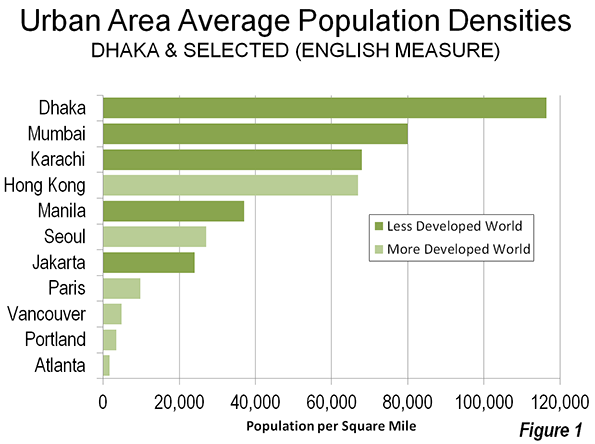

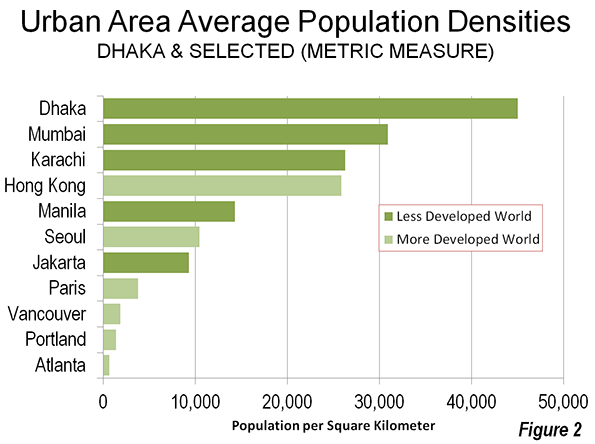

A few weeks ago, we suggested that Hong Kong was the "smart growth" ideal, for having the highest urban population density in the high income world. But, if you expand the universe to the poorer, developing countries, Hong Kong barely holds a candle to Dhaka. Dhaka’s 14.6 million people live in just 125 square miles (325 square kilometers). At more than 115,000 people per square mile (Figure 1), or 45,000 per square kilometer (Figure 2), the capital of Bangladesh is nearly 75 percent more dense than Hong Kong.

The Ultimate in Average Urban Area Density

None of the world’s megacities comes close to Dhaka’s population density. Mumbai is about one-third less dense, despite its reputation as crowded and congested. The only other megacity (minimum 10 million population) more than one-third as dense as Dhaka is Karachi. Twenty three other megacities fall at least two-thirds short of Dhaka’s density (such as Jakarta, Seoul and Paris). New York’s core, Manhattan, is 40 percent less dense, and the New York urban area does not reach 1/20th of Dhaka’s density

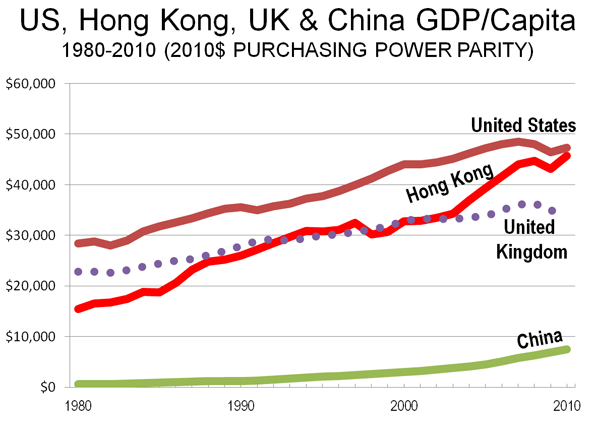

No city in the world uses land so efficiently as Dhaka. But this comes at a price. With an urban area ranked among the 20 most populous in the world, Dhaka’s average income is so low that it does not even place in the top 100 metropolitan area economies as measured by the Brookings Institution. Thus, the world’s most dense urban area is among the least economically productive. Brookings rated the principally suburban and exurban Hartford metropolitan area number one, with an urban density approximately 1/100th that of Dhaka, Hartford includes the old core city; but as well as the much more substantial primarily suburban or even exurban areas.. Hartford is among the least dense urban areas in the world, at half as dense as Portland and one-fourth as dense as Los Angeles. So much for the illusion that urban density and productivity are joined at the hip.

