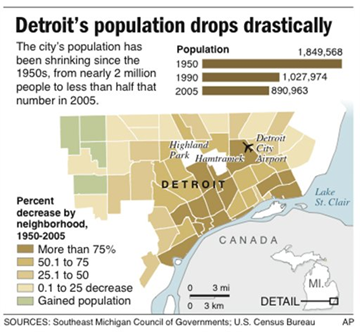

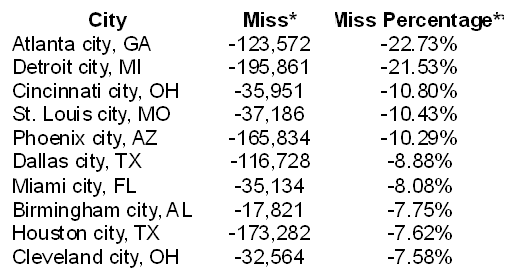

Detroit, not only in the US but across the globe, has become the poster child for urban decay. The city lost 25% of its population between 2000-2010, and over half its population since 1950. Over 90,000 houses stand empty, and many neighborhoods have been completely abandoned.

The burden of maintaining infrastructure and law enforcement in a city with an eroding tax base and sparse population has lead to attempts to “shrink” the city. This means bulldozing several areas of the city, and relocating existing residents. Current Mayor Dave Bing realizes this, and has pledged to knock down a staggering 10,000 structures during his first term. In the past such slum clearances lead to vigorous opposition from urbanists like Jane Jacobs, who argued that top down approaches to urban redevelopment would cause a great deal of pain, for little to no benefit. Yet despite the fact that Jacobs is widely admired by planners, the plan to shrink the city has met with little opposition in Detroit. Frankly, unless Detroit sees a major population surge, shrinking the city may sadly be necessary.

Last week, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg appeared on NBC’s Meet the Press, and at one point mused about using immigration policy to repopulate the city. Bloomberg didn’t offer a substantive policy proposal, but the premise makes perfect sense. Most of Detroit’s problems stem from the fact that fewer and fewer people are working and paying taxes in the city. There is more infrastructure than people need or the city can afford.

Ultimately the issue then is getting people to live in Detroit. But the biggest problem, even with a mild resurgence in the auto sector, is that Americans, and even most Michiganders, don’t want to live in Detroit, even with jobs.

But for many immigrants, Detroit would seem like a major upgrade over their current living situation. This is not as far-fetched a notion as some may believe. Here’s a proposal for Detroit based on an unlikely Canadian immigration success story: Winnipeg.

Learning from Winnipeg

When Americans think of Winnipeg, they think of white guys wearing earmuffs in July, speaking with the kind of Canadian accents typically ridiculed on American sitcoms. When Canadians from outside of Manitoba think of Winnipeg, they think of a former industrial city that is hardly a draw to the much sought after “creative class” even though the city has the nation’s lowest housing cost. What no one from outside the city associates with Winnipeg is immigration.

Winnipeg’s immigration success is not well known outside of the province, but it is hard to dispute the facts. Smart immigration policies have helped Winnipeg stabilize its population and reverse the city’s decline.

Between 1971-1996, the city of Winnipeg grew by just under 16%, or roughly 0.6% per year. Like many North American cities, all of the growth was taking place in the suburbs. In fact, the population of Downtown Winnipeg shrunk by 23.25% during that period. Though the rate of decline is nowhere near that of Detroit, the causes and effects are similar. Manufacturing declined; people moved to the suburbs, aided by highway expansions and low cost automobiles; residents moved to more entrepreneurial cities, such as Calgary; ensuing job and population decline lead to a decline in safety. The most notable difference is that racial tensions in Detroit exacerbated suburban flight. But the similarities are sufficient to use Winnipeg as a model.

Using immigration to reverse population decline in Manitoba

In 1998, the Province of Manitoba introduced the Provincial Nominee Program, which gave the province the ability to recruit immigrants over and above federal immigration quotas. Since Manitoba was not seen as the most attractive place for new immigrants to settle, only 1.8% of immigrants to Canada settled in the province between 1996-2000 (Note 1). Since the introduction of the nominee program, immigration to the province has increased by 250%. The increase in the City of Winnipeg has been staggering. In the years 1996-2000, the city saw 15,809 new immigrants. In just one year, 2007-2008, the city attracted 16,585 immigrants. Equally as important, 78% of Manitoba immigrants stay in the province, which is a significant improvement over the 1980s, when they had a retention rate of less than 50%. Increased immigration ended Manitoba’s population stagnation, and the province now enjoys consistently positive net migration.

