No city in the world is so misunderstood by analysts and the press. It is commonly asserted Chongqing is the largest city in the world. In reality it barely makes the top 50, ranking 47th.

Cities (Shi) in China are Regions and Mostly Rural

It is fundamentally a problem of semantics and a failure to comprehend the nuances of urban geography in China. The country is divided into provinces and their equivalents, which are in turn, divided into prefectures, most of which are "shi," "Shi" translates into English as "city." However, shi are completely different from any English conception of a city as "an inhabited place of greater size, population, or importance than or village" (per Merriam Webster).

There approximately 300 shis and other prefectures (sub-provincial jurisdictions) in China. In contrast, there are approximately 10 times as many sub-state jurisdictions (counties) in United States, which has a land area slightly larger than that of China. China’s shi and other prefectures are thus very large. They are really more like regions in English. Virtually all shi are predominantly rural, rather than urban in their land use.

Reporters often marvel at the many cities in China of more than 1,000,000 population. Yet many of these are nothing more than broad expanses of rural areas without large urban settlements. Take, for example, Bazhong, a "shi" of 3.3 million residents in Sichuan province. The largest urban settlement occupies just 5 square miles (13 square kilometers), roughly the same land area as Goodland, Kansas (a city of fewer than 5,000 residents). Bazhong shi’s population is spread across a virtually 100 percent rural landscape of 4,700 square miles (12,300 square kilometers).

Chongqing in Context

Chongqing is a shi, and is administered as a province by the national government, as also are Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin. The province of Chongqing covers 32,000 square miles (82,500 square kilometers). This is nearly equal to the land area of Austria and more than the area of the state of Maine. No city in the world is as large as Austria.. The New York urban area comes the closest to Chongqing’s size at 4,500 square miles (11,600 square kilometers), one-seventh the land area of Chongqing.

Not a Metropolitan Area

Nor is it appropriate to consider the province of Chongqing as a metropolitan area (labor market). It is simply too large for that. Commuters from the Chongqing’s "Southeast Wing" would have to travel up to 5 hours, mainly on the China’s 75 mile per hour (120 kilometer per hour) freeway system to reach work in the Chongqing urban area. From the outer reaches of Chongqing’s "Northeast Wing," travel times could exceed 8 hours, again largely by 75 mile per hour freeway.

A Largely Rural, Not Urban Province

The province of Chongqing is predominantly rural yet The Guardian persists in telling us that "Chongqing is the fastest-growing urban centre on the planet. Its population is already bigger than that of Peru or Iraq." Not so. The 2010 Census of China placed the province of Chongqing’s population at 28.8 million, smaller than both Peru and Iraq and with fewer people than in 1990. The urban center (genuine city) of Chongqing does not reach a quarter the size of either Peru or Iraq.

The Guardian is by no means alone. Time magazine cluelessly fawned "Virtually overnight, Chongqing has become the largest city not only in China, but in the world," Wired similarly misfired with indicating in a 2008 article that Chongqing (at 32 million population) was the "fastest-growing urban center on Earth." For all the supposed growth, not a soul was added to Chongqing province during the 2000s, as is described below.

Not all media outlets, however, have been captured by the same fallacy as The Guardian, Time, Wired and many others. To its credit, the BBC went to considerable lengths to correct this and similar errors about the population of Chongqing. An Atlanticarticle also parsed the issue well.

Losing Population

In reality Chongqing lost 1.7 million people between 2000 and 2010, 5.5 percent of its population. This is significant. By contrast, the municipality of Chicago lost 6.9 percent over the same period, a loss that was considered devastating. It is not surprising that Chongqing is losing population, given its principally rural nature. Much of rural China is emptying out, as people migrate to the cities for economic opportunity (which is the very purpose of cities), just as they have done in previous decades and the last two century throughout higher income nations. Every year over the past decade, the province experienced an annual decline of 170,000, not the half-million increase reported by The Guardian. The actual urban center (not the imaginary urban center reported on by The Guardian) is gaining in population, but nothing like "half a million" per year.

The Genuine City of Chongqing

There is, however, a genuine city of Chongqing. Surprisingly reminiscent of Pittsburgh, Chongqing is it nestled among elongated folded mountains that are near duplicates of those near the Pennsylvania city. The city is at the confluence to two rivers, the Yangtze and the Jialing. Like the Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet, Chongqing’s has an attractive open space at Chaotianmin where the two rivers meet. Finally, as in Pittsburgh, there is an impressive, high rise central business district behind the open space. This is the best example in China of a monocentric central business district typical of many US cities (downtown Shanghai and Nanjing are similar, but more spread out).

