Orlando has taken on a new “web city” form. Its dispersal over a wide geographical area allows distinct and unique pockets of culture to arise within it, a kind of archipelago of art and design. It is a microcosm of the archipelago of many Florida cities. The overall effect is marvelous, if somewhat diluted by distance, and the broad metropolitan area has come to be a proving ground for artists, architects, and urban designers. As an artist and designer commenting on these topics, the single biggest trend I have seen in the last fifteen or so years is a growing sense of maturation. What else have I seen? And, over the years, what have my observations, and those of other critics, contributed to the art scene?

In a city like Orlando, the art and design critic must have an exceptionally broad range, because the arts scene is flung between Daytona and Winter Haven, two poles that are each about 110 miles away from the city’s downtown area. The art scene in pre-World War II Central Florida consisted of a rare, purpose-built art colony simply called “The Research Studio,” where artists from the northeast wintered and pursued creativity.

Near Winter Haven, Edward Bok, retired Harvard president and publisher of the Ladies’ Home Journal, created a cultural retreat of his own. Daytona, meanwhile, attracted automotive technology aficionados to the race track, bringing with them a uniquely American appreciation of pop culture and art. The artistic geography of Central Florida reflects the artistic range of America in many ways as a whole.

More than one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s disciples relocated to Orlando as early as World War I, eying Florida’s inevitable growth potential. Few creatives sought Orlando specifically, and they gravitated here for different reasons. Jack Kerouac, for example, came to live with his sister while On the Road was prepared for publication, using Orlando as a place to escape. This escapism instinct would later inform millions of people a year, when tourism came to the area.

In the aftermath of World War II, Orlando was a sleepy railroad and citrus-shipping town. Its binary heart was born in the ’60s with the arrival of Disney. Escapism as an industry brought thousands of performers, artists, and writers to the area. Downtown Orlando today is a hub where artists and writers congregate, while the themed-entertainment industry focuses artistic talents around the southwest side of town.

As in any city, artists and designers have day jobs as well. But the Orlando area is one of the nation’s few metropolitan places of affordability and ease of lifestyle. We have artists whose work is collected nationally; artists who have works in major museums across the United States, and art events such as Snap! Orlando, a regional photography exhibition.

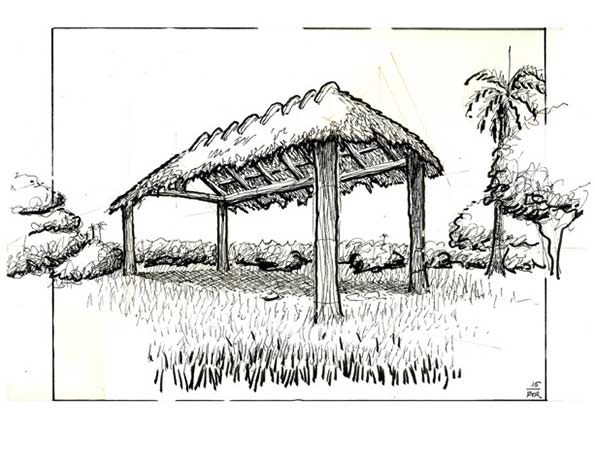

Today, these artistic pursuits are being supplemented by new efforts in a wider range of locations. West Volusia County’s mixture of Stetson University and the Museum of Art – DeLand has become an artist’s haven. The Atlantic Center for the Arts, in New Smyrna Beach, has continued to program international artists, musicians, and writers in a secluded, tree-canopied forest near the Intracoastal Waterway. In financial parlance, these creative expressions are thriving new ventures.

Art and design have always had an impact on quality of life. This is more important than ever in the twenty-first century as we re-invent the meaning of human habitation, and artists and designers articulate our current age visually. Performing arts and music also have profoundly influenced the visual arts and the notion of good design. The impact works in reverse as well: our thriving farm-to-table food scene nurtures — literally! — our creative community.

But it is the conversation about art that is key, and the critic stimulates that discussion. As Oscar Wilde said, “The only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.” I come to the role of critic as a practitioner, one who walks in the shoes of the creative individual or team. I’d rather make art than talk about it, but still, I have a few thoughts to offer on what constitutes good criticism.

Foremost, it is important to have standards, but standards are a little different than rules. Many urban designers are like artists who fret about using complimentary colors in the wrong way, overlooking the big picture. Standards of good art and design are universal, and are about getting an idea, a story, or a theme across in a satisfying or visually compelling way.

I also pay little attention to credentials. Some of the best artists and designers come to the art world without any credentials at all. In this age, credentials are everything, but they haven’t made a great deal of difference in art and design. Some of the nation’s most highly credentialed urban designers were involved in creating Orlando’s Baldwin Park, which suffers from low business occupancy and high residential turnover.

Meanwhile, the frowsy Audubon Park, just a half mile away, built in the 1940s, is a 2016 Great American Main Street Award-winner, and is bursting with independent entrepreneurial projects: coffeehouses, urban farms, an exquisite fishing gear business, and some of the best food in the city. Successful design isn’t about credentials; it is about the practical world of what works.

In the fine arts, local museum leadership has undergone a transition, and curators have been set free to show relevant, impactful work. What the curators do with this freedom will be telling. So far, they have created an annual cash prize for the best Florida contemporary artist, unleashed a world-class private art collection free to the public, extended exhibitions to a college museum, and served as juries on artist-in-residence programs. All of this has been fueling the exchange of ideas and stories.

Telling the exciting story of Central Florida art and design has been part of my good fortune. Because it is such a great story, the Association of Alternative Newsmedias has selected three stories about the Central Florida arts scene as finalists in a national competition, beating out stories from rivals such as Austin, Oakland, and Charlotte, three cities of similar size.

An experimental building or a stunning painting is nothing if it is hidden or ignored. Today, with technology and imagination pushing the boundaries, it is often difficult to have a conversation about new art and architecture. Criticism helps to frame the conversation; it sets a standard for the dialogue about what we see. It also serves the purpose of applauding good results, and pointing out results that should be good, but are not. We make our cities better by agreeing on what works.

Since coming to Central Florida in the mid 1990s, I have seen the artistic scene here mature. Experimental work, street art, and emerging talent continues to “bubble up” into the mix. In the past, the bubbles tended to pop, or to float away to places like New York City where the art would be noticed. Now, it seems that good artists are sticking around, trying to make this place better — and beginning to take us to the next level.

Richard Reep is an award-winning artist and architect who writes art and design criticism for a variety of publications. You may nominate him as Best Arts Advocate 2016 by clicking http://orlandoweekly.secondstreetapp.com/l/Orlando-Weeklys-Best-of-Orlando-Readers-Poll-2016/Ballot/ARTSampCULTURE.

Anyone visiting Central Florida can find a discussion of visually compelling aspects of the area in Reep’s Orlando Weekly column.

Photograph by the author: “Cedar of Lebanon” by local artist Jacob Harmeling graces the southern quarter of Lake Eola Park in Downtown Orlando, one of the few original artworks commissioned as part of the city’s public art program.