Just how bad is the current economic downturn? It is frequently claimed that the crash of 2008 is the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. There is plenty of reason to accept this characterization, though we clearly are not suffering the widespread hardship of the Depression era. Looking principally at historical household wealth data from the Federal Reserve Board’s Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States, summarized in our Value of Household Residences, Stocks & Mutual Funds: 1952-2008, we can conclude it’s pretty bad, but nothing yet like the early 1930s.

But this Panic of 2008 is no picnic. And in some key areas, notably housing, it could be even worse than what was experienced in the Great Depression.

Housing: It all started with the housing bubble that saw prices in some markets rise to unheard of levels, principally in California, Florida, Phoenix, Las Vegas and the Washington, DC area. Mortgage lenders, unable to withstand the intensity of losses in these markets caused by declining prices, collapsed like a house of cards. This precipitated the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy on Meltdown Monday (September 15, 2008) and a far broader economic crisis since that time.

Before the bubble, housing had been a stable store of wealth (equity or savings) for Americans. According to federal data, the value of the US owned housing stock increased in every year since 1935. The bursting of the housing bubble, however, brought declines in both 2007 and 2008, the longest period of housing value decline since between 1929 and 1933. The value of the housing stock was down 20 percent from its peak at the end of 2008. In some markets the losses amounted to more than double this amount. By comparison, the 1929 to 1933 house value decline was 27 percent. However, only one Great Depression year (1932) had a larger single-year decrease than 2008.

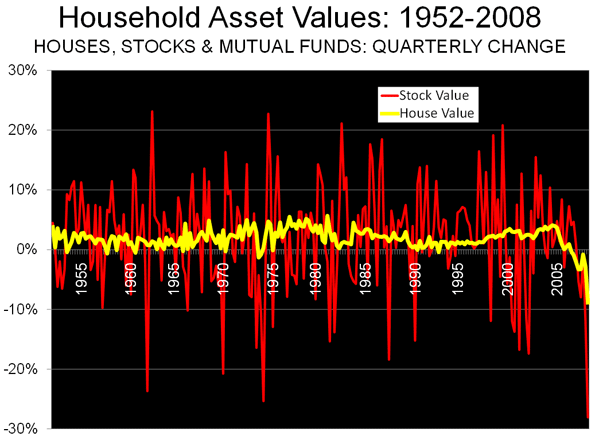

Indeed, between 1952 and 2006, the value of the housing stock never declined for more than a three month period. The bubble changed all that. The value of the housing stock has now fallen eight straight quarters. An investment that has been safe for most middle class Americans – the house in the suburbs – suddenly experienced the price volatility usually associated with the stock market, as is indicated in the chart below.

The resulting losses have been substantial. By the end of 2008, the value of the housing stock has fallen $4.5 trillion. In Phase I of the housing downturn, before Meltdown Monday, the largest losses were concentrated in the markets with the biggest “bubbles,”. But since that time the market has entered a Phase II decline, while a more general decline has characterized housing markets around the country in the fourth quarter of 2008. The decline continues.

California, the largest of all the states, has been particularly hard hit. New data for both the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas show price drops of approximately 10 percent in January, 2009 alone, as prices fall like the value of a tin-pot dictatorship’s currency. This decline, it should be noted, has spread from the outer ring of these areas – places like the much maligned Inland Empire region and the Central Valley – into the formerly more stable, and established, areas closer to the larger urban cores, which some imagined would be safe from such declines.

Sadly, there may well be some time before house price stability can be achieved. To restore the historic relationship between house prices and household incomes to a Median Multiple (median house price divided by median household income) of 3.0 would require another $3 trillion in losses, equating to a more than 15 percent additional loss. Losses are likely to be greater, however, not only in the “ground zero” markets of California and Florida but also other hugely over-valued markets, such as Portland, Seattle, New York and Boston. Of course, these are not normal times, and an intransigent economic downturn could lead to even lower house values than the historical norm would suggest.

