Once you understand what financial services are, you’ll quickly come to realize that American consumers are not getting the honest services that they have come to expect from banks. A bank is a business. They offer financial services for profit. Their primary function is to keep money for individual people or companies and to make loans. Banks – and all the Wall Street firms are banks now – play an important role in the virtuous circle of savings and investment. When households have excess earnings – more money than they need for their expenses – they can make savings deposits at banks. Banks channel savings from households to entrepreneurs and businesses in the form of loans. Entrepreneurs can use the loans to create new businesses which will employee more labor, thus increasing the earnings that households have available to more savings deposits – which brings the process fully around the virtuous circle.

As U.S. households deal with unemployment above 10% as a direct result of the financial crises caused by excessive risk-taking at banks, one bank, Goldman Sachs, posted the biggest profit in its 140-year history. According to Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz at Columbia University, Goldman’s 65% increase in profits is like gambling – the largest growth came from its own investments and not from providing financial services to households and businesses.

Under fraud statutes created in 1988, Congress criminalized actions that deprive us of the right to “honest services.” The law has been used generally to prosecute fraudsters and potential fraudsters – from Jack Abramoff to Rod Blagojevich – whenever the public does not get the honest, faithful service we have a right to expect.

The theory of “honest services” was used in one of the best known U.S. cases of financial misbehavior – Jeff Skilling of Enron – who has been granted a hearing early next year with the U.S. Supreme Court on the subject. Prosecutors won the original 2006 conviction on the strategy “that Skilling robbed Enron of his ‘honest services’ by setting corporate goals that were met by fraudulent means amid a widespread conspiracy to lie to investors about the company’s financial health.” The U.S. Attorney argued that CEO Skilling set the agenda at Enron. In this case, the fraud and conspiracy were means by which corporate ends were met.

Skilling’s defense attorney admitted in his appeal before the 5th Circuit in April that his client “might have only bent the rules for the company’s benefit.” The appeal was not granted – a move by the court that is viewed as an overwhelming success for the prosecution. The application of the theory of “honest services” to the Skilling case – targeting corporate CEOs instead of elected officials – has been the subject of debate which may explain why the Supreme Court agreed to hear the arguments.

Regardless of the outcome of that or other cases on the subject, the fact remains that bankers are doing better for themselves than they are for American households. This is the number one complaint we have about banks today. If I had to summarize the rest of what bothers us about banks, I would start with the fact that they are secretive. They take advantage of a very common fear of finance to convince consumers that they know what’s good for you better then you do.

Next in line is the fact that they have purchased Congress. Banks have access to the halls of power that – despite 234 years of egalitarian rhetoric – ordinary voters can never achieve. Finally, we resent banks because we are required to use their services, like a utility, to gain access to the American Dream.

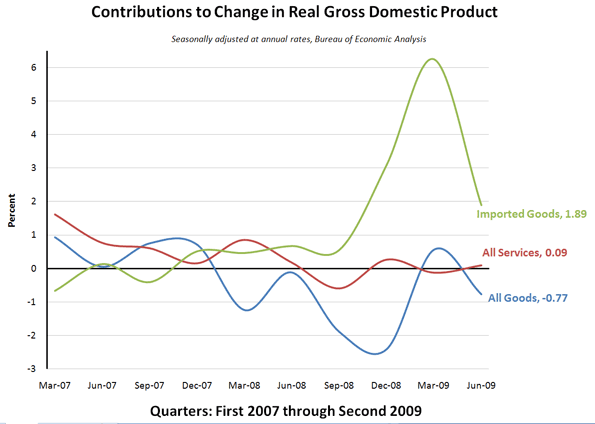

Financial services contribute about 6 percent to the U.S. economy. Manufacturing and information industries use financial services, but the industry increasingly depends on itself: recall the portion of Goldman’s earnings growth coming from using its own investment services. According to the latest data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the financial services industry requires $1.27 of its own output to deliver a dollar of its final product to users. Despite the fact that our economic reliance on financial services has been creeping up steadily since 2001, they remain one of the least required inputs for U.S. economic output – only wholesale and retail trade have less input to the output of other industries.

