This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism titled “The Texas Way of Urbanism“. Download the entire report here.

Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW) has started the 21st century with a bang. Like the other major metro areas in Texas, the DFW area has grown far faster than most large U.S. cities: 35 percent population growth for the DFW metro area between 2000 and 2014, compared to an average growth rate of 21 percent for America’s top 40 cities. GDP per capita growth in the metro area has also handily outpaced the average of its “Top 40” peers as well, 46 percent versus 39 percent.

It’s not just numbers, but also strong qualitative growth. Dallas-Fort Worth has consistently ranked as one of the premier destinations for corporate relocations and facilities growth. It has built on its central location and efficient transportation infrastructure to become ever more pivotal to the nation’s commerce across a wide variety of industries. The DFW area just reached the milestone of housing 7 million people, making it the fourth largest metropolitan area in the country. Looking ahead, DFW is increasingly challenging Chicago, currently number three at 9.6 million, as the leading business center in the interior of the United States. Texas state and local authorities project that the DFW population will reach 10.5 million by 2040. This economic and demographic success has arguably positioned greater Dallas as the next great American metropolis.

Why has DFW grown so fast, particularly since 2000? How does the growth of DFW fit into the larger story of how the system of American cities has evolved in recent years? And how has the type of growth and urbanism which characterizes the leading cities in Texas contributed to the success of the DFW area?

DFW has gotten many things right, particularly with respect to taxes, land use policies, airports, and other infrastructure. But it has also benefited enormously from a confluence of long-term economic changes transforming the whole landscape of urban America. To sum up our argument, the DFW area has grown so fast because it has proved a more hospitable environment to middle-income individuals and families than most other large U.S. cities in recent years.

Who’s Coming?

The field of urban economics starts from the premise that people can move from one city to another relatively easily, so the configuration of people across cities at any moment in time reflects what urban economists call a “spatial equilibrium,” that is, people are where they want to be and cannot readily improve their lives by moving elsewhere. Urban economists go on to break down the considerations that people take into account in deciding where to live into three categories:

• Productivity – which drives how much people can earn in a given place

• Amenities – which are the natural or man-made features which make a city a desirable place to live

• Costs – which range from housing and other direct costs of living to traffic congestion, long commutes, and other ills associated with high urban density

A large shift in population from one group of cities to another over a period of time prompts the question of what’s changed during the period, and specifically how the relative configuration of productivity, amenities, and costs has evolved.

We put the data on DFW in comparative perspective, looking at the top 40 metropolitan statistical areas, as the U.S. Census calls them. We also divide this group into the top 20 “coastal” cities and the top 20 “interior” cities, since one of the big 21st century demographic stories in the United States has been a large migration of people from the largest coastal cities to somewhat smaller interior cities. This migration has reversed the dominant trend of the 20th century – which saw large migrations to the coasts, especially California – and provides a larger context for the recent growth of DFW and other Texas metro areas.

Since the DFW region has been the recipient of tremendous inbound net migration, one question to address is who’s been moving to the area. Demographic data suggests three general patterns. Inbound migrants to the area:

• Come from everywhere, to a greater degree than has been the case in most other large cities

• Disproportionately include young families with children

• Are less educated, on average, relative to the Top 40 cities

First, DFW has been exceptionally successful in attracting both domestic and international migrants. Of DFW’s 35 percent population growth since 2000, 10 percent is from net migration from elsewhere in the United States and 8 percent consists of net immigration from abroad — in both cases well above the Top 40 city average (the rest of DFW’s growth is from natural population growth – more births than deaths). This pattern is unusual. The biggest beneficiaries of net domestic migration, adjusted for their size, are generally smaller, relatively inexpensive interior cities like Nashville, San Antonio, and Phoenix, which have tended to attract disproportionately small immigration by foreign-born people. Meanwhile, the largest coastal cities have attracted more than their share of foreign-born immigrants, while mostly losing native-born people to net outbound migration.

