For the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, American liberals distinguished themselves from conservatives by what Lionel Trilling called “a spiritual orthodoxy of belief in progress.” Liberalism placed its hopes in human perfectibility. Regarding human nature as essentially both beneficent and malleable, liberals, like their socialist cousins, argued that with the aid of science and given the proper social and economic conditions, humanity could free itself from its cramped carapace of greed and distrust and enter a realm of true freedom and happiness. Conservatives, by contrast, clung to a tragic sense of man’s inherent limitations. While acknowledging the benefits of science, they argued that it could never fundamentally reform, let alone transcend, the human condition. Most problems don’t have a solution, the conservatives maintained; rather than attempting Promethean feats, man would do best to find a balanced place in the world.

In the late 1960s, liberals appeared to have the better of the argument. Something approaching the realm of freedom seemed to have arrived. American workers, white and black, achieved hitherto unimagined levels of prosperity. In the nineteenth century, only utopian socialists had imagined that ordinary workers could achieve a degree of leisure; in the 1930s, radicals had insisted that prosperity was unattainable under American capitalism; yet these seemingly unreachable goals were achieved in the two decades after World War II.

Why, then, did American liberalism, starting in the early 1970s, undergo a historic metanoia, dismissing the idea of progress just as progress was being won? Multiple political and economic forces paved liberalism’s path away from its mid-century optimism and toward an aristocratic outlook reminiscent of the Tory Radicalism of nineteenth-century Britain; but one of the most powerful was the rise of the modern environmental movement and its recurrent hysterias.

If one were to pick a point at which liberalism’s extraordinary reversal began, it might be the celebration of the first Earth Day, in April 1970. Some 20 million Americans at 2,000 college campuses and 10,000 elementary and secondary schools took part in what was the largest nationwide demonstration ever held in the United States. The event brought together disparate conservationist, antinuclear, and back-to-the-land groups into what became the church of environmentalism, complete with warnings of hellfire and damnation. Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, the founder of Earth Day, invoked “responsible scientists” to warn that “accelerating rates of air pollution could become so serious by the 1980s that many people may be forced on the worst days to wear breathing helmets to survive outdoors. It has also been predicted that in 20 years man will live in domed cities.”

Thanks in part to Earth Day’s minions, progress, as liberals had once understood the term, started to be reviled as reactionary. In its place, Nature was totemized as the basis of the authenticity that technology and affluence had bleached out of existence. It was only by rolling in the mud of primitive practices that modern man could remove the stain of sinful science and materialism. In the words of Joni Mitchell’s celebrated song “Woodstock”: “We are stardust / We are golden / And we got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

In his 1973 book The Death of Progress, Bernard James laid out an argument already popularized in such bestsellers as Charles Reich’s The Greening of America and William Irwin Thompson’s At the Edge of History. “Progress seems to have become a lethal idée fixe, irreversibly destroying the very planet it depends upon to survive,” wrote James. Like Reich, James criticized both the “George Babbitt” and “John Dewey” versions of “progress culture”—that is, visions of progress based on rising material attainment or on educational opportunities and upward mobility. “Progress ideology,” he insisted, “whether preached by New Deal Liberals, conservative Western industrialists or Soviet Zealots,” always led in the same direction: environmental apocalypse. Liberalism, which had once viewed men and women as capable of shaping their own destinies, now saw humanity in the grip of vast ecological forces that could be tamed only by extreme measures to reverse the damages that industrial capitalism had inflicted on Mother Earth. It had become progressive to reject progress.

Rejected as well was the science that led to progress. In 1970, the Franco-American environmentalist René Dubos described what was quickly becoming a liberal consensus: “Most would agree that science and technology are responsible for some of our worst nightmares and have made our societies so complex as to be almost unmanageable.” The same distrust of science was one reason that British author Francis Wheen can describe the 1970s as “the golden age of paranoia.” Where American consumers had once felt confidence in food and drug laws that protected them from dirt and germs, a series of food scares involving additives made many view science, not nature, as the real threat to public health. Similarly, the sensational impact of the feminist book Our Bodies, Ourselves—which depicted doctors as a danger to women’s well-being, while arguing, without qualifications, for natural childbirth—obscured the extraordinary safety gains that had made death during childbirth a rarity in developed nations.

Crankery, in short, became respectable. In 1972, Sir John Maddox, editor of the British journal Nature, noted that though it had once been usual to see maniacs wearing sandwich boards that proclaimed the imminent end of the Earth, they had been replaced by a growing number of frenzied activists and politicized scientists making precisely the same claim. In the years since then, liberalism has seen recurring waves of such end-of-days hysteria. These waves have shared not only a common pattern but often the same cast of characters. Strangely, the promised despoliations are most likely to be presented as imminent when Republicans are in the White House. In each case, liberals have argued that the threat of catastrophe can be averted only through drastic actions in which the ordinary political mechanisms of democracy are suspended and power is turned over to a body of experts and supermen.

Back in the early 1970s, it was overpopulation that was about to destroy the Earth. In his 1968 book The Population Bomb, Paul Ehrlich, who has been involved in all three waves, warned that “the battle to feed all of humanity is over” on our crowded planet. He predicted mass starvation and called for compulsory sterilization to curb population growth, even comparing unplanned births with cancer: “A cancer is an uncontrolled multiplication of cells; the population explosion is an uncontrolled multiplication of people.” An advocate of abortion on demand, Ehrlich wanted to ban photos of large, happy families from newspapers and magazines, and he called for new, heavy taxes on baby carriages and the like. He proposed a federal Department of Population and Environment that would regulate both procreation and the economy. But the population bomb, fear of which peaked during Richard Nixon’s presidency, never detonated. Population in much of the world actually declined in the 1970s, and the green revolution, based on biologically modified foods, produced a sharp increase in crop productivity.

In the 1980s, the prophets of doom found another theme: the imminent danger of nuclear winter, the potential end of life on Earth resulting from a Soviet-American nuclear war. Even a limited nuclear exchange, argued politicized scientists like Ehrlich and Carl Sagan, would release enough soot and dust into the atmosphere to block the sun’s warming rays, producing drastic drops in temperature. Skeptics, such as Russell Seitz, acknowledged that even with the new, smaller warheads, a nuclear exchange would have fearsome consequences, but argued effectively that the dangers were dramatically exaggerated. The nuke scare nevertheless received major backing from the liberal press. Nuclear-winter doomsayers placed their hopes, variously, in an unverifiable nuclear-weapons “freeze,” American unilateral disarmament, or assigning control of nuclear weapons to international bodies. Back in the real world, nuclear fears eventually faded with Ronald Reagan’s Cold War successes.

The third wave, which has been building for decades, is the campaign against global warming. The global-warming argument relied on the claim, effectively promoted by former vice president Al Gore, that the rapid growth of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was producing an unprecedented rise in temperatures. This rise was summarized in the now-notorious “hockey stick” graph, which supposedly showed that temperatures had been steady from roughly ad 1000 to 1900 but had sharply increased from 1900 on, thanks to industrialization. Brandishing the graph, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted that the first decade of the twenty-first century would be even warmer. As it turned out, temperatures were essentially flat, and the entire global-warming argument came under increasing scrutiny. Skeptics pointed out that temperatures had repeatedly risen and fallen since ad 1000, describing, for instance, a “little ice age” between 1500 and 1850. The global-warming panic cooled further after a series of e-mails from East Anglia University’s Climatic Research Unit, showing apparent collusion among scientists to exaggerate warming data and repress contradictory information, was leaked.

As with the previous waves, politicized science played on liberal fears of progress: for Gore and his allies at the UN, only a global command-and-control economy that kept growth in check could stave off imminent catastrophe. The anti-progress mind-set was by then familiar ground for liberals. Back in the 1970s, environmentalist E. J. Mishan had proposed dramatic solutions to the growth dilemma. He suggested banning all international air travel so that only those with the time and money could get to the choice spots—thus reintroducing, in effect, the class system. Should this prove too radical, Mishan proposed banning air travel “to a wide variety of mountain, lake and coastal resorts, and to a selection of some islands from the many scattered about the globe; and within such areas also to abolish all motorised traffic.” Echoing John Stuart Mill’s mid-nineteenth-century call for a “stationary state” without economic growth, Mishan argued that “regions may be set aside for the true nature lover who is willing to make his pilgrimage by boat and willing leisurely to explore islands, valleys, bays, woodlands, on foot or on horseback.”

