Black population changes in various cities have been one of the few pieces of the latest Census to receive significant media coverage. The New York Times, for example, noted that many blacks have returned to the South nationally and particularly from New York City. The overall narrative has been one of a “reverse Great Migration.” But while many northern cities did see anemic growth or even losses in black population, and many southern cities saw their black population surge, the real story actually extends well beyond the notion of a monolithic return to the South.

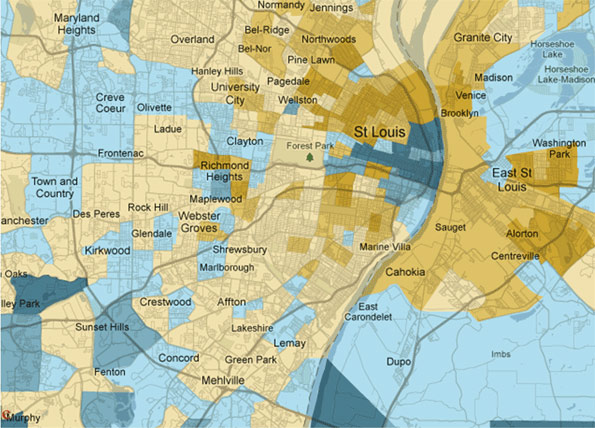

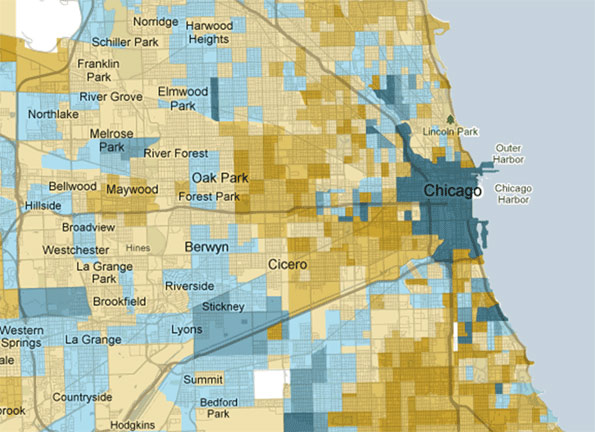

