In the years after the Cold War, much was written about Europe’s emergence as the third great force in the global political economy, alongside Asia and the United States. Some, such as former French President Francois Mitterand’s eminence grise Jacques Attali, went even further: in his 1991 book Millenium Attali predicted that in the 21st century, “Japan and Europe may supplant the United States as the chief superpowers.”

This notion of a fading America has been embraced among some here as well, by authors such as Jeremy Rifkin who has written extensively about a “European dream” supplanting the American one on a global scale. In 2008, CNN anchor Fareed Zakaria predicted the rise of what he called “the post-American world,” with the U.S. still preeminent but losing ground, particularly to emerging countries in Asia. This view is widely held in American elite circles, including many people in or close to the Obama administration.

Yet something funny happened on the road to a post-American era: it didn’t happen. Even under two of the most incompetent administrations in our country’s long history, we are headed not to a “post-American” world, but more likely a “post-European” one.

The Fading of the “European Dream”

Fifty years ago, when Europe’s economy was growing faster than America’s on a consistent basis, and Asia was just emerging, the case for the continent’s ascendency seemed much stronger. But for the past 30 years Europe’s economy has been generally performing worse than that of the U.S. , not to mention rising Asian powers, including China and India.

The Great Recession hit all economies, but recently American growth rates have consistently outperformed those on the continent. By 2013 Europe was still experiencing 12 percent unemployment—a rate that exceeds ours at the height of the U.S. recession. European household debt, notes analyst Morgan Housel, has been increasing while that of American households has dropped.

The roots of Europe’s poor economy lies in large part in the very welfare state so admired by some progressives. To be sure, generous benefits have helped make Europe somewhat less unequal than the United States. But in the process Europe has become a very expensive place to do business. High taxes and welfare costs, tolerable in an efficient economy like Germany’s, have caught up with weaker, less productive countries such as Italy, Greece, and even France.

This weakness is most evident in two critical sectors—energy and technology—critical to modern economies. Europe’s much ballyhooed attempt to go “green” has raised energy costs throughout the continent. Ultimately, the effects of high energy prices tend to fall on the middle and working classes, as well as on manufacturing industries, which are are now scouring the world, including the southern United States, for lower cost alternatives.

Europe is also vastly underrepresented among the rising players in the tech world . The continent still possesses some influential industrial companies—Siemens, BMW, Volkswagen, Bayer, Royal Dutch Shell, Daimler—but it has created no European equivalent to Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Intel, or even IBM. Not one of the world’s 14 largest tech companies by revenue is based in Europe. Five are in Asia, nine in the United States. European officials have tried to curb these often intrusive and arrogant companies, but the problem lies not in overstrong American competition but Europe’s inability to grow and nurture successful young companies.

The Barrel of the Gun

It’s understandable that a continent that almost destroyed itself twice with wars in the 20th century would shy away from the use of military force. This was reinforced by decades of reliance on U.S. military might for security. This situation in turn nurtured a strong anti-military, pacifistic streak that resulted in a region with a large economy but with little to offer on the battlefield. England is the only European country to possess one of the world’s top five military budgets. Besides the U.S., by far the largest military power, the top four include China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. The three largest economies using the Euro—France, Germany, and Italy—spend one third less on defense combined than the U.S. Increasingly the only counterweight to U.S. power will be the emerging Sino-Russian alliance, which matches Russia’s still prodigious arms production with China’s almost limitless bankroll.

Demilitarization has its perils. As Chairman Mao once noted, “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Sure we should all prefer, like President Obama, to employ “soft power” rather than going in with guns blazing a la George Bush. Yet the world is still full of well-armed people who don’t play by such civilized rules. A hard-baller like Vladimir Putin knows a bluffer when he sees one and knows he can do what he wants, in the Ukraine or elsewhere, without fear of European intervention or even fear that the E.U. might help arm Kiev’s forces. Similarly, Jihadis have learned that you can do what you want to Europeans, knowing that some countries—notably France, Germany, Spain and Italy—will willingly pay ransoms to free their citizens. Kidnap a German and get rich; do it to an American, Brit or, god forbid, an Israeli, and there’s eventually hell to pay.

