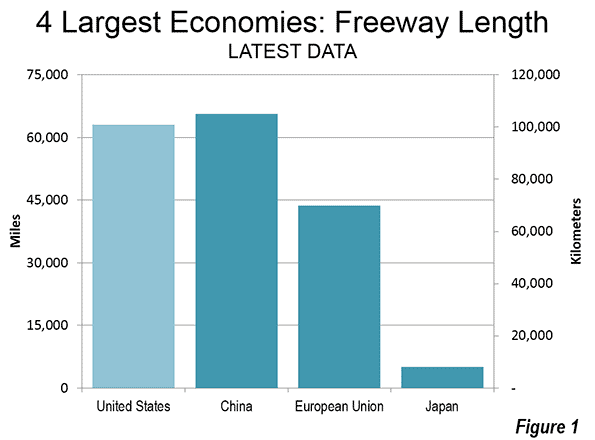

After years of closing the gap with the United States, China built enough freeways in 2013 to amass the greatest length of freeways in the world. Between 2003 and 2013, China expanded its national expressway system, with interstate (motorway in Europe) standard roadways from 30,000 to 105,000 kilometers (18,000 to 65,000 miles). This compares to the 101,000 kilometers (63,000 miles) in the United States in 2012. China’s freeway system is also longer than that of the European Union, which was 70,000 kilometers in 2010 (43,000 miles) and Japan (8,000 kilometers or 5,000 miles) as is indicated in Figure 1 (Note 1). The ascent of China is evident across the spectrum of transport data, both passenger and freight.

A review of transport statistics in the four largest world economies (nominal gross domestic product) shows considerable variation in both passenger and freight flows. It also reflects the rapid growth of China. Generally comparable and complete data is available for the European Union, the United States, China and Japan.

Passenger Travel

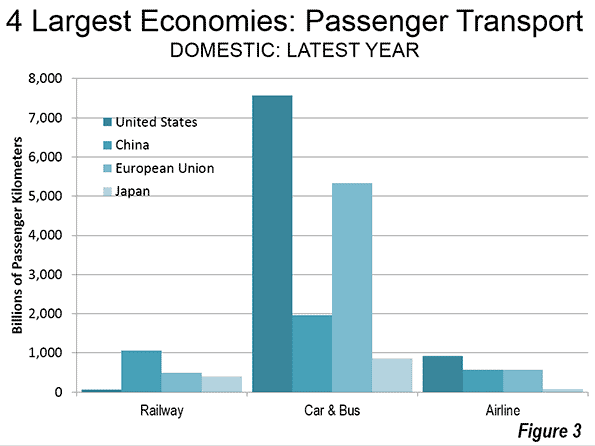

All four of the world’s largest economies rely principally on roads for their passenger transport. The United States continues to lead in road volume (in passenger kilometers, see Note 2) by a substantial margin, followed by the European Union. In the United States, automobiles account for 83 percent of domestic passenger travel, which compares to 76 percent in the European Union and 58 percent in Japan. China’s combines automobile and bus data, which makes it impossible to obtain automobile comparisons with the other three economies.

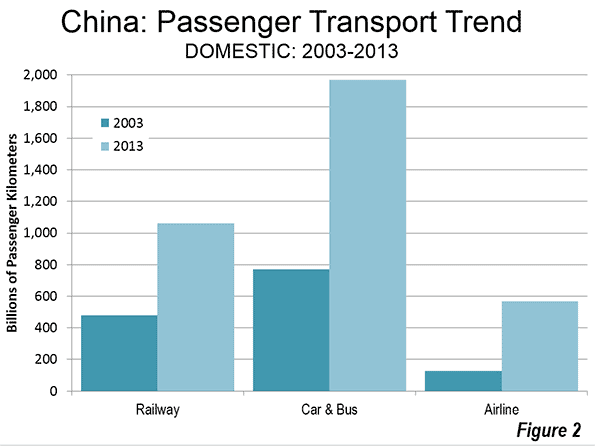

Road travel increased more than 150 percent between 2003 and 2013 in China. Yet roads have barely held their market share as China has built new world-class airports, such as Capital City in Beijing, Baiyun in Guangzhou and many others. Over the same 10 years air travel has increased 350 percent. Meanwhile, China has built the world’s most extensive high-speed rail system and has experienced healthy rail travel growth. Yet, despite this, passenger rail’s market share has dropped from 35 percent to 29 percent over the period (Figure 2).

