Scarcity leads to creativity out of necessity. That’s the pop culture meme at least. Think “starving artist,” or the survivors in Survivor. The thinking has penetrated the business culture as well. For example, in the shadow of the 2008 recession, Google founder Sergey Brin, in a letter to his shareholders, writes: “I am optimistic about the future, because I believe scarcity breeds clarity: it focuses minds, forcing people to think creatively and rise to the challenge.”

But a recent book, Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, by Ivy League psychologists Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir, states otherwise. Through years of investigative research, the authors found that people operating from a bandwidth of scarcity don’t have the luxury of preemptive thought. Rather, being in survivor mode saps a person’s cognitive reserve.

“Think about being hungry,” says Shafir in a piece in Pacific Standard. “If you’re hungry, that’s what you think about. You don’t have to strain for years—the minute you’re hungry, that’s where your mind goes.” The mental preoccupation extends to unpaid utility bills, debt, or, more generally, anything that’s life-pressing, he adds. The effect drains resources from a person’s “proactive memory”.

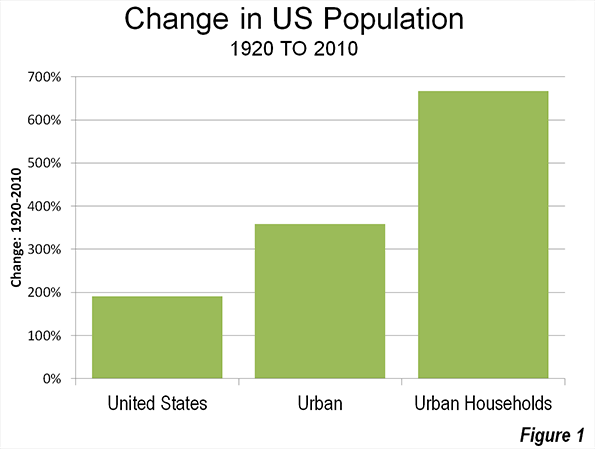

Think of the absence of scarcity, then, as the freedom to think, visualize, and create. The results of Mullainathan and Shafir’s findings have implications for cities. Specifically, it’s widely theorized that cities must innovate to survive, and it is a city’s creative reservoir—which is dependent on the size of its educated workforce—that will nurture innovation. This is how a city of soot can evolve into a city of software, not unlike what has occurred in Pittsburgh.

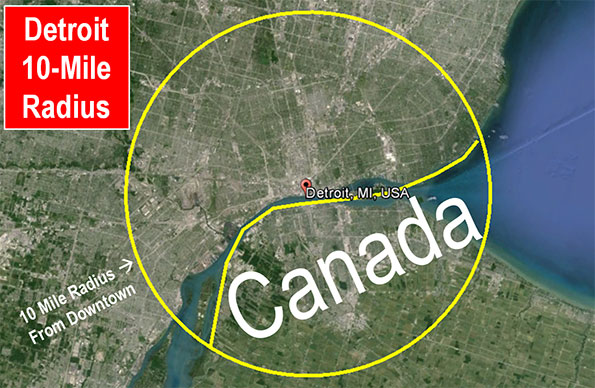

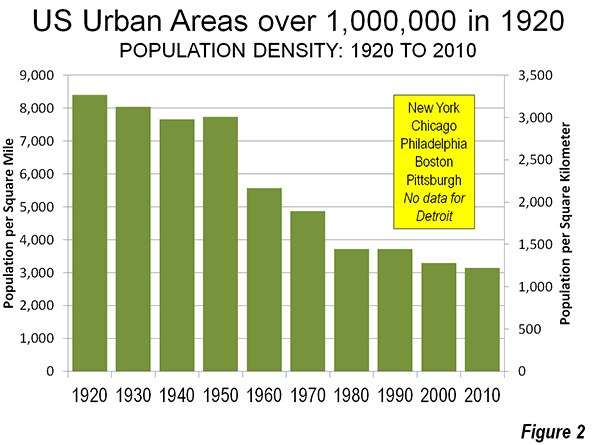

But what about Rust Belt cities struggling with high rates of poverty? Over 36 percent of Detroit’s 700,000 plus are below the poverty line. In Cleveland, the poverty rate is 33 percent of nearly 400,000. The national poverty rate is 14 percent. This is a ridiculous amount of brain capacity consumed by unforgiving reality. No wonder Detroit inches to get a leg up. The feral dogs, abandoned houses, and creditors looking for money have eaten up the capability to envision. Hence, the collective exasperation, and the bankruptcy death spiral.

What will save the Clevelands and Detroits? The most prescribed cure is to find a way to attract more educated people. This has led cities across the country to compete for the vaunted “creative class” professional demographic. To urban theorist Richard Florida, to get creative types a city must have “[an] indigenous street-level culture – a teeming blend of cafes, sidewalk musicians, and small galleries and bistros, where it is hard to draw the line between participant and observer or between creativity and its creators.”

According to Florida, a city needs to know it is on stage,and compete for the attention of a select demographic. In theatre parlance, this is called “capturing the audience experience.” In urban place-making parlance it is called “principles of persuasion” that emphasize novelty, contrast, surprise, color, etc.

In other words, cities must become the collective embodiment of Robin Williams.

Then, once you get your audience, you just watch them go, says Florida, as creativity is “a social process.” Creativity is bred by “the presence of other creative people.” The scarcity of creativity in a poor city hypothetically gets filled up by the big-bang spontaneity of two creative types talking, neurologically egged on, no doubt, by a festival performer on stilts in a clown suit sauntering before them.

If this strategy sounds like an overly simplified way to change what ails Detroit and Cleveland, it’s because it is. In fact Florida himself acknowledged this, stating in Atlantic Cities that, “On close inspection, talent clustering provides little in the way of trickle-down benefits [to the poor].” In fact, because housing costs rise, it makes the lives of lower- and middle-income people worse.

But cities keep revitalizing this way because it is a feel-good prescription that is politically palatable. Who hates art, carnivals, drinking, and eating? Displays of abundance provide the incentive to look the other way. Writes Thomas Sewell, “The first lesson of economics is scarcity: There is never enough of anything to satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics”.

Where does that leave the millions operating on the wrong side of scarcity? Florida’s answer is for cities to somehow convince corporate America to pay their service workers more. While admirable, I doubt Daniel Schwartz, CEO of Burger King, is listening.

Another option would be refocusing the lens through which modern urban revitalization is viewed. The default setting is to compete for scarcity of the educated elite. Instead, we should alleviate the scarcity from the struggling. But flipping this script requires cities to give up on the idea that there is some audience that will save them. It is a city’s people who ultimately ruin or save themselves.

In the meantime, the urban play continues. Cleveland is directing $4 million dollars of its casino windfall profits into the creation of an outdoor chandelier that will hang at an intersection outside of Playhouse Square, the city’s theater district. The design, evoked by chandeliers inside the Playhouse itself, is intended to blur the line between drama and reality, and will “add glittery outdoor glamour to a district that tends at times to look gray and lifeless,” according to architecture critic Steven Litt–all the while making the intersection “feel like a giant theater lobby”.

But the script on Cleveland’s streets is one of hardship, not glittery glamour. Here’s hoping the outdoor chandelier illuminates that scarcity to those walking beneath it.

This piece was originally published in Belt Magazine.

Richey Piiparinen is a writer and policy researcher based in Cleveland. He is co-editor of Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology. Read more from him at his blog and at Rust Belt Chic.

Lead photo by David Shvartsman.