Analysts occasionally note that urban areas ("cities") are becoming larger and denser. This is only half right. It is true that most of the world’s urban areas are becoming larger, with megacities like Delhi, Jakarta, Shanghai, Beijing and Manila adding more than five million people in the last decade and most other urban areas are growing, but not as fast.

Understanding Urban Areas: However almost without exception, urban areas are getting less dense. Because there is so much confusion about city "definitions," a clarification is required. The only geography for which overall urban density can be measured is the urban area, which is the area of continuous development. The urban area is not constrained by municipal or other jurisdictional boundaries and does not include rural (undeveloped) territory, even if it is in a "central city" (such as Rome, Ho Chi Minh or Marseille, with their expansive boundaries). An urban area is also different from a metropolitan area, because metropolitan areas (as labor markets) always include rural territory, which is by definition not urban.

1960-1990 Data: Historical urban population density is not readily available. Kenworthy and Laube were pioneers in this area, publishing estimates from 1960 to 1990 for a number of urban areas. That data indicates density losses in the more than urban areas for which they were able to develop comparable data. The world average decline was 20 percent, ranging from 15 percent in the United States to 29 percent in Europe and 33 percent in Australia. While Tokyo was doubling in population, its population density was dropping 17 percent between 1960 and 1990. While Zurich was adding 21 percent to its population, it was becoming 13 percent less dense.

Recent Data: The dispersion continues, which is indicated by these high-income world cases:

Today, the ville de Paris has 700,000 fewer people than at its peak, and inner London (generally the former London County Council area) has lost more than 1,500,000 people since its peak. All growth has been in lower density suburban areas in both the London and Paris urban areas.

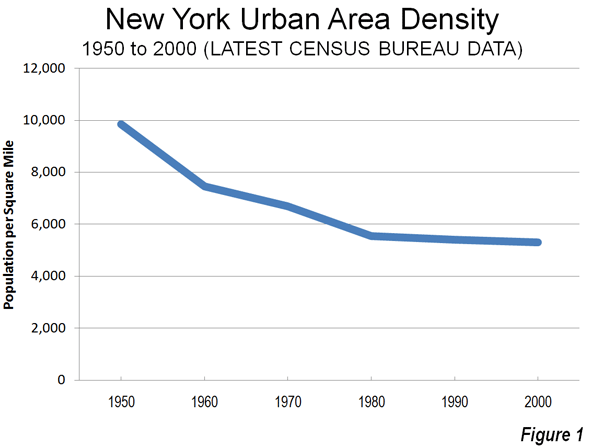

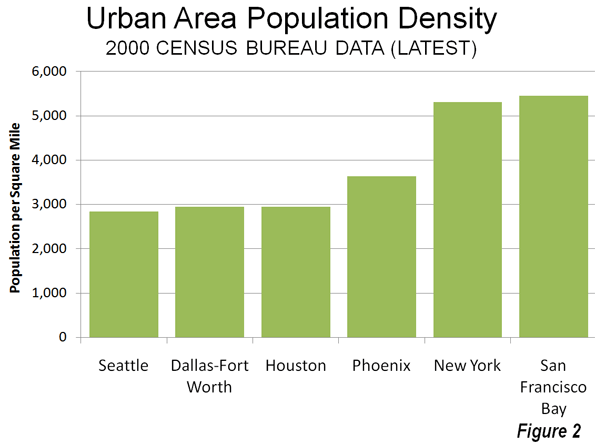

In the United States, urban areas with more than 1,000,000 population more than doubled in population from 1950 to 2000 (2010 data not yet available), while the population density dropped by nearly one-third. Detailed analysis indicates that this trend has continued over the past decade in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas-Fort Worth, Seattle, St. Louis and other major US urban areas.

The dense core city of Seoul has been losing population and all growth has been in the suburbs, which are lower density.

The dense urban core of Milan has experience substantial population losses, while the less dense suburbs have captured all the growth.

Dispersion is not limited to high income urban areas, with declining densities in evidence across lower and middle income nations as well. For example:

Nearly all of the growth in Jakarta has been in the suburbs for the last 20 years, while the core has gained little in population. The net effect is a less dense, but much larger urban area, because the suburbs are not as dense.

Nearly all of the growth for 30 years in Manila has been in the suburbs, while the core city. Again, the urban area has become much larger, but much less dense because the suburbs are much less dense.

The dense core of Shanghai has lost population and all growth has been in the suburbs, which are lower density.

The population in the dense core of Beijing has nearly stopped growing, with nearly all population in the suburbs, which are lower density.

The core of Mumbai has lost population in two of the last three census periods, while all growth has been in the suburbs, which are lower density.

The urban core of Mexico City has been declining in population since 1960 and all of the growth has been in the suburbs, which are less dense.

The dense core city of Buenos Aires has fewer people today than in 1947, while at least 8 million people have been added to nearly 1,000 square miles of lower density suburbs.

Urban growth continues to be overwhelmingly in less dense suburban areas, rather than in the more dense urban cores, and as a result even as urban areas grow, they become less dense. This is how cities grow.