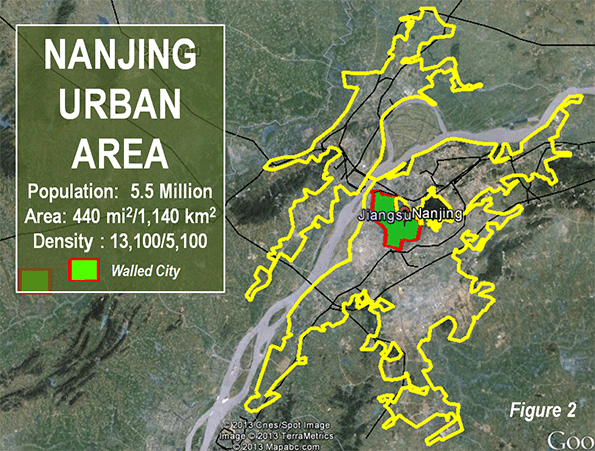

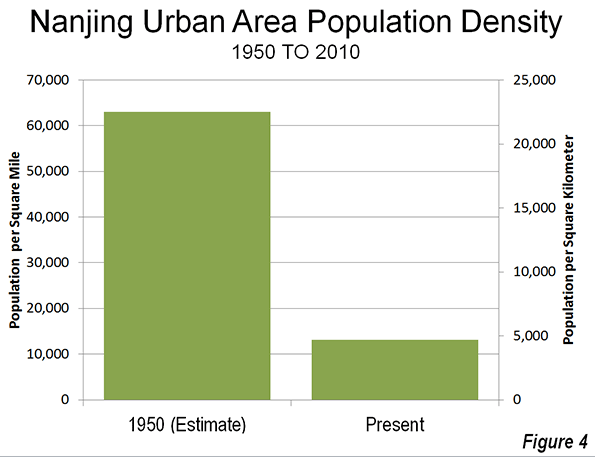

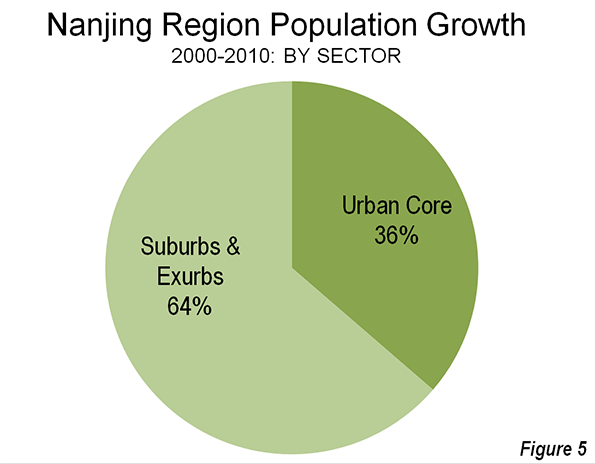

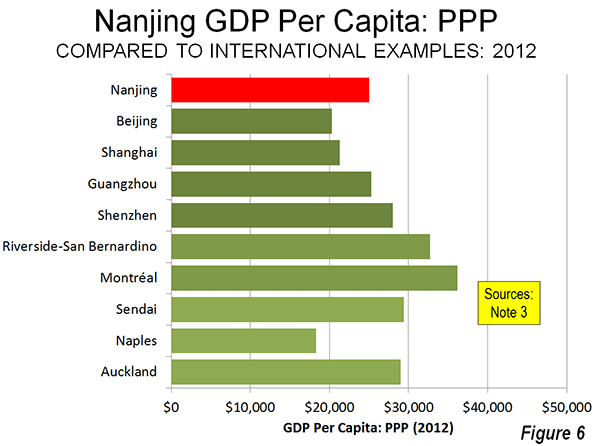

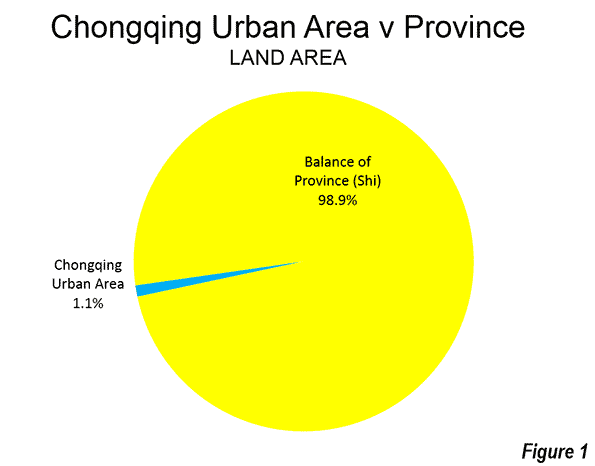

The Chongqing urban area covers little more than 1/100th of the province’s land area (Figure 1) and contains less than one-quarter of the population (Figure 2). Yet the Chongqing urban area is still large. According to the 10th Annual Edition of Demographia Urban Areas, Chongqing has a 2014 population of 6.8 million living in a land area of 340 square miles (890 square kilometers). The urban population density is 19,600 per square mile (7,700 per square kilometer), which is about one third higher than the larger urban area average of 14,900 per square mile (5.700 per square kilometer) found across China. This is more than double the density of the Paris urban area, triple the density of the Los Angeles urban area and six times that of Portland.