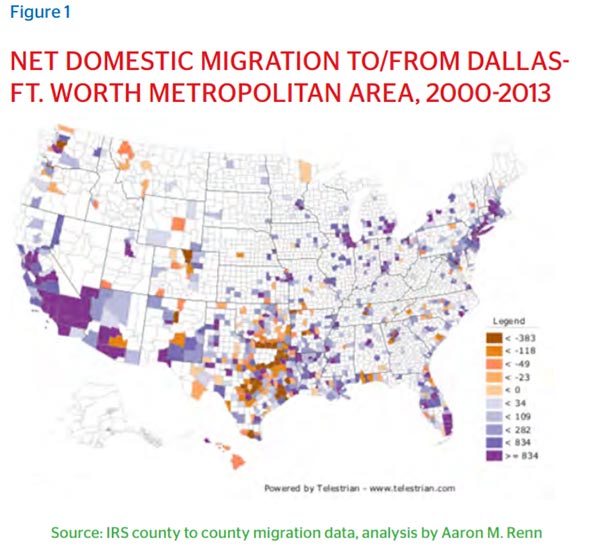

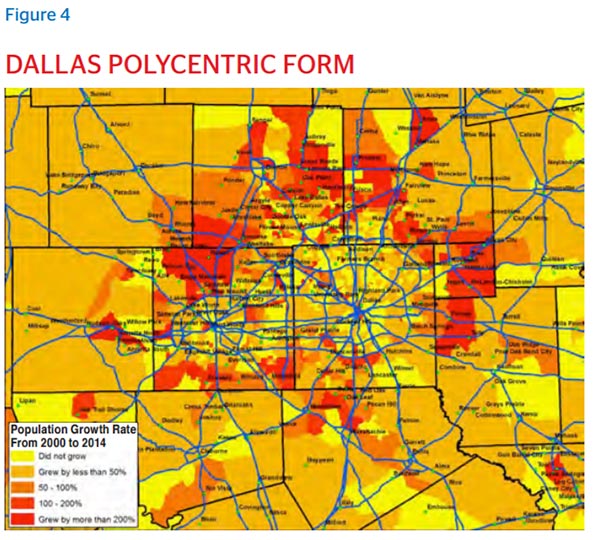

Figure 1 illustrates the largest sources of inbound domestic migration to DFW, as well as the largest destinations for outbound migration, by county. The largest source of inbound domestic migration is Southern California, followed by the New York-to-Boston corridor, Chicago, and, to a lesser extent, Midwestern cities like Kansas City and St. Louis. Mexico, India, and China are the most important sources of international migration to the area.

A second pattern is that migrants to DFW disproportionately include young families with children. DFW, along with Houston, has the highest proportion of under-18 people in its population of any Top 40 metro area. Big coastal cities like New York, San Francisco, and Seattle, meanwhile, continue to do reasonably well in attracting single, well-educated Millennials, even as married people with children move out in droves.

Third, migrants to the area are less educated, on average, relative to the Top 40 average. DFW ranks somewhat behind the Top 40 average in the share of 25-34 year-olds with a Bachelor’s degree or higher (32.7 percent versus 37.6 percent in 2014) and the share of the total population with an advanced degree (9.4 percent versus 11.8 percent). All major metro areas have seen these educational attainment rates increase since 2000, but DFW and other Texas cities have experienced smaller-than-average growth, in large part because the population of inbound migrants ranks lower than average in education levels. The metro areas which have experienced the greatest increases in education levels are generally the ones with already high levels in 2000, mostly in the Northeast and on the West Coast. That said, although DFW’s growth in the share of people with degrees has been slower than some other cities, its total number of people with a Bachelor’s degree or higher has grown by more than 500,000 since 2000 – fourth highest among all metro areas — simply because the region has added so many people.

Towards an Explanation

Traditional explanations for the relative success of DFW typically focus on its warm weather, its central location, its vast airport (the 9th busiest in the world), its transportation infrastructure, and its business-friendly political climate. These assets are very real, but they do not do a very good job of explaining the city’s unusual growth since 2000, for two reasons. One is that a number of other interior cities have similar advantages but have grown at more pedestrian rates. The other reason is that DFW already had these assets in 2000 and indeed well before then. To explain the dramatic population shifts since 2000, one must focus on what has changed over the last 16 years.