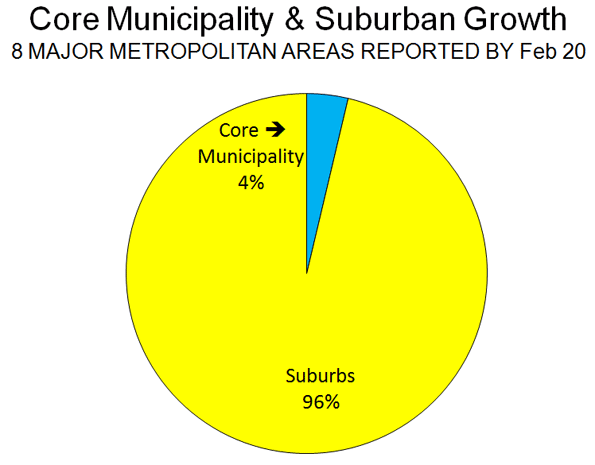

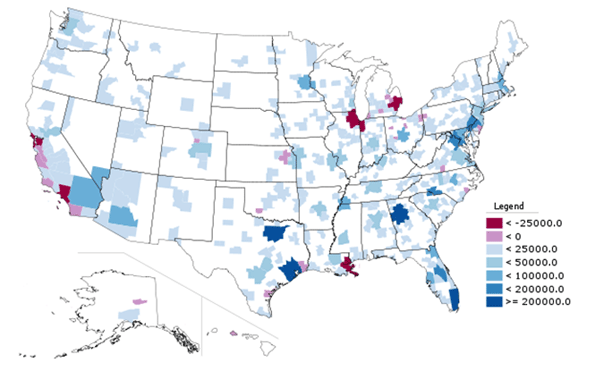

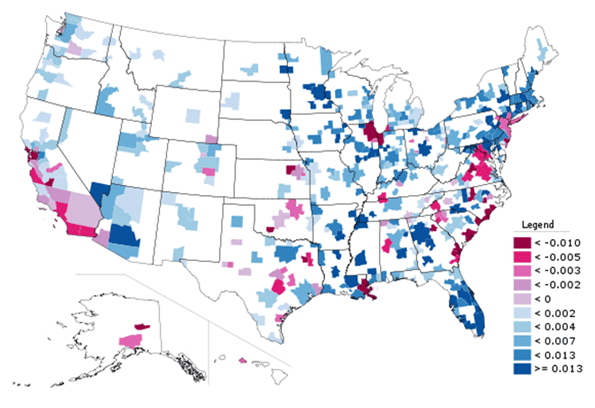

The map below, showing total growth in Black Only population from 2000 to 2010, indeed shows that northern and west coast cities had low or even negative growth while various southern cities boomed.

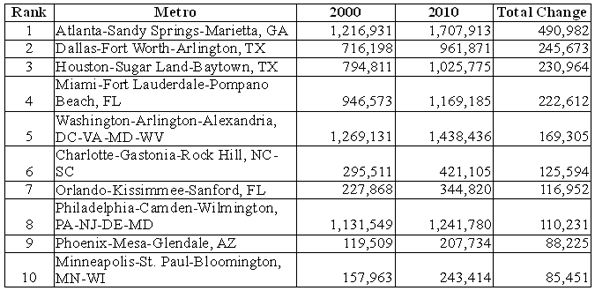

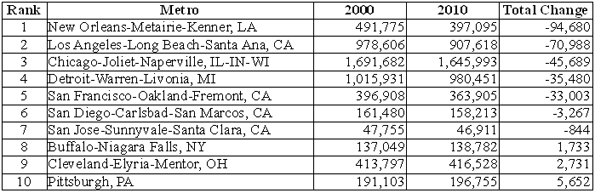

Here is a list of the top ten metro areas (among those with more than a million total people) for black population growth:

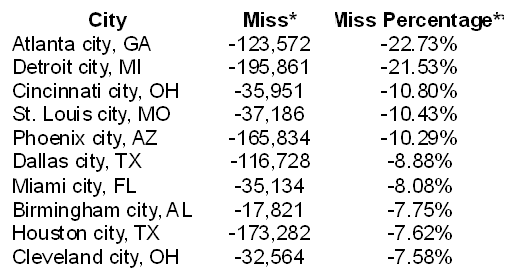

And here are the bottom ten (among those with more than one million people):