The Demographic Disaster

Europe’s biggest problem, however, happens inside the boudoir. Along with Japan, Europe has pioneered low fertility. European countries average a fertility rate of 1.5, well below the 2.1 children per family needed to replace their population.

The problem is most acute in Italy, Spain, and, most important, Germany. The number of German babies born annually has dropped below the levels at the turn of the last century. Not surprisingly the U.N. expects Germany’s population to drop 9 percent by 2050. Germany may have fewer children than it did in 1900, but Spain’s total number of births has dropped well below the rates of 1858, and may match those of the 18th century.

This reflects something of a hangover from the disasters inflicted by Europeans on themselves in the last century. After decades of war and conflict, notes historian Tony Judt, Europeans simply wanted peace and quiet. In post-war Europe, every subsequent generation has been a “me generation,” focusing less on family and religion and more on material goods and financial security. Today Europe is one of the most irreligious places on the planet; there are more atheists in Germany, by some counts, than in the entire United States, a country with nearly four times as many people.

To maintain their workforces and create new consumers, European countries have by necessity made a priority of bringing in more immigrants. By 2025 Germany’s economy will need six million additional workers; this means 200,000 new migrants every year to keep its economic engine humming, according to government estimates . The situation gets worse from there, and by 2050 Germany’s overall workforce (PDF) is expected to drop 30 percent below 2010 levels, reducing it from 54 to 38 million. In the same time period the American workforce is expected grow by an additional 35 million workers.

For years, Germany and other western European countries have depended on newcomers from Turkey and other Islamic countries to drive their economy. But Islamic migration is widely believed to have failed to deliver workers with enough skills, not to mention creating ever more dire cultural and social divisions. Concerned about Islamic immigration, Germans are now relying , as they did back in the ’60s, on the diminishing pool of skilled workers from rapidly aging states such as Spain and Italy, as well as from eastern Europe. These economically beleaguered countries have become a major source of new migrants to Germany, numbering roughly one million in 2011, a 20 percent increase from the previous year.

In the process, much of southern and eastern Europe is gradually depopulating. By 2050, Bulgaria is expected to lose 27 percent of its population, while Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania are expected to lose more than 10 percent of theirs. By 2050 the populations of almost the all of Eastern Europe will fall, according to recent projections.

Then there is Europe’s rapidly aging population, a natural product of low birth rates, which also imposes enormous burdens on the region’s economy. A proposal by German Chancellor Angela Merkel would impose a one percent income tax as a “demographic reserve” to make up for rising pension costs. “We have to consider the time after 2030, when the baby boomers of the ’50s and ’60s are retired and costing us more in health and care costs,” explained Gunter Krings, who drafted the new proposal for Germany’s ruling Christian Democrats.

Ultimately the next generation will be the biggest losers in Europe’s decline. Even though birthrates are very low, those young people now entering the workforce face extraordinarily high levels of unemployment ranging 20 percent and higher in countries such as Spain, Greece and France. No surprise that Europe’s young are widely described as “the lost generation.”

Political Chaos

Europe’s current political crisis has spawned a new level of political uncertainty most clearly seen in the rise of radical new parties—such as Greece’s Syriza—on both right and left. Two forces driving this shift in political balance have been immigration and a growing grassroots rebellion, such as has emerged in Greece, over EU budget and regulatory policies. In Spain, for example, the fastest rising party, Podemos, borrows directly from Syriza’s brand of quasi-Marxist radicalism.

But most of the thunder in other parts of Europe comes from the right. Many Europeans have come to see the EU not as a great unified superstate but instead as an oppressive, unelected, despotic power. The “common European home” dreamed of by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev is becoming a ramshackle collection of apartments, with neighbors who increasingly don’t get along and look elsewhere for succor.