China is dominant among the four economies in passenger rail volumes, with its 1.05 trillion annual passenger kilometers (0.65 trillion passenger miles) accounting for more than 2.5 times the rail travel in both the European Union and Japan. US rail travel is no more than 1/20th that of China (equal to the road travel volume in the state of Arkansas).

The United States continues to lead in a domestic airline travel, with a volume approximately 60 percent greater than those of the European Union and China. China trails the European Union by only two percent and with its growth rate seems likely to assume the second position before long (Figure 3).

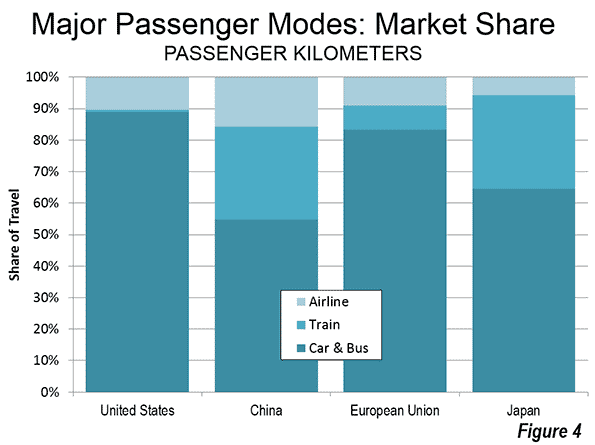

Passenger travel market shares are indicated in Figure 4.

Freight Transport

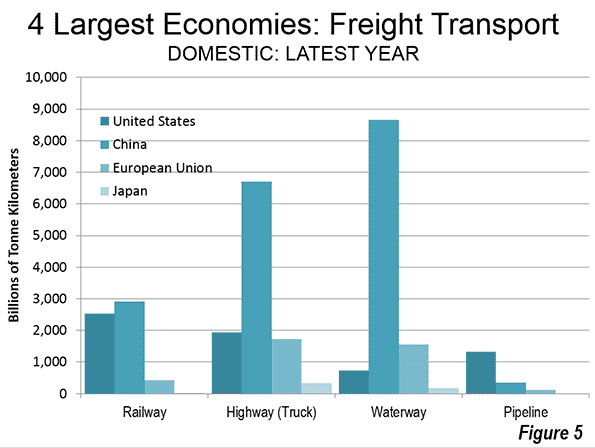

After having led the world in rail freight volumes in recent decades, the United States has recently yielded the title to China. In 2013, China moved nearly 3 trillion tonne kilometers (Note 3) of freight by rail, compared to the US total of 2.5 trillion (2012). It may be surprising to find out that Europe, with its extensive passenger train system moves so little of its freight by rail. However, the European Union moved approximately 60 percent less of its freight by rail. However, much of the capacity of the EU’s rail system is consumed by passenger trains, leaving little for freight. This is despite a policy commitment in the EU to substantially increase the rail freight market share relative to trucks. As a result, in Europe, the freight trains are "on the highway" (see Photo below). China has been uniquely successful among the world’s economies in developing both a world class freight rail system and a world class passenger rail system. One of China’s early objectives in developing its high speed rail program was to free space for its large freight train volumes.

Caption: Trucks on the A7, north of Barcelona (by author)

Among other nations, only Russia can compete with China and the United States in rail freight, having moved approximately 2.2 trillion tonne kilometers in 2012.

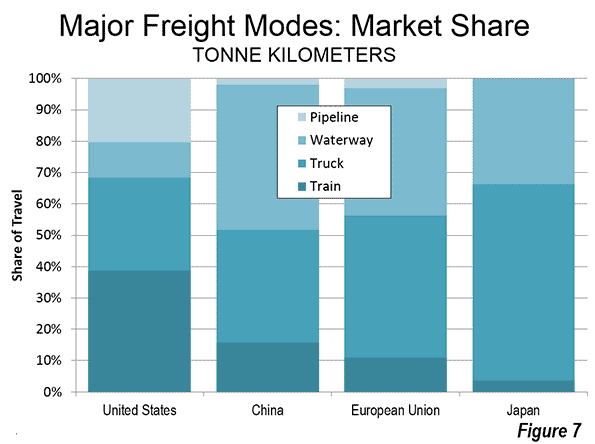

Rail freight remains by far the most important in the United States compared to the other three largest economies. Rail freight continues to carry more tonne kilometers in the United States than trucks. The situation is much different in Europe, where trucks carried four times the volume of freight rail. Rail freight is even less significant in Japan, where trucks carry more than 15 times the volume of rail freight.