So, why did Congress vote them nearly a trillion dollars worth of life-support bailout money at the expense of taxpayers? Why did Wall Street get swine flu vaccine ahead of rural hospitals and health care workers? Why did they get the bailout without accountability? By making banks account for what they did with the money, congress could have 1) prohibited spending on bonuses and lavish retreats; 2) ensured improved access to credit for small and medium enterprises; and 3) provided transparency to taxpayers on who got how much and what they did with it. Need more reasons to demand honest services from a banker? Try this list:

- Congress raised the FDIC insurance to $200,000 to make depositors comfortable leaving money in banks; then the banks passed the insurance premium on to customers – including those that never had $200,000 cash in the bank in their lives and probably never will. Seriously, how much money do you have to have before it makes sense to have $200,000 in cash in a savings account earning 0.25%?

- Banks can borrow at 0% from the Fed yet they raise the interest rates they charge even their best customers. The bank I use for my company willingly lent me $10,000 last year to open a new office and approved a $7,000 credit card limit. Last month they sent me a letter saying they are raising the interest rate by +1.9 percentage point – though I have never missed a payment deadline.

- The banks can use our deposits to purchase securities issued by the Federal government, which are yielding better than 3 percent. They pay us about 0.25 percent yet still find it necessary to tack on a multitude of fees – which amount to 53 percent of banks’ income today, up from 35 percent in 1995.

For now, Brother Banker skips along as lively as a cricket in the embers. But remember this: Marie Antoinette didn’t know anything about the French revolution until they cut off her head. Matt Taibbi, in a recent Rolling Stone article called Goldman Sachs a “great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” We are at risk for leaving the virtuous circle behind and entering a vicious circle of spiraling inflation. A massive increase in government debt is being paid down by printing more money. Between July 2008 and November 2008, the Federal Reserve more than doubled its balance sheet from $0.9 trillion to $2.5 trillion. A year later, there is no evidence that they are trying to rein it in. As Brother Banker fails to provide honest services, a briar patch of a different kind may be waiting around the corner.

Susanne Trimbath, Ph.D. is CEO and Chief Economist of STP Advisory Services. Her training in finance and economics began with editing briefing documents for the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. She worked in operations at depository trust and clearing corporations in San Francisco and New York, including Depository Trust Company, a subsidiary of DTCC; formerly, she was a Senior Research Economist studying capital markets at the Milken Institute. Her PhD in economics is from New York University. In addition to teaching economics and finance at New York University and University of Southern California (Marshall School of Business), Trimbath is co-author of Beyond Junk Bonds: Expanding High Yield Markets.

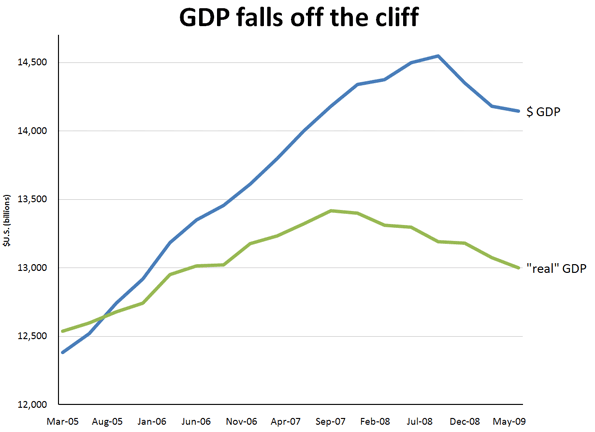

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations

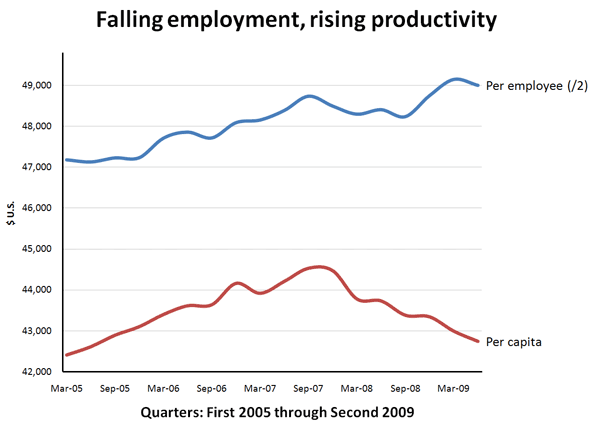

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.