Despite Dhaka’s hyper-density, critics complain about Dhaka’s urban sprawl. If Dhaka is "urban sprawl," then the term is meaningless. Perhaps the critics would prefer the rural poor to live in even more crowded shantytowns, or maybe better yet, that they go back home to even more desperate rural poverty. Aspiration is not a bad thing, and if that means cities with more people, covering more land area, so be it.

Not only does Dhaka have the highest average urban density, but it also has some of the highest neighborhood densities: some slum (shantytown) population densities reach 4,200 per acre, which converts to more than 2,500,000 per square mile or more than 1,000,000 per square kilometer. Estimates of the slum population vary, ranging from a quarter to 60 percent of the area population.

Dhaka in the Neighborhood

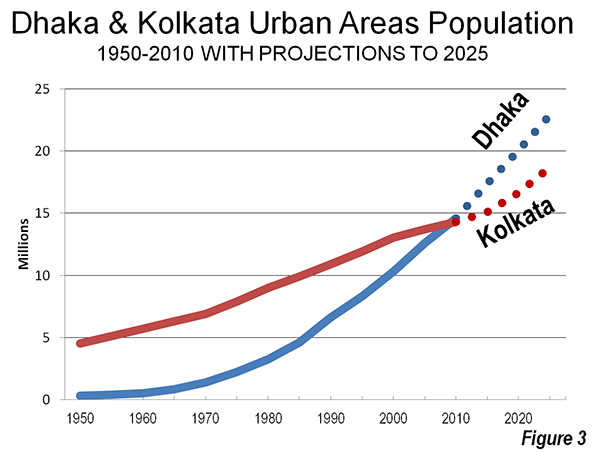

Dhaka is only 150 miles (250 kilometers) from Kolkata. Both cities were located in the province of Bengal for all but six years of the centuries long period of British rule. After the division of India and Pakistan in 1947, Dhaka was located in East Pakistan. Kolkata became the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal. For most of their histories, Kolkata was larger than Dhaka. But the Dhaka urban area has just overtaken Kolkata in population. By 2025, the United Nations forecasts that Dhaka will reach 23 million, well ahead of Kolkata’s projected 19 million (Figure 3).

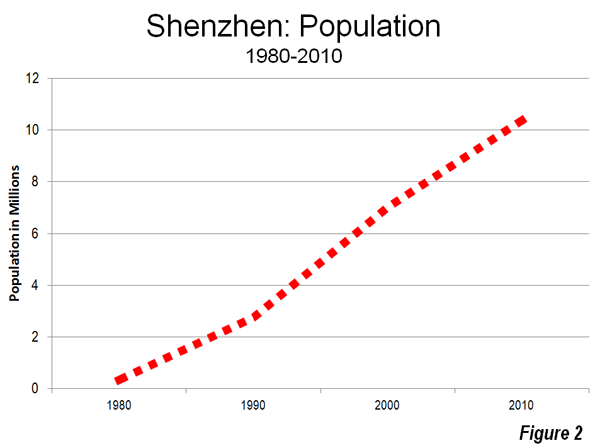

Dhaka’s growth has been spectacular. In 1970, just before East Pakistan separated from Pakistan to become Bangladesh, the urban area had a population of 1.3 million. Its population grew by more than 10 times, Dhaka growth over four decades trails only Shenzhen among the megacities, which expanded by 30 times over the same period.