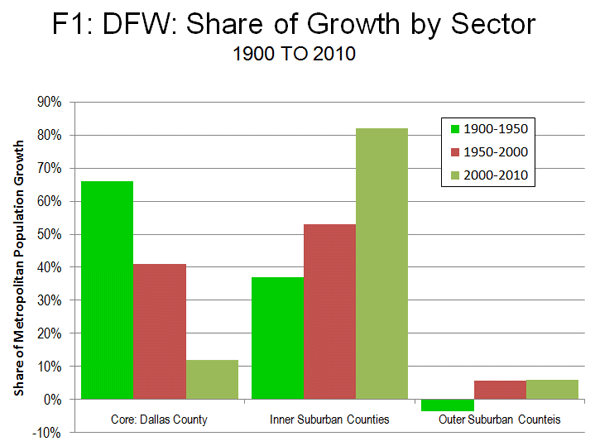

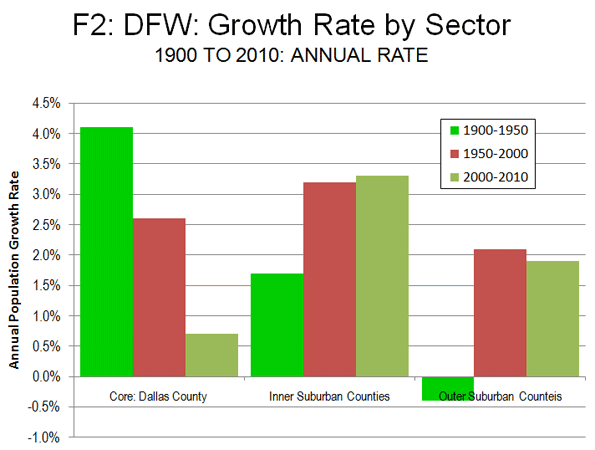

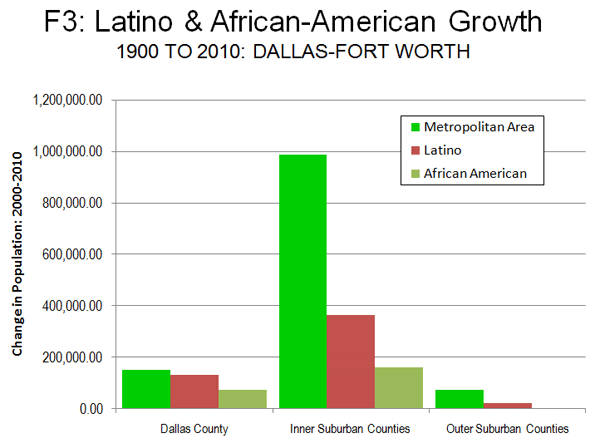

Of course, looking at total population numbers can mislead. Some cities grew slowly or lost people as a whole while others boomed. With Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta all adding over a million people each, it’s no surprise these regions added lots of blacks. Working and middle class African-Americans likely shared many of the same motivations to move to these cities – such as lower housing prices – as Americans of other ethnicities. In that light, a look at change in black population share (the percentage of the population that is black) provides additional perspective:

Here we see not a single-minded return to the South, but a complex mixture of shrinking and growing regions in various parts of the country. This includes some surprising places, like Minneapolis-St. Paul, which was one of the top ten metros in the country for total black population growth, and also saw its black population share grow strongly. Now the Twin Cities, along with Columbus, Ohio, another strong performer, are two of the top destination for African immigrants from Somalia and elsewhere, which doubtless accounts for part of that strong growth. But anecdotal reports indicate that they are also benefitting from Chicago’s expanding black diaspora, along with places like Indianapolis and various Downstate metros.

Atlanta, well known as America’s premier metro area for blacks, continued to dominate the charts. Not only far and away the leader in adding raw numbers of blacks, the African-American share also grew share strongly too. Charlotte is also clearly emerging as another key black population hub, ranking #6 in America for total black population growth, which is impressive for a smaller city, and adding nearly two percentage points in black population share. It grew its black population much faster than other fast growing small cities like Raleigh or Nashville, and added share at more than three times as fast.

By contrast, Houston, which grew total black population significantly, had a much lower share gain. Austin, one of America’s fastest growing metros, added only 28,000 blacks and actually lost black population share. And Washington, DC, despite being a traditional black population and cultural hub, also lost black population share regionally as gentrification in the District resulted in its loss of its black majority for the first time in decades, according to the Brookings Institution.

So even among rapidly growing metro areas in the South, the appeal to black population is selective, favoring places like Atlanta, Charlotte, Florida cities, and even slower growing cities along the length of the Mississippi River like Memphis. Even some cities in the North are retaining their allure to blacks as well. Less favored or even out of favor are metros like DC, Dallas, and Houston as well as cities such as Charleston and Savannah along the southeast coast.

Slow or negative black population growth is particularly concentrated in traditional tier one “global cities”, as well as those facing economic or other hardship like Detroit, Cleveland, and immediate post-Katrina New Orleans.