Productivity

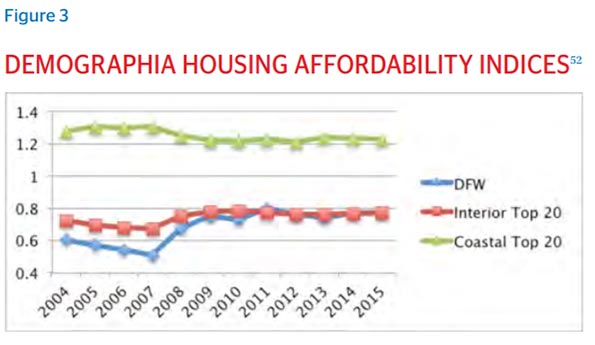

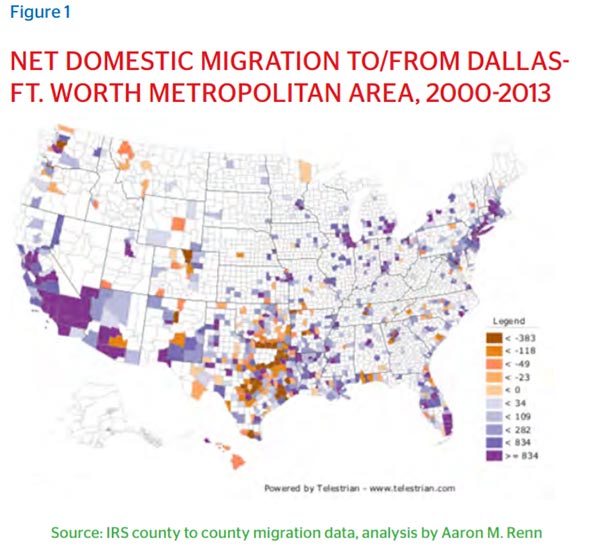

The data on relative productivity, amenities, and urban costs across America’s top 40 cities point to a great deal of change. Consider, first of all, productivity. Average personal income per capita in DFW is very close to the Top 40 average, and has also experienced nearly identical growth since 2000 (Table 1). However, it has moderately outperformed the “Interior” Top 20 in income growth, and currently has higher average income levels than most interior peers. Perhaps most relevant are differences across cities for the same occupational category, since people deciding where to live and work are presumably most interested in comparisons within their own occupation.

Productivity in DFW is higher than that of the Interior Top 20 average in finance and business operations and computer operations, two of the fields most heavily represented in DFW. Productivity growth in DFW has outpaced the Interior Top 20 average in finance and business operations since 2000, though not in computer operations. In sum, the data suggests that DFW has performed modestly ahead of most Interior Top 20 metro areas in productivity growth, though not ahead of the Coastal Top 20.

Population and productivity growth feed off each other. Urban economists have regularly found that large cities offer residents opportunities to be more productive and earn higher wages than they could in smaller, less dense locations. Generally speaking high population growth tends to promote high productivity growth. High productivity and wages, in turn, attract more people. So, DFW’s productivity growth is undoubtedly a consequence, in part, of the area’s rapid population expansion.

But there are deeper reasons why it has achieved above average productivity growth, relative to other interior cities. One is the long-term trend towards increasing geographic concentration of service-sector activities, a global trend that runs counter to the rising geographic dispersion of manufacturing activity. DFW has been fortunate to see financial services and professional- business services, its two fields of greatest comparative advantage, grow from 30.2 percent to 31.9 percent of the U.S. economy between 2000 and 2014, and become more geographically concentrated in a handful of large urban centers, including its own. Specialist healthcare services have also become increasingly concentrated in major medical centers, another trend that has benefited the region.

Another factor lies in the diversity of DFW’s industrial base. An insight from urban economics is that diversity of industries and employment turns out to be good for productivity growth in modern cities. Industrial concentration is helpful if it is in the right industries, as in Silicon Valley, at least for today, but not if it is in (say) automobiles, as in Detroit, or steel, as in Pittsburgh. But diversity provides more than a hedge against decline in a city’s primary job engine. The author Jane Jacobs famously argued that large, industrially diverse cities promote cross-fertilization of ideas and make residents more productive on average. Research by the urban economist Edward Glaeser of Harvard and others has confirmed this relationship in U.S. data in recent decades.

DFW has reaped the fruits of having an exceptionally diverse economy. According to comparisons of industrial diversity published by Moody’s, the area economy’s diversity index has grown from 0.72 in 2000 to 0.80 in 2013 (with the aggregate U.S. economy normalized to an index value of 1.00). Over the same period, the diversity index for the Interior Top 20 rose only from 0.69 to 0.71 on average, while the Coastal Top 20’s average index value increased from 0.52 to 0.58. New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle, all relatively concentrated cities in terms of their employment base, have generally remained as concentrated as ever over the last 16 years. Site Selection magazine has found that DFW is among the top five “most competitive” cities in 10 of 12 sectors. DFW is first in business and financial services as well as in food and beverages, second in communications and in transportation, and third in aerospace. DFW, moreover, hosts multiple large employers in each of these industries, another source of urban success in recent decades.