Stocks and Mutual Funds: As noted above, stocks and mutual funds have been inherently more volatile than housing values. According to Federal Reserve data, the value of these holdings fell 24 percent over the year ended September 30. Based upon later data from the World Federation of Exchanges, we estimate that the value declined sharply after September 15, and at December 31 stood at 45 percent below the peak.

The household value of stocks and mutual funds has declined for five consecutive quarters, as of December 2008. There was a more sustained drop over six quarters in 1969-1970, although the decline in value was less than the present loss, at 37 percent. A larger decline (47 percent) was associated with the four quarter decline of 1973-1974. Comparable data is not available for household stocks and mutual fund holdings before 1952. The less complete data available indicates that the gross value of common and preferred stocks fell 45 percent from 1929 to 1933. As late as 1939, a decade after the crash, the loss had risen to 46 percent, indicating both the depth and length of the Great Depression.

The present downturn seems on course at a minimum to break the post-depression loss record with an overall decline at 55 percent as of February 20. This would correspond to a household loss of $8 trillion from the peak.

Consumer Confidence: The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index reached an all time low of 25.0 in February, down a full one-third in a month. Even with its gasoline rationing, the mid-1970s downturn saw a minimum Consumer Confidence Index of 43.2. Normal would be 100; as late as August of 2007, consumer confidence was above 100. Consumer confidence is important. Where it is low, as it is today, there is fear and even people with financial resources are disinclined to spend. Confidence is a major contributor to economic downturns, which is why they used to be called “panics.” Restoring confidence is a requirement for recovery.

Government Confidence: If there were a federal government index of confidence, it would probably be near zero. This is demonstrated by the trillions that both parties in Washington have or intend to throw at banks, private companies and distressed home owners to stop the downturn. Never since the Great Depression have things become so bad that Washington has opened taxpayer’s checkbooks for massive financial bailouts.

How Much Wealth has been Lost: The net worth of all US households peaked at $64.6 trillion in the third quarter of 2007, according to the Federal Reserve Board. Since that time, it seems likely that the housing, stock and mutual fund losses by the nation’s households could be as high as $12 trillion – $4 trillion in housing and $8 trillion in stocks and mutual funds. This is a major loss and is unlikely to be recovered soon. Yet it makes sense to consider these losses in context. Unemployment is far lower than in the 1930s, when it reached 25 percent, and the Dust Bowl is not emptying into California (indeed, more than 1,000,000 people have migrated from California to other states this decade).

Born Yesterday Jeremiahs: It is fashionable to suggest that the current economic crisis is the result of over-consumption and an unsustainable lifestyle. The narrative goes that the supposed excesses of the 1980s and 1990s have finally caught up with us. In fact, however, even with the huge losses, the net worth of the average household is no lower than in 2003 and stands at 70 percent above the 1980 figure (inflation adjusted). This may be a surprise to “born yesterday” economic analysts.

The reality is that the country achieved astounding economic and social progress since World War II. The reality remains that even after the losses we are not, objectively speaking, experiencing Depression-like conditions. Critically, the answer to the question, “Are you better off today?” in 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990 and even 2000 is “yes”. This is a critical difference with the situation in the 1930s when the country overall was much poorer, and far less able to withstand such punishing losses.

Beware the Panglossians: Even so, it seems premature to predict that the economy will turn around soon. Some Panglossian analysts predict recovery later in the year or in 2010 seem likely to miss the mark by years. Remember analysts – particularly those tied to both the real estate and stock sectors – who have discredited themselves with their past cheerleading. In addition, the international breadth and depth of this crisis cannot possibly be fully comprehended at this time. Last week the Federal Reserve predicted a declining economy over the next year.

And even when the recovery starts, it is likely to be slow because of the public debt run up to stop the bleeding. When the recovery begins, the nation and the world will have to repay the many trillions in bailouts one way or the other. This can take the form of higher taxes, inflation, rising real interest rates or, if you can imagine, all three.

How Bad Is It? Bad Enough. The present downturn is not as serious as the Great Depression. Nonetheless, the Panic of 2008 is without question, the most serious economic downturn since the Great Depression. The real question is whether the government will react as ineffectively as it did back then, and prolong the downturn well into the next decade.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”