Economic outcomes of Manitoba immigrants

A survey of immigrants who migrated to Manitoba through the provincial nominee program shows promising results. Three quarters of participants surveyed have never experienced involuntary unemployment. Of those surveyed, 85% were employed, and 7% were in school. While the average annual household income of $49,066 for participants is lower than the provincial average of $60,242, they are generally making enough money to live reasonably well, contributing to the provincial and municipal tax bases.

Reasons for the program’s success

Of course, mass immigration often creates challenges for recipient regions. Aside from the need for immigrants to find jobs, they also often require language training, and educational upgrading to meet certification levels for their professions. However, the success of the program shows that participants were by and large able to overcome these difficulties. Some of this can likely be attributed to the fact that immigrants of similar backgrounds tended to cluster together, some integrating into communities with existing settlers of similar backgrounds. The primary examples of these two patterns are the concentration of Filipino immigrants in Winnipeg, and the large number of Mennonites from Germany, Mexico, and South America who integrated into existing Mennonite communities. This can be important, since it allows for them to develop, or take advantage of informal support networks. Living in a community with speakers of the same language makes it easier for immigrants whose first language is not English to integrate into the community, and can help with finding employment.

Benefits of targeted immigration to Detroit

Immigration is often a source of innovation and entrepreneurship. Recent studies have shown that immigrant entrepreneurs in America have created more jobs for existing Americans than for other immigrants. More people moving to Detroit would also mean more customers for the service industry in the city. And by paying property taxes, they would help to keep the city government afloat. Perhaps the most important benefit would be that more people generally would make the city safer. Criminals, after all, hate witnesses.

Hopeful signs from recent immigration to Detroit

Recently, Detroit has experienced an influx of Latino and Muslim immigration. Despite the stigma attached to these groups by many Americans, anecdotal evidence suggests that these newcomers have been a boon to the city. According to the Immigration Policy Center, Arab American employment now contributes $7.7 billion to the Detroit metro economy, and provides $544 million in tax revenue to the state. They now support over 140,000 jobs in the city. Latino immigrants are being credited with helping to revitalize Southwest Detroit, which saw $200 million of investments between 1993-2008, and the area’s population grew by nearly 7% between 1990-2000 even as most of the city declined. The City is now home to nearly 50,000 Latinos, up from under 20,000 in 1990.

And for those who claim immigrants take American jobs, the evidence suggests the opposite. Despite the fact that immigrants have lower average wages than non-immigrants, they manage to have a disproportionate economic impact in many cities, Detroit being one of the best examples. According to the Fiscal Policy Institute, immigrants contribute 1.3 times as much to the economy per capita as non-immigrants in Detroit. This means, among other things, they disproportionately create jobs and contribute to the tax base.

Policy recommendations

Creating a targeted immigration program would require co-operation between municipal, state and federal governments. The policies recommended here are one set of options among many.

- The federal government should create an ”urban revitalization” visa category to allow for municipalities with severe demographic declines to accept immigrants without counting them towards immigration quotas.

- The state of Michigan, or other similarly challenged states, should create a specific program modeled on Manitoba’s provincial nominee program.

- Immigrants should be required to prove that they have the financial means to support themselves for a specified amount of time in the absence of income. This would ensure that they didn’t burden the existing welfare system.

- Participants in the program could be required to undertake language training at their own expense, or to prove a basic competence in English.

- The City of Detroit should move more aggressively towards allocating abandoned buildings to provide housing or places for businesses of immigrants, or anyone else who wants to occupy them for that matter. Filling buildings means more property taxes.