DFW is growing its base of innovative activities and startups along with the rest of its economy. But innovation is not as convincing an explanation of why the region is growing so much faster than others. DFW is a solid performer but in the middle of the pack in terms of innovativeness, compared to the average Top 40 city. DFW ranks 21st of the Top 40 in patents per employed person. It is also roughly average in terms of the share of metro area jobs in “creative” or “STEM” occupations and in venture capital investments per capita. Similarly, DFW is 15th among the Top 40 in startup activity, as measured by a Kauffman Foundation index, and is just below the Top 40 average in the number of startups per capita and in growth in the number of business establishments, according to U.S. Government data. DFW does have a tremendous amount of innovative and entrepreneurial activity – but so do all large, successful cities. And while DFW is friendly to innovation such as high-tech startups, one of its virtues is its friendliness to a broad spectrum of other activities as well. So innovation is not the major driver of the region’s outsized growth rate.

Amenities

Turning to amenities, any effort to rank cities according to their desirability as a place to live is inherently subjective. Still, virtually all rankings find that DFW has good, but not standout, amenities. DFW ranks 11th of the Top 40 cities in Mercer’s 2015 “quality of life” rankings, 17th in a similar ranking published by U.S. News and World Report in 2016, and 8th in a ranking devised by economists Michael Cox and Richard Alm of SMU’s Cox School of Business.

These rankings tend to evolve slowly, and there is little evidence that DFW has moved up very much in the rankings since 2000. DFW has built out very distinguished arts facilities in both the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, as well as a premiere football stadium, during the past 16 years. But again, large metro areas typically feature top-notch amenities. What would have been more remarkable is if DFW had failed to develop amenities in keeping with its large size, rapid growth, and new economic stature.

The Key Advantage: Costs

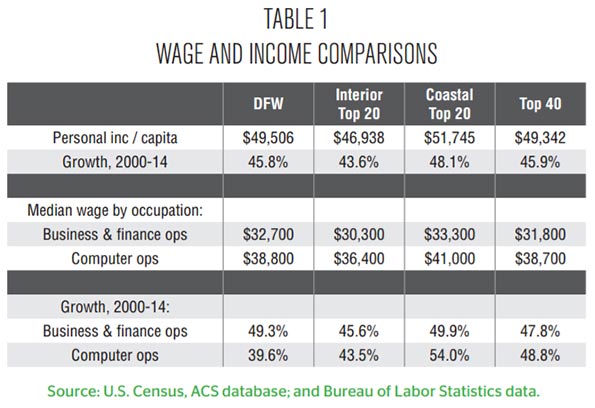

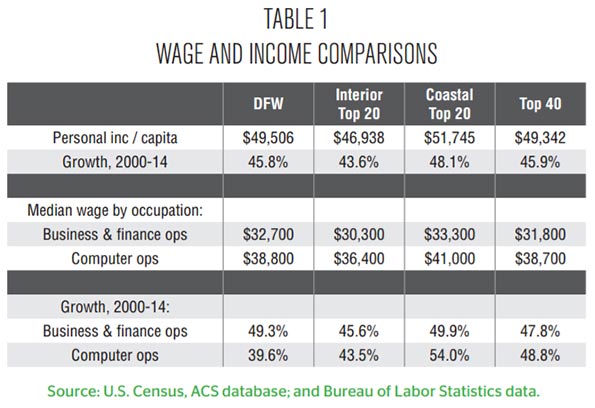

Without question, the most significant divergence between DFW and the major coastal cities has been in the cost of living and doing business. This divergence is most obvious in the cost of housing. Between 2000 and 2012, the Case-Shiller house price indices for the 11 cities among the Coastal Top 20 for which Case-Shiller indices exist rose an average of 41 percent (Figure 2). The average increase for the seven cities among the Interior Top 20 for which indices exist was 6 percent, while DFW prices appreciated 13 percent. So during that time, coastal city housing prices went up far faster than those in DFW or other interior cities.