The Metropolitan Area

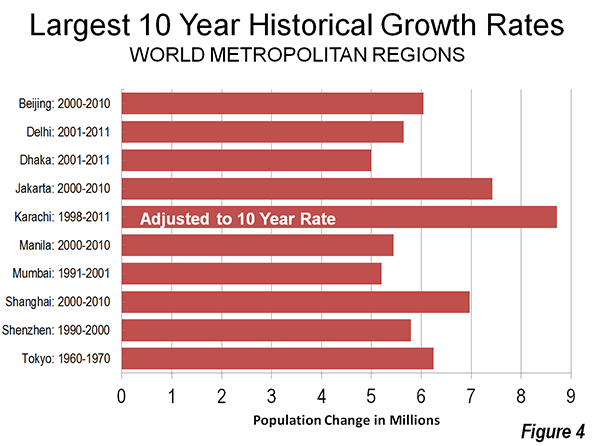

Dhaka’s metropolitan area (which includes the urban area and economically integrated rural environs) added approximately 5,000,000 new residents between 2001 and 2011. Dhaka added at least a 50 percent to its population, rising from just under 10 million population to just over 15 million during the decade (Note 1). Few, if any of the world’s largest metropolitan areas or urban areas have achieved such a large percentage population increase in a period of 10 years. Even so, Dhaka’s population added fewer people than some larger metropolitan areas over a similar period, such as Karachi, Jakarta and Shanghai (Figure 4).

Spatial Expansion

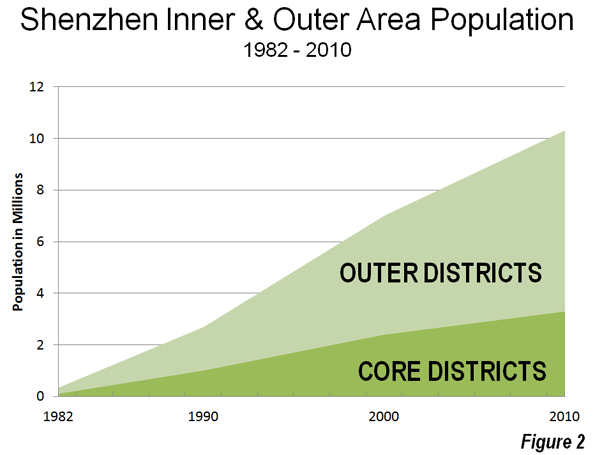

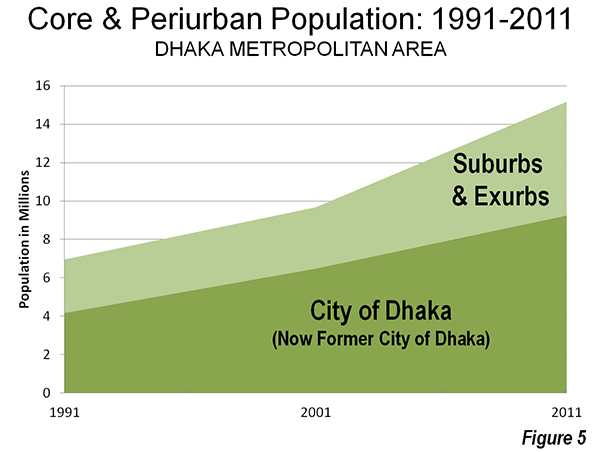

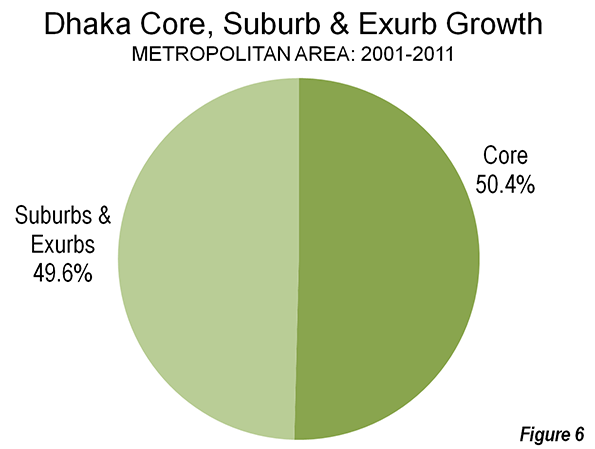

Consistent with the trend since cities escaped walls, Dhaka has been expanding spatially as its population has increased. Over the past decade, the core municipality, Dhaka, increased its population 45 percent. The suburban and exurban population increase was nearly twice as great, at 85 percent (Figure 5). The core city of Dhaka managed to capture just over one-half the population growth, but because of its larger size, the slower percentage growth rate still resulted in half the additional population being in the city (Figure 6). Dhaka thus further confirms the axiom that as cities become larger, they become less dense.