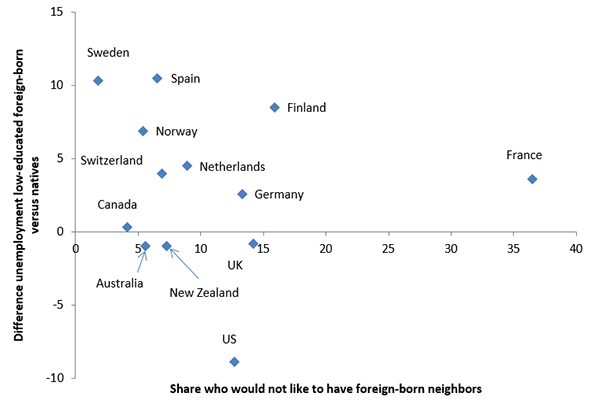

Another key driver of opposition from the right is the EU’s generally lenient view about immigration. Despite their growing dependence on immigrants, Europeans are increasingly resentful of the newcomers, particularly those from Africa and the Middle East. Some two thirds of Spaniards, Italians, and British citizens, according to an Ipsos poll, believe there are already “too many immigrants,” while majorities in Germany, Russia, and Turkey also hold negative views about newcomers in their midst.

In France the long-standing fear of losing control of national destiny has combined with growing fear over immigration, stoked by the recent terrorist incidents there. This has allowed the far right National Front’s Marine Le Pen to emerge as an unlikely front runner in the next race for president. The rise of the United Kingdom’s Independence Party stems from a similar concern about threats to Britain’s sovereignty as well as angst over immigration, particularly among working and middle class voters. Even countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands, once considered paragons of liberalism, have seen the rise of similarly minded rightist movements.

Back to Bipolarity

Buffeted by a weak economy and a welter of social ills, the aforementioned visions of Jacques Attali and American Europhiles now seem like wishful thinking, if not delusional. In reality in everything from culture and high tech to military prowess, the continent is rapidly becoming a peripheral global power at best. Only Russia, the most powerful military power and the continent’s primary source of energy, seems to have seen the light. President Putin has made this clear as he develops closer ties to China, with whom he shares an authoritarian philosophy.

Other countries on the fringe of the continent, such as Greece and Serbia, also are looking increasingly at Russia, and its emergent Chinese alliance, rather than the E.U. Chinese plans for new bullet trains to Central Asia and eastern Europe could further enhance the Middle Kingdom’s linkage to Eurasia and central Asia.

“So what about us?” Anglo-Americans (culturally if not ethnically) may ask. In a globalized world that speaks and writes in English, the Anglosphere—comprising both the U.K. and its various colonial offspring, including the United States—retains some natural advantages. This is where the most elite colleges and universities are located, and where the top financial, technology, and key business service firms are concentrated. Equally important, the Anglosphere also controls much of what the developing countries will most need in the future—food—through the unsurpassed fecundity of the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Demographics and a unique ability to absorb a wide range of immigrants make the Anglosphere economically and demographically more vibrant than Europe. By 2050, the Anglosphere will be home to upwards of 550 million people, the largest population grouping outside China and India. English-speakers may not straddle the world like the 19th century empire-makers, but they are likely to remain first among equals well into the current century.

Ultimately, the various countries of the world will have to choose between the Anglosphere and the Chinese-led authoritarian alliance. This will become something of a new version of the Cold War (but with China not Russia in the lead position), with each bloc seeking to win influence across the world. Anglophone India and Japan, for example, may choose the Anglosphere due to democratic traditions and a feeling of foreboding about a future forged by Chinese economic and, increasingly, military power.

On the other hand, Latin American nations like Brazil and Argentina may consider “yankee imperialism” a greater threat to their autonomy and choose instead to embrace the Middle Kingdom and its Russian ally. This may also hold true for much of Africa, where China is making deep inroads. The Chinese-led New Development Bank and its $40 billion “Marshall Plan” for infrastructure in developing countries represents a bold move to secure ever more influence in the emerging world order.

In this bipolar world forged in the context of U.S. vs China competition, Europe will likely be a bit player, wooed by both but essential to neither. In the 21st century, the road to power will not run through Paris or Berlin but through Beijing and Washington. Like the great leaders of the post-war era, American politicians and statesmen need to acknowledge the new reality of the post-European world and begin to address its implications.

This piece first appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.