But this trend changed starting around 2012. Over the next three years, DFW prices increased by the same amount as the average of the coastal cities – 39 percent. Other interior cities are only slightly behind, at an average of 35 percent.

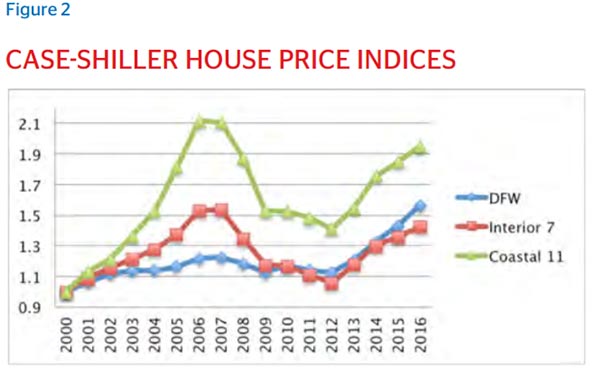

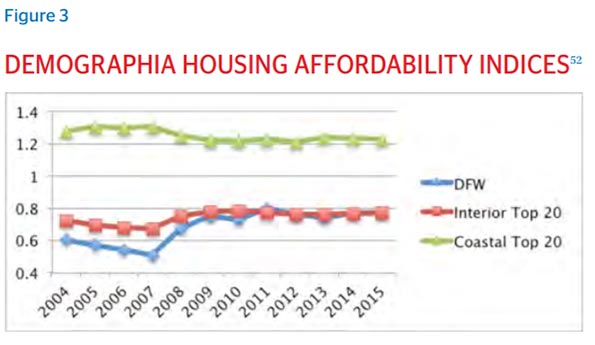

The research organization Demographia, which measures housing affordability across U.S. cities on a comparable basis, arrives at similar results. Based on Demographia indices, DFW housing costs declined from 60 percent of the Top 40 average in 2004 to 51 percent in 2007, then went up to 76 percent in 2012 and 77 percent of the U.S. level by 2015 (Figure 3). Average housing costs in the Top 20 interior cities fell from 72 percent in 2004 to 67 percent in 2007, then went up to 77 percent by 2015. In the coastal Top 20, meanwhile, housing costs increased from 128 percent of the U.S. average level in 2004 to 131 percent in 2007, then fell back slightly to 123 percent by 2015.

These and other measures of housing affordability all point to the same conclusions: DFW began the century with a moderate-sized edge relative to other interior cities and a very large advantage compared to the large coastal cities, increased its advantage over the next six years or so, then began to give up some of its enormous edge over the last decade. The region still has a large cost advantage over the coasts, but not as large as it used to be, despite well publicized run-ups in the cost of coastal housing.

A look at home price listings on Zillow confirms that the substantial housing cost advantage Dallas has enjoyed relative to other large cities is not a result of comparing “apples to oranges.” As of April 2016, asking prices for condos in the thriving Uptown area of Dallas are some 13 percent below prices for highly comparable condos near Chicago’s “Magnificent Mile” and 62 percent below San Francisco’s Pacific Heights. Asking prices in DFW’s prosperous suburbs of Frisco and Southlake are 39 percent below those in Chicago’s suburb of Highland Park and 83 percent below those in the Bay Area’s Cupertino and Hillsborough.

Comparisons of other categories of urban costs tell a similar story. Office rent levels increased in DFW relative to the average Interior Top 20 city between 2000 and 2014, but they rose much less than rents in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Miami. Average daily commute times in DFW were close to the Top 40 average as of 2014, but they did not go up between 2000 and 2014. In the large coastal cities, as well as Chicago, by contrast, they were worse than average in 2000, and they have lengthened considerably in the years since. Business taxes plunged in DFW relative to the Coastal Top 20 average between 2000 and 2014, and fell somewhat relative to the average Interior Top 20 city as well. The idea that Dallas offers significant cost-of-doing business advantages relative to Chicago and the largest coastal cities appears frequently in media coverage of corporate relocation decisions.