River City

Dhaka may be the worst situated urban area in the world. Dhaka is located in wetlands and virtually surrounded by rivers, some of the greatest in the world.

- Dhaka is 20 miles (32 kilometers) east of the Padma River, which is the main course of the Ganges River.

- Only a few miles north of this point, the Padma is joined by the Jamuna River, which is the main course of the Brahmaputra River.

- The Meghna River, the secondary Brahmaputra River course is 15 miles (25 kilometers) to the east of Dhaka.

- Little more than 30 miles (50 kilometers to the south is the confluence of the Padma River and the Meghna River, which flows the last few miles to the Bay of Bengal as the Meghna.

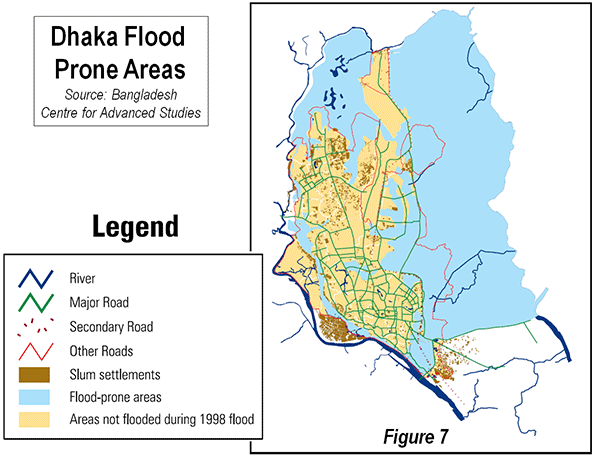

Though Dhaka is 100 miles (160 kilometers) from the Bay of Bengal (the Indian Ocean), the lowest parts of the city are little more than five feet (two meters) above sea level. This means serious flooding. The risk is illustrated in Figure 7. The extent of the risk is illustrated by the fact that the areas not prone to flooding cover less land than the urban area. That means that the necessary urban expansion will be very expensive. With the understandable exodus from rural areas to the city, the problems of high density and, particularly slums could become more acute.

A City Designed for a Metro?

The river courses and wetlands have forced Dhaka into a generally north-south orientation. The urban area averages from three to seven miles east to west (five to 11 kilometers) and is nearly 30 miles (50 kilometers north to south. The more circular development that would be expected for an inland urban area is precluded by the rivers and wetlands.

This unusual city form could serve the city well, however, as it builds its first Metro line. Stations on the planned north to south line will be within a long walk of a much of the urban area. It is hard to imagine an urban form and density more suited for a Metro. Construction is supposed to begin within the next two years.

Not only is Dhaka the largest world urban area without an urban rail system, it is also the largest without a motorway (freeway). That too will soon change, as two should be under construction soon.

Political Reform and the Future

Meanwhile, in an attempt to improve city services, the national government has divided the city of Dhaka into two. The Dhaka City Corporation has now been replaced by the Dhaka North City Corporation and the Dhaka South City Corporation. There is an increasing body of literature suggesting that smaller municipalities perform better (and spend less) than larger municipalities. The Dhaka demerger may be the first significant such move since the 1986 breakup of the Greater London Council by the Thatcher government (Note 2).

Dhaka begins the next decade undertaking significant challenges in infrastructure, economic growth and government reform. However, perhaps the biggest challenge will be to figure out where to put the additional five million people expected by the 2021 census.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

—–

Note 1: There was an undercount in the 2011 census, ranging from 3.8 percent in rural areas to 5.3 percent in urban areas. This complicates comparison between the 2001 and 2011 census data.

Note 2: Even after the subsequent creation of the Greater London Council, by the Blair government, most local functions were not transferred, remaining in the 32 local boroughs. A forced amalgamation of Montréal with suburbs was partially reversed by voter referenda in the early 2000s.

—-

Photograph: Farmview Supermarket Transit Transfer Center, on one of the urban area’s few north-south arterial roadways. (by author)