The news is full of stories about the the impact of the ARRA on job creation, including this one from the The Wall Street Journal about a shoe store owner who created or saved nine jobs with less than $900.

In the story, the Army Corps of Engineers spent $889.60 buying boots from shoe store owner Buddy Moore of Kentucky. Because the boots were purchased with ARRA funds, the Corps asked Buddy to report how many jobs the boot order had “created or saved.” He and his daughter struggled with paperwork, online forms, and a “helpline,” only to make a wild guess 15 minutes before the reporting deadline that they had created nine jobs.

Though not completely spelled out in the article, the impression is that Buddy and his daughter reasoned that they had created or saved nine jobs, because their boots had “helped nine members of the Corps to work.”

This sort of misreporting is now fodder for ARRA opponents, and is the last thing that the White House wanted on its hands. In July the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued this memorandum and created a series of PowerPoints and PDFs intended to assist ARRA recipients with their reporting.

These documents do not appear to be currently available on the White House website, but you can find the Google doc here. This list (also not directly available) shows that the Army Corps of Engineers is and was considered a primary recipient. Given its status, it is the one required in the initial PowerPoint to report the “job creation narrative and number.”

As a prime recipient, the Corps should have been briefed on the fact that the key data issue to avoid was: “Significant Reporting Errors: (which are) instances where required data is not reported accurately and such erroneous reporting results in significant risk that the public will be misled or confused by the recipient report in question.”

They also would have had to listen in to this presentation on data quality, which stresses that prime recipients are fully responsible for the quality of the data. The Corps could have caught the reporting mistake by running a simple math equation, which would have indicated that the shoe store had created a full-time job for every $98.84.

If this were true, only $2 billion (administered by Buddy Moore) would have reemployed every single unemployed person in the US, a savings of $785 billion to the American taxpayer.

In the end, it turns out that because the payment made by the Corps was less than $25,000, the Corps (while responsible for reporting the total number and amount of small sub-awards less than $25,000) was not required to have Buddy Moore report anything.

Prime recipients are still responsible to report a total jobs creation estimate based off what sub-recipients and vendors do with the funds they disperse. To do that, the Corps could have called up Buddy and asked him to estimate the extra hours he worked for that specific order, and calculated Full Time Equivalents using those hour(s) by “… adding the total hours worked by all employees in the quarter, and dividing by the total hours in a full-time schedule.”

In this case, let’s assume he worked an extra hour filling the boot order. A quarter-year full-time job would take 520 hours to complete, so he would report that the Corps funds created 1/520 of a quarterly FTE (.001923 FTE), or just about 2/1000th’s of a full-time job for a quarter of the year. The shoe store’s estimate of job creation, therefore, was 4,680 times too big.

The OMB’s method of job reporting is, by our estimation, a good way of quantifying job creation. The problem, highlighted by the WSJ article, is that average businesses and recipients have had a hard time understanding what data was needed in the first place, and then what they were supposed to do with it.

Mark Beauchamp is a customer service representative at Economic Modeling Specialists Inc., an Idaho-based data and economic analysis firm.

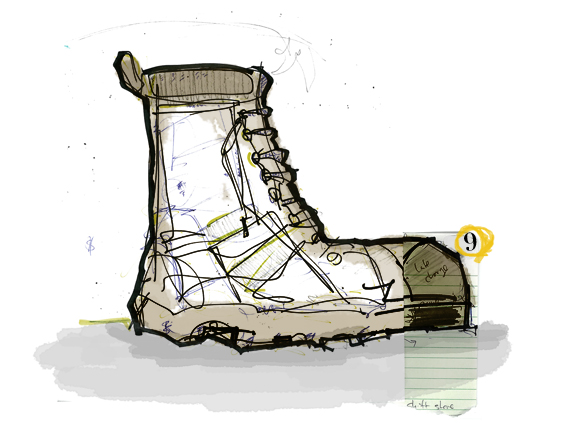

Illustration by Mark Beauchamp.