Origins of DFW’s Edge

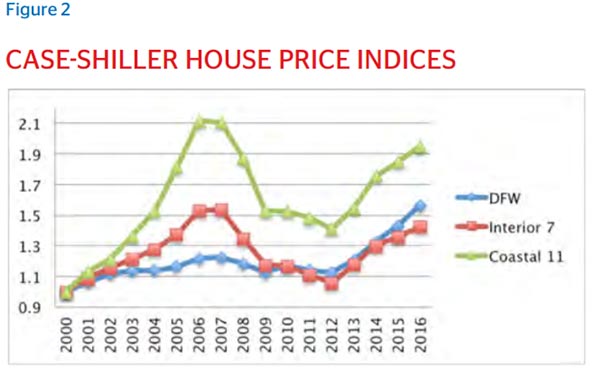

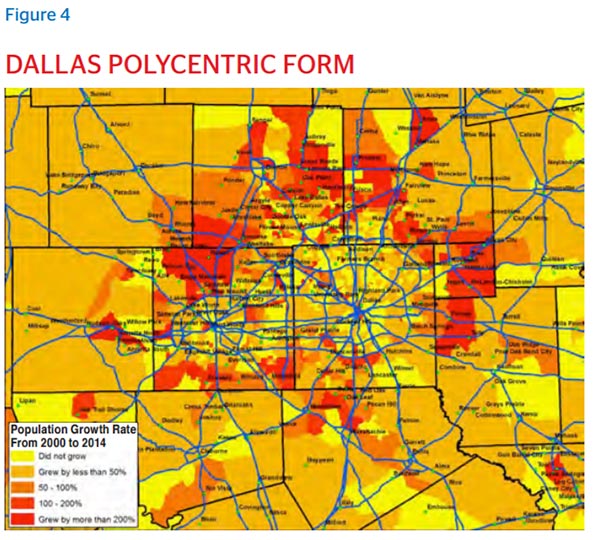

DFW’s sizable cost advantage relative to most other large U.S. cities stems both from its distinctive urban geography and from large and growing divergences in public policies. The geography of the region has always been unusually polycentric, for reasons partly rooted in the city’s history. The city of Dallas grew up primarily not as an oil town but rather as an inland cotton trading and transportation center, while Fort Worth, known as “Cowtown,” developed as a ranching hub. This history helps explain the area’s economic diversity today. However, the DFW area only emerged as a major metro area with the Interstate Highway Act of 1956 and the opening of DFW International Airport in 1974. Relative to most Top 40 cities, the core municipalities of Dallas and Fort Worth had unusually small downtown districts as they entered the postwar age and a vast expanse of countryside into which to expand

Today, DFW is characterized by numerous, widely distributed centers to which people travel to work and play. The traditional central business districts in the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth house 11 and 3 percent of the metro area’s office space, respectively, compared to ratios between 30 and 50 percent in cities like Boston, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, and Seattle, and more than 55 percent in Chicago. Seventeen high-density mixed-use centers away from the two CBDs have been developed in DFW over the last two decades, a pattern now spurring imitation in older cities whose suburbs have generally been known as sleepy bedroom communities. People moving in from California, India, and China are settling disproportionately in DFW’s booming northern suburbs, especially in relatively distant communities with marquee school districts and attractive town centers like Frisco, Allen, and McKinney. Migrants from New York and Mexico, by contrast, disproportionately settle in the city of Dallas proper.

Contrary to the widespread view that well-educated Millennials prefer living in densely populated enclaves in the central city, a variety of national, as well as local studies, have shown that Millennials turn out to have conventional housing preferences once they get older and particularly when they have children. So, a large and growing share of them live and work relatively far from central business districts. This plays to DFW’s strengths as a polycentric region. While urban areas such as the central core of Dallas, particularly its Uptown area, have thrived, many other nodes have too. This pattern of distributed geography has almost surely helped to keep housing and other urban costs lower than they would otherwise be given the metro area’s size and productivity, since proximity to the CBD or other employment centers is inherently less critical than it is in more traditional “monocentric” metro areas. It also provides a variety of different environments catering to diverse residential preferences.

Dallas-Ft. Worth vs. Chicago

Dallas-Ft. Worth and Chicago, America’s largest two interior metro areas, make an interesting comparison. In some respects, they are very similar: diversified economies; major hub airports and important transportation infrastructure; very diverse populations in a statistical dead heat in their foreign-born population share (DFW at 17.9 percent and Chicago at 17.6 percent).

