Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman tells us that “sprawl killed Detroit” in his The New York Times column.

The evidence is characterized as “job sprawl” – that a smaller share of metropolitan area jobs are located within 10 miles of downtown Detroit than in the same radius from downtown Pittsburgh (see Note on Decentralization and “Job Sprawl”). It is suggested that this kept the city of Pittsburgh out of bankruptcy.

Not so. The subject is not urban form; it is rather financial management that was not up to par. State intervention may have been the only thing that saved the city of Pittsburgh from sharing Detroit’s fate.

Detroit and Pittsburgh: Birds of a Financial Feather

The city of Pittsburgh had been teetering on bankruptcy for some time. In 2004, the city’s financial affairs were placed under Act 47 administration (the Financially Distressed Municipalities Act“) by the state of Pennsylvania. One of Act 47’s purposes is to assist municipalities in avoiding bankruptcy. A 2004 state ordered recovery plan summarized the situation:

The City of Pittsburgh, already in fiscal distress, now stands on the precipice of full-blown crisis. In August 2003, the City laid off 446 employees, including nearly 100 police officers. City recreation centers and public swimming pools were closed, and services from police mounted patrol to salt boxes were eliminated. In October and November 2003, the City’s credit ratings were downgraded repeatedly, leaving Pittsburgh as the nation’s only major city to hold below-investment-grade “junk bond” ratings. With the City’s most recent independent audit questioning the City’s ability to continue as a going concern, a looming cash shortfall now threatens pension payments and payroll later this year. (emphasis added)

The good news is that Act 47 has worked so well that the city could soon be released from state control. It may have helped that all of this was overseen by former Democratic Governor Ed Rendell, whose tough administration saved another abysmally-managed municipality when he was mayor of Philadelphia more than a decade before.

Not everyone, however, is willing to grant that Pittsburgh has solved all its problems. Democratic candidate for mayor of Pittsburgh, Bill Peduto, recently urged Harrisburg to not release the city from Act 47 control. According to Peduto, “the city is not out of the financial woods,” and “we’re still in the middle of it, and in fact we have an opportunity in the next five years to build a sustainable budget for at least a decade.” Given the strong Democratic majority in the city, Peduto will probably be the next mayor.

The Key: Strong Management

In Detroit’s case, the state dithered for years, jumping in only when it was too late. Maybe the “tough love” of a Michigan-style Act 47 could have saved Detroit.

Meanwhile, best of luck to the Detroit bankruptcy court and Pittsburgh’s next mayor. Both were dealt a bad hand by predecessors who said yes to spending interests too often, to the detriment of residents and taxpayers.

——–

Note on Decentralization and “Job Sprawl”

The dispersed American metropolitan area has performed better than its mono-centric (downtown oriented) urban form of the past. American metropolitan areas are the most affluent in the world, and they are also the most decentralized. Decentralization of employment facilitates mobility, as economists Peter Gordon and Harry W. Richardson found 15 years ago. Work trip travel times are shorter and traffic congestion is less intense in US metropolitan areas than in similar sized metropolitan areas in Western Europe, Japan, Canada and Australia. At the same time, metropolitan areas around the world are themselves becoming more decentralized. The bottom line is that better mobility facilitates greater economic growth, which also reduces poverty.

Comparing the “job sprawl” of Detroit and Pittsburgh not only misses the point; it also glosses over differences that render any comparison virtually meaningless.

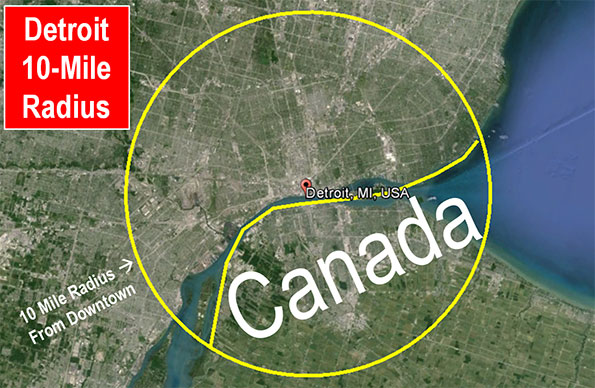

Detroit is Larger: The Detroit metropolitan area has nearly 60 percent more jobs than the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. Other things being equal, this would mean that Detroit would cover more area than Pittsburgh. As a result, even if the employment densities were equal, a smaller percentage of the jobs would be within 10 miles of downtown Detroit and within 10 miles of downtown Pittsburgh.

Nearly Half of Detroit’s 10 Mile Radius is in Canada and a Lake:But other things are not equal. Approximately 40 percent of the area within 10 miles of downtown Detroit is in Canada or in Lake St. Clair. Canadian jobs are appropriately excluded from the Detroit “job sprawl” numbers developed by the Brookings Institution (Figure), and no 10 mile radius comparison can thus be made to Pittsburgh. None of the 10 mile radius from downtown Pittsburgh is in Canada and none of it is in a large lake.

See Also: Peter Gordon’s Blog: Detroit

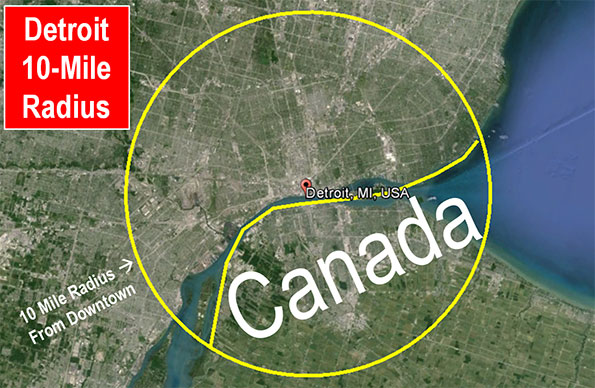

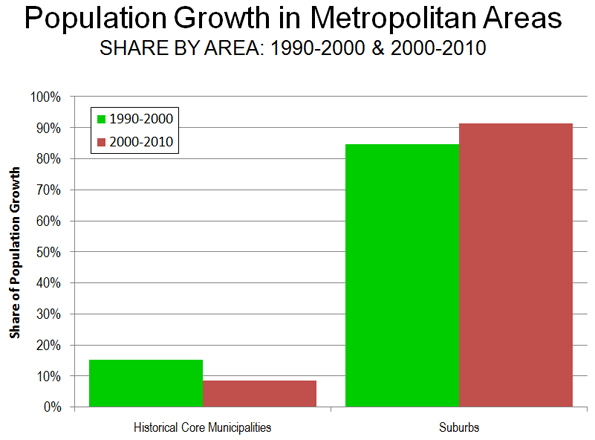

Combined, the fastest growing suburbs and exurbs with more than 25,000 population grew more than 3.5 million, while the municipalities outside the major metropolitan areas grew 1.5 million, for a combined growth of more than 5.0 million. The smaller high growth municipalities (under 25,000), nearly 1,200 of them, both major metropolitan and outside, grew another 2.5 million.

Combined, the fastest growing suburbs and exurbs with more than 25,000 population grew more than 3.5 million, while the municipalities outside the major metropolitan areas grew 1.5 million, for a combined growth of more than 5.0 million. The smaller high growth municipalities (under 25,000), nearly 1,200 of them, both major metropolitan and outside, grew another 2.5 million.