The "One Hour Economic Circle:" The Future Metropolitan Area

Chongqing’s administration has a vision of a much larger city. The urban plan is concentrated on the "One Hour Economic Circle," defined as within "one hour’s driving distance." This area includes 23 of Chongqing’s 40 divisions (counties and urban districts, or qu’s), with a land area of 11,000 square miles (28,600 square kilometers), more than 1.5 times the size of the Paris metropolitan area (aire urbaine) and slightly larger than New York. The 2010 census counted a population of 17.6 million in the One Hour Economic Circle, but most of it still rural. Outside the One Hour Economic Circle, in what is called the "Northeast Wing" and the "Southeast Wing," the rural influence is even greater.

The intent of the urban plan is to broaden the economic influence of the urban area. This would involve substantial increases in economic interchange (principally commuting) with the balance of the One Hour Economic Circle, now decidedly rural.

Within the One Hour Economic Circle, the large rural population suggests the potential for in-situ urbanization could also contribute to economic growth as migration, as rural residents are afforded opportunities to adopt urban lifestyles (as has occurred in Quanzhou and other urban areas, especially in the province of Fuzhou).

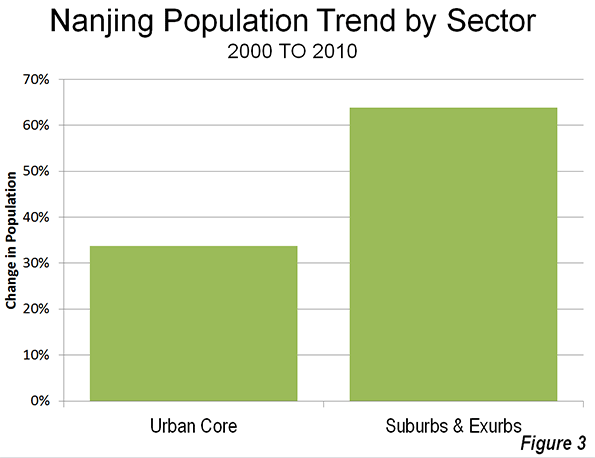

Population Trends 2000-2010

The divisions (qu) that encompass the urban area are growing, even though the core is losing (Yuzhong qu). In contrast, the metropolitan area had a population of 8.0 million in 2010, up 19 percent from 2000. This is not particularly rapid growth for China. Nearly 20 metropolitan areas grew twice as fast from 2000 to 2010. Nearby Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan, grew 2.5 times as fast as Chongqing.

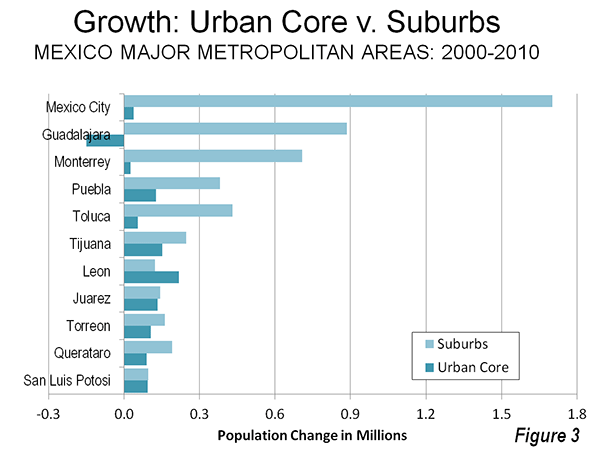

Outside the metropolitan area, the One Hour Economic Circle experienced a population loss of 12 percent. As a result of this loss, the One Hour Economic Circle had only a negligible population increase of 0.1 percent between 2000 and 2010 (Figure 3).

The Future

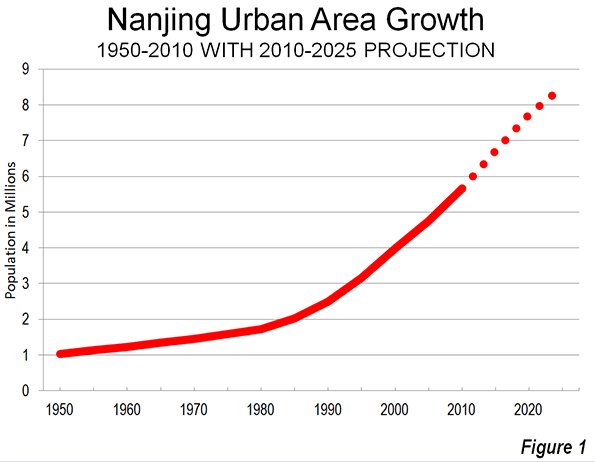

At the presently projected United Nations growth rate, the Chongqing urban area would add nearly one quarter to its population by 2025. But under this pattern Chongqing will barely hold its own, but remain in the top 50 world urban areas. Yet, the city has grand plans. There are nationally and locally designated economic zones, and lower business costs encouraging commerce to move west in China. As a province and urban area directly administered by Beijing, Chongqing could be positioned for both strong population and economic growth. Yet, it remains an open question whether Chongqing will emerge as one of China’s major growth centers.

—————-

Note: Shi are divided into county level jurisdictions, such as qu (urban districts), counties (rural districts) and count level shi.

——-

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Downtown Chongqing (by author)