I have heard Paul Krugman say that ‘the end is nigh’ so many times that it seemed like the only sensible way to think about the housing market. It was identified as a bubble, and that could only mean that it would eventually burst. A steady diet of NYT editorials and Economist charts leave you with one conclusion — this is not going to end well.

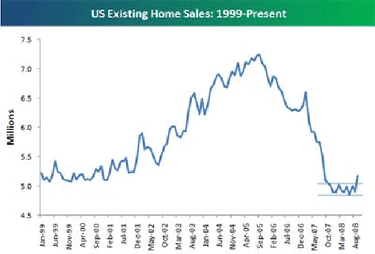

This certainly seems to be true in Phoenix. Even though I’ve lectured for years about ‘the growth machine’, how the economy in a city like Phoenix depends on building more homes, I did not expect the whole thing to collapse quite so precipitately, and with so many repercussions. The number of passengers going through the airport here is down 10% from last year; numerous restaurants, stores and other services have gone out of business, the State is trying to stare down a $3 billion deficit, the universities have fired hundreds of people—so the cycle keeps spreading like a slow motion disaster.

Also predictable is the response. Local politicians are planning to slash the State budget and get government off people’s backs, once and for all. If we used foreign phrases such as ‘chutzpah’ around here, that would have to qualify. After all, it takes balls to watch the market behave like a bunch of drunks kicking Humpty Dumpty about, and then blame government for trying to put him back together again.

Yet, at least here in Phoenix, it turns out that Professor Krugman hadn’t really got it figured out after all. As a rational man, he was distracted by the irrational exuberance of the market, the unsupportable ramping up of property prices, the NINJA loans, and the cynical exploitation of those arriving late to the party, those doomed to buy at the top of the market and be left holding fake mortgages on homes with phony values. The solutions seem simple. More oversight from Big Brother and everything can be fixed. Or, if you prefer to listen to the bizarro-world script over on AM radio, the black helicopters are about to start landing on Wall Street as the UN takes over to install European-style socialism.

Yet much of this commentary is laughably wrong. The housing market debacle was not just predictable but actually utterly unavoidable. Some of this is simply a matter of money circulating around, which as Niall Ferguson’s book The Ascent of Money makes clear, this is as old as capitalism itself. The difference now is that digital technologies have made the speed of trading and transfer shift. The same rules apply, except that everyone must work harder to keep that cash flowing.

What I now realize is that the entire economic system is based upon finding more risk. Without more risk in which to invest, the economy can’t keep moving. In other words, this wasn’t a series of calamities or errors or criminal mistakes — it is the market at work, no more, no less. And that is not going to change.

What I thought I knew is not really so. I thought a bigger banking sector was not just more mysterious but was somehow more efficient and therefore safer; after all, health insurance works best if the risks are spread across larger and larger groups. Yet in reality finance is more like a vast Ponzi scheme. We should, in fact, let Mr. Madoff out of jail, as he was doing nothing particularly wrong — his only crime was that he wasn’t being clever enough in hiding his scheme in sufficiently obscure mathematics.

What happens to the cities, towns and suburbs left devasted by the financial schemers? As James Surowiecki recently observed in the New Yorker, “banking grew bigger and more profitable but all we got in exchange was acres of empty houses in Phoenix.” So? Isn’t that a small price to pay? Given a choice, what would we rather have: a buoyant capital market and a few distant suburbs and downtown condos without any residents, or what we have today in some cities — double digit unemployment?

There are real policy issues at work here. We were taught years ago, by the Marxists no less, that the purpose of a capitalist economy is to reproduce itself and the purpose of governments is to make sure that happens. So we make credit available to people; first to buy Model Ts, then to live in Levittown, then to play golf in Cancun, and so forth. And for this to work there has to be more risk in which to invest, an endless supply of new things. Housing has served us well in this regard; people live in condos and McMansions, people sell them, people build them, people manufacture the fixtures and fittings. This is how the growth machine, particularly in places like Phoenix, works.

An economy like Phoenix is like a shark – it can’t stop, it can’t even run slow. We have to find more buyers — or perhaps we just build the homes now and fill them in the future when the population increases. Or, in line with a previous posting, we should have solved the immigration problem, and the need to sell more homes, by legalizing the Latino population and making them creditworthy.

In this sense, maybe all this focus on the Valley’s 65,000 foreclosures is a mistake. As I argued last year, perhaps they should just be turned over to rentals and let the market sort it all out; predictably, rents are now coming down in apartment complexes as more families find affordable homes to rent.

What we need is not to stop the market from repairing itself but we need to do it in a more creative way. Some of those suburbs are looking a bit down at heel, and the homes weren’t that sturdy to begin with — so let’s bulldoze them and do some serious brownfield redevelopment. Perhaps build them right, more sustainably, and less dependent on distant employment centers

We can all get back to work, we can all feel virtuous as no new desert is being bladed, the infrastructure is already paid for, the journey to work costs will be less, the density perhaps a little higher with more jobs, offices and retail located closer to the houses.

This approach will let us build more homes and get some more risk back into that market. Let’s repurpose the land. Then we can go back to business as usual, and if I was a betting man, that’s exactly what we are going to do.

Andrew Kirby is the editor of the interdisciplinary Elsevier journal “Cities.”This is his 20th year as a resident of Arizona.

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain.

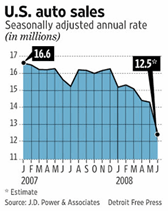

About 200 million years ago the continents began to drift apart as the globe separated into eight distinct tectonic plates. History will record that the financial tectonic plates of our world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. They have not stopped moving and the outcome of where they will end up remains uncertain. Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.

Fifty years ago General Motors owned more than 50% of the American market and automobile jobs made up one seventh of the US workforce. It was said that when GM sneezed the US economy caught a cold. GM shares now sell for less than a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now GM is about to enter bankruptcy.  The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.

The New GM will become the platform for small fuel efficient cars, hybrids, electric vehicles and experimental technologies mandated by an ever demanding government. Its shareholders vanquished, The New GM will bear no resemblance to the car company that we have known for the last 50 years. Can the Chevy Volt rescue GM? The answer is no.