What if we achieved the urbanist dream, with people deciding en masse to move back to the city? Well, that would create a big problem, since there would be no place to put them. Many cities hit their peak population in 1950, when the US total was 150 million. Today it is over 300 million, with virtually all the growth taking place in the suburbs.

So where would these new urbanites reside? With the enormous losses in our urban housing stock, our cities lack the residences to hold even their 1950 population. A recent survey found that one third of all the lots in Detroit are now vacant, for example. And even if all the old housing was rebuilt, declines in household sizes, particularly in urban areas, has reduced the effective carrying capacity of the old urban fabric even at historic densities.

But there’s an even bigger challenge to wholesale urbanization from future population growth. The Census Bureau estimates that the US will add nearly 100 million more new people by 2050. If you look at the few cities in the country that have large inhabited urban cores, they hold a relatively small percentage of the current population. New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston, Seattle and Washington, DC combined barely hold 20 million people. Even if all these cities doubled in population by 2050, they would only be able to hold 20% of the net new growth expected over the next four decades.

And achieving even that level of urban growth is simply not realistic. Most of the existing highly urbanized cities are already largely full of buildings. Even where land is available, zoning restricts what can be built there, and increasing densities is politically difficult. New York City has been the most aggressive on the growth front, rezoning 20% of the city under the Bloomberg administration, although many sections have actually been downzoned.

But even this effort could accommodate a projected one million new residents by 2030. Chicago is going the other direction. When it introduced new zoning under the Daley administration, permitted densities were actually reduced in most cases, though Chicago remains perhaps the only truly urban city with large amount of vacant or underutilized land for redevelopment. Ed Glaeser calls for building skyscrapers in California, but San Francisco residents are imbued with a strong anti-development mindset and have long railed against the “Manhattanization” of their city.

America could not be reshaped from a primarily suburban to a city-centric country without a massive shift in local political mind-sets. Rather than attempting that exercise in futility, urban advocates should adopt much more modest goals that, although limited, could be completely transformational for our cities.

There’s been much made of the return to the city. Indeed, large tracts of the urban cores of many places have been utterly remade. But most of the cities where this has happened have been America’s largest tier one cities – New York, Chicago, Boston, etc. They have achieved the point of self-sustaining urban growth, and are well positioned to attract more residents, particularly the upscale and childless, young singles and students and recent immigrants.

In contrast, smaller cities have seen a few hundred downtown condos and such, but not a real urban renaissance. There is still a lot of work to do in those places.

The way to do this is to adopt the “10 percent solution”. That is, for most cities, they should develop a strategy that tries to capture somewhere between 5 and 15 percent of the net new growth in their metro areas. If a city can get more, great. But for any growing region, even 10 percent would create a dynamic of massive change in the urban core.

Consider Indianapolis, a region with healthy regional growth that is above average but not among the nation’s leaders. The Indianapolis metro area is adding people at a rate of about 200,000 people per decade. Center Township, which is the urban core of the city, peaked in population in 1950 at 337,000 people. Today it is at 167,000, a decline of 50%, on par with America’s greatest urban collapses

But what if the urban core managed to capture 10% of that new growth? That’s 20,000 new residents, very easy to physically accommodate within a decade. What would 20,000 new residents do to central Indianapolis? What would it do to the entire dynamic of the city? It could be completely transformational.

Such a modest capture of new population would catapult central Indianapolis into one of the absolute top growth areas in the region. Only one suburb is on track to add that many or more people during the 2000s. Many other suburbs are considered prosperous and fast growing despite adding only a few thousand people. Even that limited influx creates a pattern of growth vs. stagnation and decline. That’s where urban Indianapolis needs to get.

One of the great advantages of targeting 10% market share in new growth is that it frees the city to pursue a market segmentation strategy. It doesn’t have to try to convince vast numbers of suburbanites – the vast majority of whom are likely to stay in place – to make a radical lifestyle change. Rather, the core can market to specific segments that it is best positioned to attract, and put together the most compelling and differentiated product to attract them.

One potential market is those who want an urban environment but can’t afford to live in one of the expensive tier one cities. They could market themselves to people who find themselves priced out of the biggest cities, but would settle in a smaller, but still vibrant urban environment.

Can Indianapolis do it? As with many cities, there is already some evidence that it could. In the 2000s, decades of population decline came to an end in 2006, and Center Township started adding an estimated 400 people per year. The jury is still out on whether the estimates are confirmed by the census count and whether it can be sustained, but it still amounts to 4,000 people per decade, showing that the city is already starting to make progress.

Cincinnati provides another example. It is a metro growing a bit less than the national average, but still adding people at a rate of about 150,000 per decade. The city of Cincinnati declined from a peak of 503,998 in 1950 to 333,336 today, a loss of 170,000 people. Again, if the city captured 100% of just regional growth, in little more than a decade it would be back to a record high population. That’s not realistic of course, but 10% of that total, or 15,000 people, would still make a tremendous impact on the city. Like Indianapolis, there’s already some sign of an inflection point, as the city population began growing again in the 2000s.

Can this 10% solution really happen? The answer is a resounding Yes, because it is already happening in Atlanta. Its reputation as a sprawlburg overshadows the fact that it is experiencing one of America’s most impressive urban core booms. The city of Atlanta has added almost 120,000 new residents since 2000, an increase of 28%. This is a mere 10.5% of the metro area’s growth during that time – but it has totally changed the city. Atlanta lost over 100,000 people from its 1970 peak, but is now at an all time high.

Viewed in this realistic light, there is huge reason for optimism about rebuilding the urban cores of even our Rust Belt cities. Frankly, with the required market share of growth to get there so low, there’s no excuse for not making it happen. If city leaders can’t figure out how to attract even 10% of the market, they deserve to lose. If they can do better, great. And once they’ve captured that 10% base, and restarted a growth pattern, they can figure out how to get more ambitious and expand market share.

For regions with population decline, like Detroit and Cleveland, there’s a different and much more challenging dynamic. But for cities with even modest regional population growth, there’s all the opportunity in the world to attract new urban residents and completely change the game for their urban cores.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.

Photo: Carl Van Rooy (vanrooy_13)

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain.

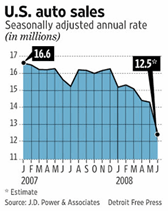

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain. Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.

Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.  The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.

The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.