But, in other ways, they present an especially stark contrast to one another. Chicago has a dense CBD with numerous corporate head offices and real estate costs far above DFW levels. The metro area’s employment base disproportionately consists of senior management people and professionals who work closely with them in fields like marketing and law. On the other hand, Chicago is severely under-represented in many of the medium-skilled but well-paid occupations which figure most prominently in DFW, like credit analysts, insurance appraisers, systems analysts, database administrators, and other “back-office” jobs. Chicago has recently scored just ahead of DFW in attracting corporate relocations, but, according to Chicago press coverage, the typical relocation has often amounted to moving the head office into the CBD with (say) 300 employees. By contrast, typical corporate expansions in the DFW area – such as recent moves by Toyota, State Farm, and Liberty Mutual – have generally consisted of building major headquarters or back-office centers in DFW’s northern suburbs and creating more than 1,000 jobs.

The net result is that while Chicago’s CBD and select suburbs are performing well, the DFW region is far outpacing the Chicago area in growth. DFW’s job growth from 2000 to 2015 was 21.1 percent, compared with Chicagoland’s 0.4 percent. In the professional and business services sector in which both cities specialize, DFW ranked as the 5th best of the top 40 metros as a place to do business according to a 2016 New Geography survey, while Chicago ranked 27th. DFW’s ranking improved since the previous survey, while Chicago’s declined.

Since 2000, the DFW metro area’s population has grown 35 percent, compared to 5 percent growth in the Chicago area. And from 2000 to 2014, Dallas per capita incomes increased by 45.8 percent, compared to 41.6 percent in Chicago.

What’s more, the urban core of Dallas has also seen something of a development boom of its own. While it’s not as large as Chicago’s Loop, areas like Uptown provide an urban environment for those who prefer it. And they do so within an overall region that is both affordable and thriving economically.

Public policy has also played an important role in containing urban costs in DFW. Based on a new index developed by Dean Stansel of SMU’s Cox School of Business which focuses on government spending, taxes, and labor market regulation, the DFW metro area ranks fourth among the top 40 cities in “economic freedom,” behind only Tampa, Jacksonville, and Nashville – all growing cities – but far ahead of all the largest coastal cities. Relatively low taxes have not imposed any evident cost on DFW’s public finances. Although bond rating agencies downgraded the city of Dallas in 2015 due to its underfunded pension liabilities (a challenge bedeviling many American cities), Dallas and its surrounding towns enjoy better credit ratings than all but a handful of U.S. cities.

Critics of Texas urban growth argue that a low tax burden has an undesirable flip side, in the form of heightened poverty rates, inequality, and poor education systems. It is true that DFW has a large pocket of entrenched poverty in the southern sector of the city of Dallas and in several largely African-American suburbs to the south. That said, income inequality in DFW as measured by the so-called “Gini coefficient” was exactly in line with the average for the top 40 metro areas in 2013. DFW’s inequality index was well below that of Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, as well as several cities that are slightly smaller than DFW like Atlanta, Boston, and Philadelphia. Income inequality has increased in virtually all U.S. cities this century, but it has grown at a less-than-average rate in DFW and a greater-than-average rate in the big coastal metro areas.

A prominent recent study of the American middle class by the Pew Research Center arrived at a similar result. According to the Pew study, the “middle class” share of the population declined between 2000 and 2014 in all of America’s 40 largest metro areas, but it declined less in DFW than in most metro areas. In absolute terms, the middle-class population share in DFW was slightly below the Top 40 average in 2014, but considerably higher than in New York, Boston, Washington, Los Angeles, or San Francisco.

As for education, the city of Dallas school district performs moderately below average among the Top 40, though roughly in line with Chicago and ahead of several high-tax cities like Baltimore and Cleveland, according to the “Mayors’ Report Card on Education.” Districts in northern suburbs like Plano perform much better, though not quite as well as comparable districts in some of the “best-educated” metro areas, in towns like Northbrook/Glenview (outside Chicago), Weston (outside Boston), or Cupertino (outside San Francisco). Poorly performing school systems undoubtedly constitute a major challenge for the DFW area as they do for all large U.S. cities, but the evidence does not suggest that DFW has so far suffered from either unusually poor public services or unusually high inequality as a result of its relatively low tax rates. Still, the increasing importance of human capital in the success of the world’s leading cities suggests that improving education is essential to ensure DFW’s future growth.

In addition to tax policy, relatively unrestrictive land use regulations have played a crucial role in containing urban costs as DFW and other Texas cities have grown. Wendell Cox of Demographia has demonstrated a close relationship between land use policies and housing affordability across cities in the U.S. and other countries. Based on an index of land use regulation published by the Wharton School of Business, DFW has the fifth most relaxed regulatory environment among the top 40 cities.