The latter may be understandable – whites have been leaving these regions as well – but the former is quite troubling. The global city model, focused on high end and creative services, is supposedly the bright and shining savior of American urbanism. Indeed, it’s hard to find a city that doesn’t have some aspect of that as a core plank in its civic strategy. Yet the cities that have been most focused at promoting this notion – such as New York, San Francisco, and Chicago – are generally those disproportionately driving blacks away. The reasons for this aren’t clear, but the high and increasing cost of living in those places seems like one logical explanation.

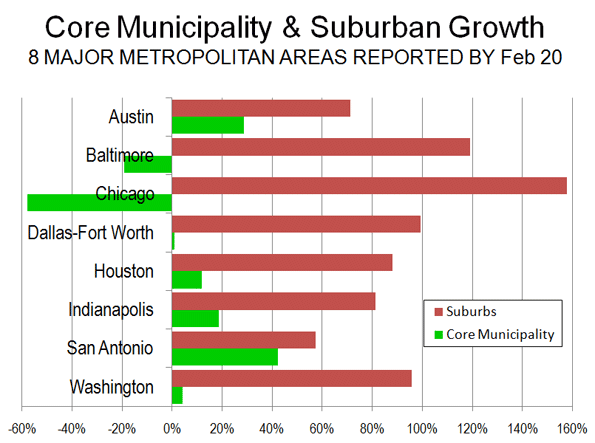

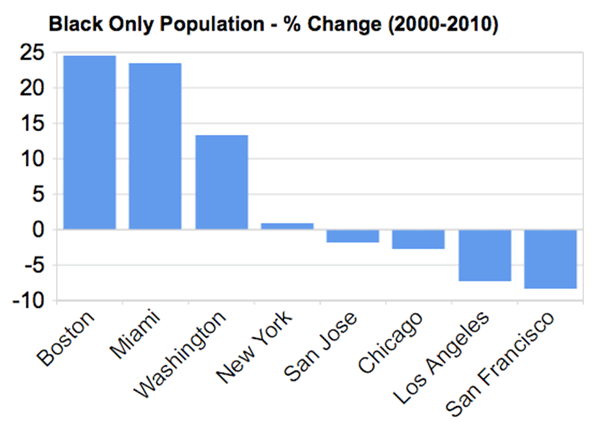

Here’s a more detailed look at the percentage growth in Black Only population in some tier one global type metros:

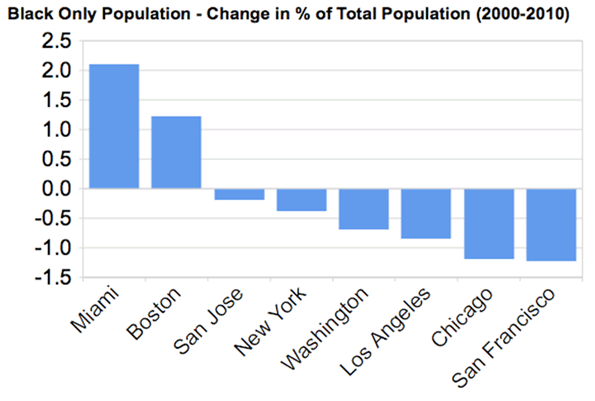

New York barely broke even on black population, while Chicago, LA, and the Bay Area all actually lost black residents, a stunning reversal from their past as black magnets. However, Boston, not a traditional black population hub, grew its black population strongly on a percentage basis, as did Miami and DC, though as noted before, the share change in DC was negative. Here is that metric for the same metros:

With the notable exceptions of Boston and Miami – and Philadelphia, seldom ranked highly as a global city but still a traditional large northern metropolis – most global city regions appear to be increasingly inhospitable to Blacks. Thus their model of success, whatever its appeal to some, at a basic level simply lacks inclusiveness. This shows its clear limits as an overall model for America’s urban centers as a whole.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile. Data analysis, maps, and charts in this piece were prepared with Telestrian.