As such proposals indicate, American liberalism has remarkably come to resemble nineteenth-century British Tory Radicalism, an aristocratic sensibility that combined strong support for centralized monarchical power with a paternalistic concern for the poor. Its enemies were the middle classes and the aesthetic ugliness it associated with an industrial economy powered by bourgeois energies. For instance, John Ruskin, a leading nineteenth-century Tory Radical and a proponent of handicrafts, declaimed against “ilth,” a negative version of wealth produced by manufacturing.

Like the Tory Radicals, today’s liberal gentry see the untamed middle classes as the true enemy. “Environmentalism offered the extraordinary opportunity to combine the qualities of virtue and selfishness,” wrote William Tucker in a groundbreaking 1977 Harper’s article on the opposition to construction of the Storm King power plant along New York’s Hudson River. Tucker described the extraordinary sight of a fleet of yachts—including one piloted by the old Stalinist singer Pete Seeger—sailing up and down the Hudson in protest. What Tucker tellingly described as the environmentalists’ “aristocratic” vision called for a stratified, terraced society in which the knowing ones would order society for the rest of us. Touring American campuses in the mid-1970s, Norman Macrae of The Economist was shocked “to hear so many supposedly left-wing young Americans who still thought they were expressing an entirely new and progressive philosophy as they mouthed the same prejudices as Trollope’s 19th century Tory squires: attacking any further expansion of industry and commerce as impossibly vulgar, because ecologically unfair to their pheasants and wild ducks.”

Neither the failure of the environmental apocalypse to arrive nor the steady improvement in environmental conditions over the last 40 years has dampened the ardor of those eager to make hair shirts for others to wear. The call for political coercion as a path back to Ruskin’s and Mishan’s small-is-beautiful world is still with us. Radical environmentalists’ Tory disdain for democracy and for the habits of their inferiors remains undiminished. True to its late-1960s origins, political environmentalism in America gravitates toward both bureaucrats and hippies: toward a global, big-brother government that will keep the middle classes in line and toward a back-to-the-earth, peasantlike localism, imposed on others but presenting no threat to the elites’ comfortable lives. How ironic that these gentry liberals—progressives against progress—turn out to resemble nothing so much as nineteenth-century conservatives.

This essay originally appeared in City Journal.

Fred Siegel is a contributing editor of City Journal, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, and a scholar in residence at St. Francis College in Brooklyn.

Photo: CarbonNYC

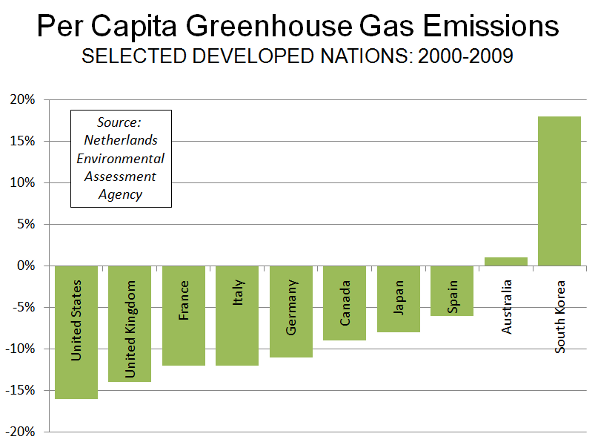

GHG emissions per capita increased in all of the developing nations surveyed except for the Ukraine (-12%) and Brazil (-1%). Such increases are not surprising, as people in developing nations move from the countryside to urban areas and as they seek greater affluence.

GHG emissions per capita increased in all of the developing nations surveyed except for the Ukraine (-12%) and Brazil (-1%). Such increases are not surprising, as people in developing nations move from the countryside to urban areas and as they seek greater affluence.