Meanwhile, studies by urban economists show that a number of the largest coastal cities have tightened already-restrictive land regulations further in recent years. Such policies have driven up housing prices and caused a decline in migration to these cities, which has resulted in increased “sorting” because the highest-skilled young people can justify living in cities like New York and San Francisco but medium-skilled people, or those without access to family funds, cannot.

To some, the big coastal cities are inadvertently turning themselves into de facto gated communities for the very rich and the people who take care of their various needs. Jason Furman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors has started to criticize the tight land use regulations increasingly pursued by many local governments along similar lines, saying that “excessive or unnecessary land use or zoning regulations” can give “exceptional returns to entrenched interests at the expense of everyone else.” DFW is attracting people, but it’s also benefiting as coastal cities repel them.

Sustaining the Middle Class Dream

Summing up, the rapid growth of the DFW area since 2000 is closely connected with pervasive changes in the whole system of U.S. cities. American cities have grown more industrially diverse, but also further specialized in terms of the kinds of people who gravitate to them. Large, high-density cities foster greater innovation and productivity growth than other places, but many of the densest, most productive cities are increasingly unaffordable for all but the most highly skilled. DFW, on the other hand, presents a broader spectrum of people a winning package – moderately higher wages than they can make in most other interior cities, a diverse range of growing industries, and drastically lower urban costs than what people face in the major coastal cities. Like other Texas cities, DFW attracts enterprises aiming to run competitive, labor-intensive operations in a business-friendly environment, and families striving to attain a middle-class lifestyle with a medium-sized paycheck. DFW has grown as fast as it has because the middle-class “American Dream” is alive and well there, at least relative to most other large cities.

Looking to the future, this analysis highlights several significant challenges to the DFW growth model. The metro area’s luck might change, if, for instance, increased automation or offshoring reverses the growth of the last couple decades in the kinds of back-office operations in which DFW currently excels. Education and workforce readiness issues might start to constrain the city’s growth. Most important, the divergence in urban costs across metro areas which so shaped the landscape of American cities during the first decade of this century has given way to mild convergence, as housing and other urban costs in high-growth cities like DFW and Austin have begun to spiral upwards as fast as in the large coastal cities, and even faster in some comparisons. And, substantial gaps are opening up between DFW and cheaper interior cities like Kansas City and Columbus in terms of the costs of living and doing business, raising the possibility that a new wave of cities which don’t yet receive much attention may step up as serious challengers.

These issues point to larger questions for the region. The breakneck growth of the DFW area is, after all, an experiment, testing whether a city so geographically dispersed, so polycentric, and so automobile-dependent can grow from 7 to 10 million people without generating unmanageable increases in congestion and other urban costs. Some suggest that increased residential density might mitigate some of these costs, and indeed DFW is experimenting with increased density in the Uptown area and even in suburban Plano. However, the literature on urban economics suggests that large migration from one city to another is likely to reduce urban costs in the former city and raise them in the latter to the point at which net migration stops. It is impossible to tell how close the system of U.S. cities is to this point.

The other big question for DFW, usually unvoiced, is whether growing to 10 million is a good thing. If doing so means following in the footsteps of the largest cities in the Northeast and on the West Coast, Dallasites may start to have their doubts. But this would be a problem of success. Managing such rapid growth in jobs and population is a challenge most other regions would dearly love to have.

Klaus Desmet is the Altshuler Centennial Interdisciplinary Professor of Cities, Regions and Globalization at Southern Methodist University and a Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research in London. He holds an MSc in Business and Engineering from the Université catholique de Louvain and a PhD in Economics from Stanford University. He previously was professor at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. His research focuses on regional economics, urban economics, international trade, and economic growth. He has published in leading academic journals such as the American Economic Review, the Journal of Political Economy and the Journal of Development Economics, and his work has been covered by the BBC, The Economist and The Times.

Cullum Clark is the President of Prothro Clark Company, a Dallas family investment firm, and is also a doctoral student in the Economics Department at SMU. At Prothro Clark Company, Cullum oversees an investment program comprising public equities, bonds, real estate, hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital. His research in economics focuses on monetary policy, financial economics, economic history, and economic geography.

Top photo by: fcn80 (http://www.flickr.com/photos/fcn80/105065297/) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons