rise of East Asia has been the most significant economic achievement of the past half century. But in many ways, this upward trajectory is slowing, and could even reverse. Simply put, affluence has led many Asians to question its cost, in terms of family and personal life, and is sparking a largely high-end hegira to slower-growing but, perhaps, more pleasant, locales.

The Asian Century may have arrived, but many Asians – disproportionately entrepreneurial, well-educated and familial – are heading elsewhere. In the United States, they have surged past Hispanics as the largest source of immigrants and now account for well over a third of all newcomers. But that’s just the tip of this wave: Recent Gallup surveys reveal that tens of millions more – 40 million from the Indian subcontinent and China alone – would come if they could. This is far more than the 5 million in Mexico who would still like to move here.

For the most part, these highly urbanized Asians are headed to places that may not be exactly pastoral, but are decidedly less-crowded places, either in the suburbs of great cities or, increasing, to sprawling low-density regions such as Houston, Dallas, Charlotte and Phoenix. In large swaths of Los Angeles County’s San Gabriel Valley, parts of the southeastern Orange County as well as the Santa Clara Valley, six cities, including tony San Marino, already are majority Asian, and many, including several in Orange County, are either there or well on the way.

For the most part, these primarily suburban places, widely disdained by the dominant media and academic classes, appear to seem awfully nice to Asian immigrants. Nationwide over the past decade, the Asian population in suburbs grew by almost 2.8 million, or 53 percent, while their numbers expanded in core cities by 770,000, or 28 percent. In Southern California, the shift is even more pronounced: In Los Angeles and Orange counties – the nation’s largest Asian region, the suburbs added roughly five times as many Asians as did the core city. There are now roughly three Asian suburbanites for every core city dweller in our region.

This is not just an American phenomenon. Asians, by far the fastest-growing large ethnic group in Canada, constitute a majority in many Toronto suburbs, like Markham, Brampton, Mississauga and Richmond Hill. The same pattern is seen in areas around Vancouver, such as Richmond, Greater Vancouver, Burnaby and Surrey. Asians, who, following New Zealanders, constitute a majority of newcomers in Australia, also tend to settle in suburbs, particularly newer ones.

It’s most important to understand the reasons these people leave their homelands. Historically, people immigrate from places where there is a perceived lack of opportunity. Yet, many of the Asian countries seeing people leave – places like Singapore, Taiwan and China – have enjoyed consistently higher economic growth rates than any of the destination countries. What these immigrants increasingly understand is that, as their country’s GDP has surged, their quality of life has not and, in many ways, has deteriorated.

These are the sometimes subtle but important things that tend to be ignored by geopoliticians and urban ideologues, attracted by the density and transit-richness of the Asian cities. “Everyday life,” observed the great French historian Fernand Braudel, “consists of the little things one hardly notices in time and space.” And, by these measurements, life in the United States, Canada or Australia is simply better than that in most Asian countries.

In contrast, urban Asia, although rich and often colorful, has become an increasingly difficult place both for everyday life and for families. A nice salary might be satisfying, but is unlikely to be large enough to buy a house or apartment in places like Taipei or Hong Kong, where the cost of even a tiny apartment equals more than twice – adjusted for income – what would be sufficient to purchase a house in Irvine, and four times as much as an even larger residence in Houston, Dallas or Phoenix. Not surprisingly, most Asians in America feel they are living better than their parents, compared with their counterparts at home. Only 12 percent would choose to move back to their home country.

Beyond housing, life in hyperurbanized Asia does not buy much happiness. Prosperous Singapore, for example, is one of the most pessimistic places on the planet, while ultradense South Korea has been ranked as among the least-happy nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, ranking 32nd of 34 members. The country also suffers from among the highest suicide rates in the higher-income world.

This reflects the often-ignored impacts of dense urbanization, including rising obesity, particularly among the young, who get less exercise and spend more time desk-bound. The air is foul, particularly in Beijing, no matter how much money you have. A healthy bank account does not exempt one from emphysema.

Others complain about the dangers of a political system where wealth can always be confiscated by the state; no surprise, then, that a new survey shows roughly half of China’s millionaires are looking to move, primarily to the U.S. or Canada. During 2010-11, the number of Chinese applying for a U.S. investor visa, which requires a $1 million investment in the country, more than tripled, to more than 3,000. Repression of political thought and, particularly, against religion, also ranks as a major cause for leaving the homeland.

The family – the historic centerpiece of cultures from India to Korea – may constitute the biggest victim of the hypercompetitive, ultradense Asian lifestyle. Hong Kong, Singapore and Seoul suffer among the world’s lowest fertility rates, with rates around 1. Meanwhile, Shanghai’s fertility rate has fallen to 0.7, among the lowest ever reported, well below China’s “one child” mandate and barely one-third the rate required simply to replace the current population. Due largely to crowding and high housing prices, 45 percent of couples in Hong Kong say they have given up having children.

For those who do want to start a family, it increasingly makes sense to immigrate. This is evident in rising emigration from China’s cities, Hong Kong and Singapore, where roughly one in 10 citizens now lives abroad, often in lower-density communities in Australia, Canada and the United States.

The nature of those immigrating is critically important. We are long past the days when the average Asian migrant is a physical laborer or a small-scale merchant. Now, the more typical newcomer is a student or a highly qualified professional. In Australia, Asians, notably from India, China and Taiwan, make up the vast majority of immigrants who qualify for entry under skills-oriented criteria.

This pattern also can be seen in the United States. Asians now constitute a majority of workers in Silicon Valley. They also tend to concentrate in what may be best described as the country’s largely suburban nerdistans – magnets for high-tech workers – places like Plano, Texas, Bellevue, Wash., Irvine and large swaths of Santa Clara County.

Does all this mean Asia is about to experience a precipitous decline? Not at all. But it is also increasingly clear that the dense model of development adopted on much of that continent – exacerbated by a mass movement to cities – is not, in a larger social sense, truly sustainable. Societies that become difficult for families, and exact too much stress on their residents, are destined to suffer maladies from ultrarapid aging, shrinking workforces and a host of psychological maladies.

These strains will become more evident over time. Already, most Asian societies, from Japan and China to Singapore and Taiwan, are experiencing less growth, linked in part to financial pressures from a rapidly aging society. The economic motivations for staying in Asia will likely decline, accelerating the flight both of financial and, more importantly, human capital.

Every society relies on the resourcefulness of its people, particularly the young. The loss of skilled individuals and, especially, families suggests we may have already witnessed the peak of the half-century-long Asian ascendency, well before the American era has even come to its oft-predicted demise.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared at The Orange County Register.

Singapore skyline photo by Bigstockphoto.com.