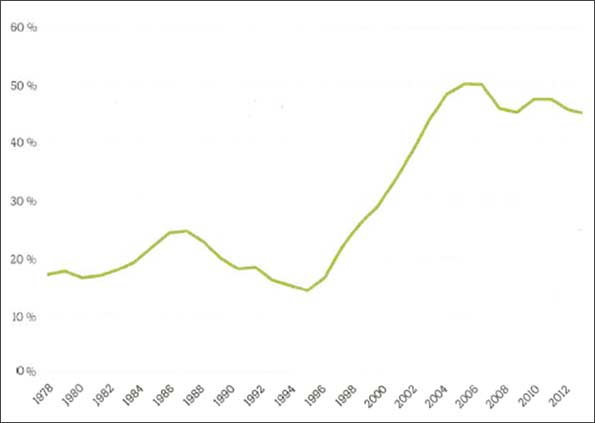

Press coverage of the recent European violence often draws a line from the Arab slums around Paris to the violence that has recently engulfed Brussels and Paris. According to this theory, Arab refugees from Morocco and Algeria, and, more recently, Syria, who have settled on the impoverished outskirts of Paris, are to blame for the terrorist attacks because France and Belgium have been reluctant to assimilate Arabs into their European cultures. And youth unemployment rates in the banlieues — suburbs — of Paris and Brussels are, indeed, more than fifty percent in some districts. Is it any wonder, the thinking goes, that disaffected Arabs have taken to fitting themselves with suicide vests, or spraying AK-47 bullets into crowded cafés?

Living on the Swiss border with France, and spending many days each year in France, I have long heard these urban-decay theories of political violence. I decided to investigate the link between unassimilated Arabs in the banlieues and the violence that has shaken Europe.

I made the trip in March with my bicycle, so that I could easily get around such notorious suburban ghettos as Clichy-sous-Bois and Le Blanc-Mesnil.

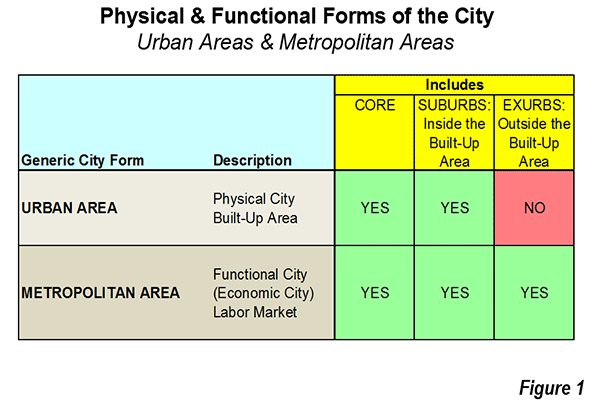

I couldn’t see every street or every crumbling apartment complex in the banlieues, obviously, but I did cover a wide swath of the Paris exurbs. And I tracked a course that, at least during the 2005 riots, would have followed the smoke of burning tires.

I include the above qualifier because many friends (most, I would say, have never explored the suburbs on a bike) don’t believe my conclusions, which are that the banlieues are not nearly as desperate on the ground as they are on television reports.

Especially after a terrorist incident, local media will invariably show pictures of dilapidated high-rise apartment buildings on the edges of Paris, and action shots of the police dragging suspected terrorists from these underworlds. The causes and effects would seem clear. But my observations led to conclusions that question that French connection.

Setting out from the Chelles train station, I had expected to come across 1970s-era South Bronx-like slums, only with an Arab motif. But as I rode through many Islamic neighborhoods, what surprised me is how different the banlieues are from the violent shadows on the evening news.

In those dispatches, the suburbs might well be an Arabic Calcutta.

Instead I found the these areas to be in the midst of urban renewal. Where ten years ago there were overturned cars and burning tires, I came across rows of working class houses (most well kept) and some new strip malls. On many corners there were the outlets of national franchises—as many McDonalds as mosques.

Clearly, France has spent millions in the banlieues; think of the construction that went on in American cities after the urban riots of the 1960s. The French government has replaced some of the post-war, high-rise towers of despair with smaller scale apartment buildings, what American city planners call “scatter-site housing.” Clearly, the sociologists have come to have more sway than the civil engineers.

Not every street I went down in places like Sevran or Aulnay-sous-Bois looked like a contemporary planner’s urban-renewal model. But more than I expected did.

So why has the violence moved from the halal shops in Clichy-sous-Bois to the Boulevard Voltaire in Paris?

Most articles about terrorist violence in France and Belgium make the point that Arab immigrants have yet to be integrated into local culture. Social isolation remains one of the possible causes of the new urban wars, and it is well documented in many descriptions of Arab culture in Europe.

Left out of these explanations for the Paris or Brussels violence is the extent to which an existing criminal underclass has committed itself to Islam, and not the other way around.

According to some candidates in the American presidential election, the European bombers and attackers are the kamikaze of a new religious order, taking their orders from the ISIS central command in Raqqa in the east Syrian desert.

It is true that many of the attackers have had the support of military planners, such as those from Saddam’s Baathist officer caste, who were ostracized when the US invaded Iraq.

But the aspect of the attackers that never gets on the evening news is the extent to which many of the bombers embraced Islam only after lives of petty crime, if not debauchery, in the same clubs they are now attacking.

The killers failed at school, in after-school programs, and at various low-level jobs, only to find the warm embrace of a prison imam speaking of injustices done to co-religionists on the Syrian frontier.

These rebels finally had a cause, however distant it was from their lives of street crimes. Their route to eternity, however, only passed through Raqqa by chance and convenience, not by providential design.

While I was in Paris, I made it a point to bicycle over to all of the sites that were attacked on November 13, and to the site of the earlier shootings at the magazine Charlie Hebdo.

I thought that by riding the stations of such a sad cross I might get some insight into what had motivated the killers.

The editorial offices of Charlie Hebdo have moved from the location of the attack. But on the side of the old building, a portrait of the slain editor, Stéphane Charbonnier, has been drawn. Of earlier threats he said: “I would rather die standing than live kneeling.”

The mournful side street near the center of the Paris gives no clue as to how the French rank the importance of press and religion in the hierarchy of its political freedoms. Would France feel the same about Charlie Hebdo if it had attacked Judaism as it did Islam?

Around the corner is the Bataclan nightclub, where almost 100 young French concertgoers were shot down in cold blood. Some flowers were propped against the closed doors. Otherwise, the pagoda-shaped building had the look of a failed theater, down and out in the latest economic depression.

Standing in front of the killing zone, I envisioned the Bataclan assassins less as holy warriors—jihadis on their way to martyrdom—and more as street thugs or contract hitmen.

Looking at the bullet holes in the plate glass windows of the nightclub, plus at some nearby cafés, I saw the gunmen as absent of any ideas or ideals. I thought more about Baby Face Nelson and the Dillinger gang (sometimes called the Terror Gang), with their running boards and machine guns, than I did about what candidate Ted Cruz calls “radical Islamic terrorism.”

I grant you that the killers were Muslim and that many had roots in the Paris suburbs, but I don’t think the poverty of the banlieues alone explains why anyone would attack a nightclub with automatic weapons, any more than crop failures in Sicily or Catholicism explain the violent rubouts committed by the mafia in the last 100 years.

Matthew Stevenson, a contributing editor of Harper’s Magazine, is the author, most recently, of Remembering the Twentieth Century Limited, a collection of historical travel essays, and Whistle-Stopping America. His next book is Reading the Rails. He lives in Switzerland.

Photo of the Bataclan nightclub in Paris by the author.