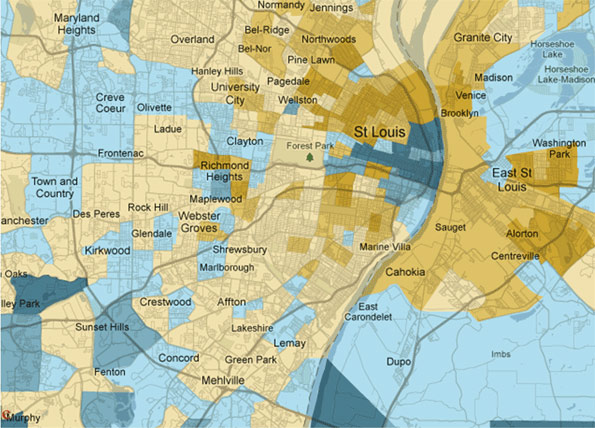

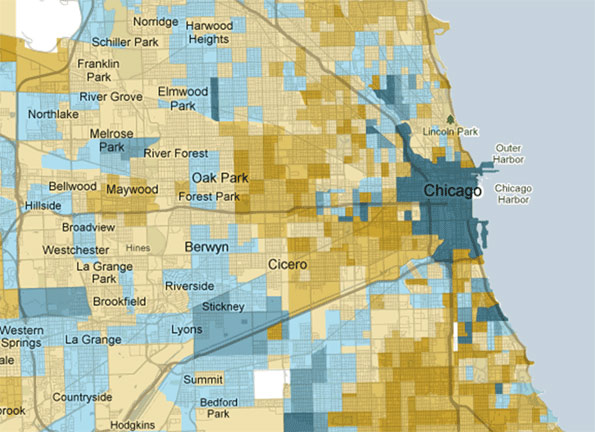

- The City should concentrate on settling new immigrants of similar ethno-linguistic backgrounds into specific underpopulated areas. Rather than simply allowing a certain number of immigrants into the city, they could create zones with high vacancy levels, and allow immigrants who apply to the program to move into these zones initially. The aim should be to populate one neighborhood every two years to fill current vacancies.

- Instead of punitive measures to force immigrants to stay in Detroit, the city should provide incentives to stay. This could include requiring immigrants under this program to sign long term leases with large deposits, or to purchase property. This is preferable to attempting to monitor the movement of immigrants.

- The city and state should attempt to partner with businesses, who may be interested in opening operations in the city due to the influx of immigrant labor. This could help to give further incentives for new immigrants to stay, and create jobs for existing unemployed residents.

Many of these recommendations require more micromanagement than I’d personally prefer, but address political and economic realities. Simply allowing anyone and everyone to immigrate to Detroit or anywhere else in America is a political non-starter. Also, the dire budgetary situation facing the City of Detroit and the state of Michigan means that neither can afford to allow new immigrants to become economic liabilities. After all, the justification for this program is to replace the tax base and reduce crime, not to create a new underclass. Though there would certainly be some hiccups, evidence in Winnipeg and Manitoba could help to revitalize both Detroit and much of the state of Michigan. Failure to undertake an aggressive revitalization strategy will make an aggressive shrinking strategy inevitable. Given the two choices, revitalization seems vastly preferable.

—

Note 1: Unless otherwise noted, data on the Manitoba Provincial Nominees Program is based on http://www2.immigratemanitoba.com/asset_library/en/resources/pdf/pnp-manitoba-provincial-nominee-program-tom-carter-report-2009.pdf

Steve Lafleur is a public policy analyst and political consultant based out of Calgary, Alberta. For more detail, see his blog.

Photo by Arlo Bates

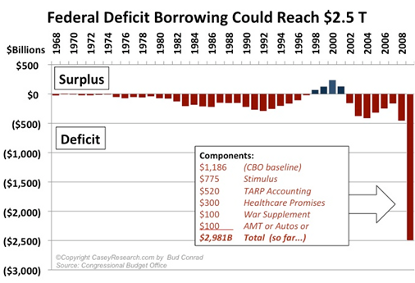

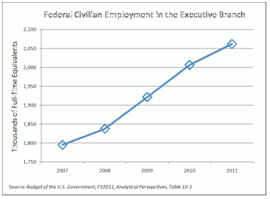

The second leg of Obama’s troika was new government employment. He was successful in signing his health care reform into law but delayed implementation to 2014. The 2010 election that changed 63 House seats to the Republicans, has acted to unwind much of this legislation. If not repealed outright, Obamacare will likely face starvation from Republican cuts in funding necessary to implement the 2,900 page law with its hundreds of new federal regulations. Federal civilian employment in the president’s 2012 budget, will be 15 percent higher in 2011 than it was in 2007. This effort is also likely to be stymied.

The second leg of Obama’s troika was new government employment. He was successful in signing his health care reform into law but delayed implementation to 2014. The 2010 election that changed 63 House seats to the Republicans, has acted to unwind much of this legislation. If not repealed outright, Obamacare will likely face starvation from Republican cuts in funding necessary to implement the 2,900 page law with its hundreds of new federal regulations. Federal civilian employment in the president’s 2012 budget, will be 15 percent higher in 2011 than it was in 2007. This effort is also likely to be stymied.