Economists and accountants could very likely have told us six months ago that Chrysler was doomed as a business and that the likely best course of action would be Chapter 11 bankruptcy and restructuring. Doing this in a timely manner would have saved the taxpayers billions of dollars.

But the politics were not right to permit this to happen at that time. So instead we invested billions of tax dollars to save it, only to find ourselves right back were we started. Except now the clock is striking twelve and it is the right time to reorganize the automaker – politically speaking.

The politics has worked to “force” Daimler, Cerberus, Banks, UAW and the U.S. taxpayer to forgive nearly $17 billion in debt, and to transfer ownership to a consortium that includes Fiat, U.A.W., and the U.S. and Canadian governments. The same fate may soon await General Motors given the current political atmosphere.

Government action is not driven so much by economics or accounting as it is by shifts and changes in public opinion and the political winds on Capitol Hill. Regardless of the problem and the consequences of delay, no issue will be dealt with until opinion has been properly shaped around it. This is inefficient by its nature, but government is not a business and cannot fail, so the consequences are never felt by government.

This means government will often invest in what’s next and ignore what is needed in the present. Why? Because the public likes the new and the novel and grows weary of the old and tried and true. Transportation infrastructure is a great example. It is an accepted fact that our road and bridge infrastructure is failing and will require billions of additional dollars to rebuild and reform into a 21st century, integrated mobility network. Yet there is no political will to address an issue which could seriously undermine our economic competitiveness costing us countless jobs and businesses.

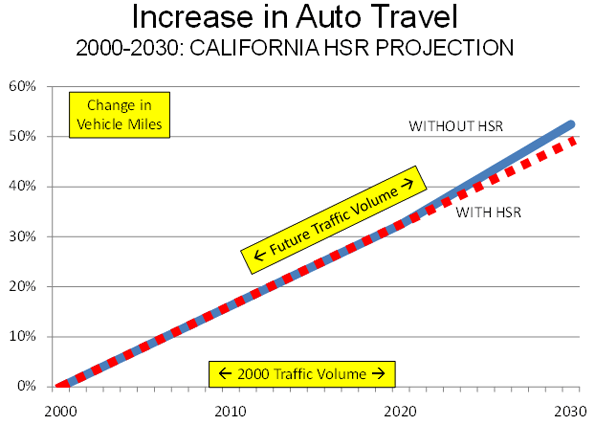

Politicians know that a solution will require new revenues and very likely a new user fee to augment the current gas tax. Raising taxes is not good for the long term political health of our elected “leaders” because the public does not want to pay for things. So rather than solve a pressing need, government proposes borrowing $8 billion to spend on high speed rail projects like the one to connect Disneyland and Las Vegas. This project works politically because it is filled with perceived benefits and no one really has to pay for them – we can pass it all on to the next generation.

As we move toward increasing the politicization of our economy where politicians replace CEOs, government becomes a major shareholder in corporations, and the metrics of elections replace standard accounting practices, we should remember the inherent and unintended consequences.

Businesses succeed or fail based on markets. The government’s attempt to create a false housing market with its affordable housing initiative is arguably one of the major contributing factors to our current recession. They will likely assert their new power in the automobile industry to create “green” cars that may or may not sell. What if consumers choose to buy Japanese, Korean or German label cars made in Mississippi or Alabama, instead of UAW-built cars from Michigan?

Markets work, and yet they are being ignored. The second most profound economic event of the past year (the collapse of the financial markets being the first) was when the price of gasoline moved above $4.00 a gallon in April of 2008. People drove less. Demand for SUVs plummeted. Ridership of public transportation increased dramatically. Many valued components of American way of life changed almost overnight.

What is often missed is the fact that government was powerless to do anything about gas prices. Elected leaders looked for scapegoats in speculators and commanded the heads of the Big Oil companies pay homage at their feet. They attacked profits, demanded more drilling, put their environmental agenda on the back burner. The crisis showed them to be feckless on the horns of a dilemma. When prices retreated swiftly in August 2008 and public opinion cooled on the issue, drilling for new energy disappeared from the radar and everything was “green” again. The problem has not disappeared of course, but only public support for a solution. Is this any way to run an economy?

Businesses concentrate on profit. Elected leaders focus on votes. Bad business decisions are unsustainable in a free market which metes out consequences with failure. Bad political decisions make an elected official unelectable, so it is always better to avoid conflict by putting off the really tough decisions for another day. This is not the way most Americans run their households, but it’s how politicians would run our economy – responding to opinion, not market conditions.

There are some very difficult decisions as we move through this economic downturn. Do we want more and more of the political processes to be incorporated into our economy on a permanent basis? Banks and financial institutions have already seen first hand the consequences of getting into bed with government. Our automobile industry is next in line. Let’s hope it is the end of the line, but it probably won’t be.

Dennis M. Powell is president and CEO of Massey Powell an issues management consulting company located in Plymouth Meeting, PA.