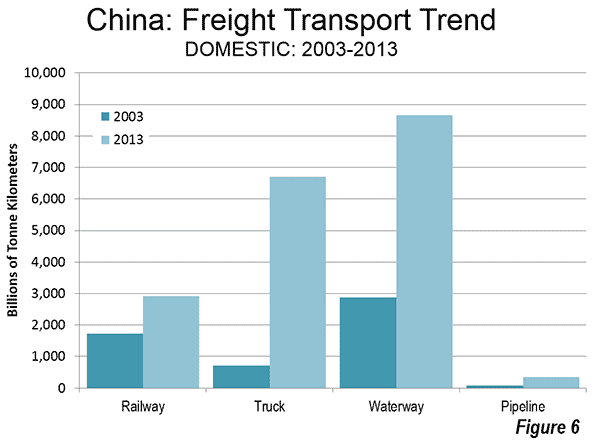

One possibly surprising fact lies with the substantial increase in China’s truck volumes over the last decade. China now has a volume of truck traffic that is four times that of trucks in either the European Union or the United States.

In 2003, trucks carried 60 percent less of the nation’s metric tonne mileage than freight rail. By 2013, that had been reversed with tracks carrying 130 percent more volume than freight rail.

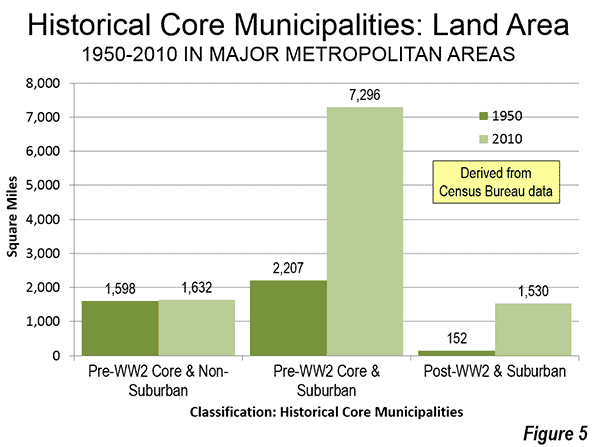

However China’s dominance is even greater in water borne freight, at nearly 6 times the European Union volume and more than 10 times the volume of the United States (Figure 5). Even so, China’s largest freight volumes are carried on waterways, such as the Yangtze River. Over the past 10 years waterway volumes tripled. It is even expected that there will be a significant increase in shipping on the ancient Grand Canal (Figure 6).

Freight market shares among the major modes are shown in Figure 7.

India

Another of the world’s largest economies, India, also relies heavily on roads. According to the World Bank 65 percent of the freight and nearly 90 percent of passengers are carried by roads in India, though late detailed data is not available. Yet India also has the largest passenger rail usage in the world. Only China is close, and the two nations have been near equal, at least over the last decade. In 2003, China trailed India by seven percent in passenger kilometers by train. Complete Indian Railway data for 2013 is not yet available. However, if the average trip length in 2013 was the same as in 2012, China will have moved to within two percent of India’s passenger rail volume. Both nations are far above Japan and the European Union, ranked third and fourth, and almost 90 percent above Russia, which has a reputation for high passenger rail volumes.

The Future

With economic growth in China slowing (though still at rates that would satisfy virtually any other nation) its transport growth of the past decade seems likely to moderate. On the other hand, the other large emerging economy, India, which has substantially trailed China, could assume a Chinese trajectory. The newly elected Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is committed to economic advance and infrastructure development. Market facilitating policies like those that have propelled China (see the late Noble Laureate Ronald Coase and Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist), could lead to a similar story about India in a decade or two.

——

Note 1: The latest data on international transport varies by year, even within nations (such as the United States). This analysis compares the latest data, which is 2012 (Europe and Japan), 2013 (China) and the United States (2011, with some 2009). This latest years available permit comparing the general scale of differences and, particularly in the United States, changes from the earlier data are likely to have been modest, as a result of the Great Financial Crisis and the great economic malaise that has followed. The principal data sources are the Bureau of Transportation Statistics in the United States, the National Bureau of Statistics in China and Eurostat for the European Union and Japan.

Note 2: A passenger kilometer (or passenger mile) is the distance traveled times the number of passengers. Thus, a car going 5 kilometers with one passenger produces 5 passenger kilometers. With two passengers, there are 10 passenger kilometers.

Note 3: A tonne kilometer is a metric tonne (2.204 pounds or 1,000 kilograms) of freight times the number of kilometers traveled. The US ton (short ton) has 2,000 pounds or 907 kilograms.

—-

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Grand Canal in Suzhou (by author)