In this column, we often rate metropolitan areas for their performance over one year, five or at most 10. But measuring economic and social progress often requires a longer lens, spanning decades.

Nowhere is this clearer than in education, which many claim is the key to higher-wage economic growth. Yet there are two sets of numbers that need to be distinguished: those states with the highest percentage of educated workers and the states that have increased their numbers most rapidly.

On one side, the share of the population that is educated, states’ relative standings remain fairly similar to the way they were in 1970. Colorado, California, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Maryland and Virginia are all still above the national average for the percentage of the population over 25 with a bachelor’s degree, which has risen from 10.7% in 1970 to 29.6% in 2013. Massachusetts leads the nation with a remarkable 40.3% of its adult population having graduated from a four-year college. Overall, the “brainiest states” remain well ahead of their competitors in percentage terms.

But in terms of growth in the raw numbers of educated people, most of these states have lagged. Indeed their high concentrations of college graduates may reflect their slow population growth, or the lack of opportunities for people without a bachelor’s degree.

Educating The Sun Belt

The states whose populations of college grads have grown the most are almost all in the South and the Sun Belt, led by Nevada with a 1,292% increase from 1970 to 2012 in the number of residents with four years of college or more, followed by Arizona (861%), Florida (743%) and Georgia (699%).

Although they mostly still lag the best educated states, their large additions of educated workers appears to be transforming these former backwaters into centers of advanced industry and commerce. Since 1970, Texas has increased its population of college graduates by 555% while North Carolina’s surged 659%; in contrast, New York’s educated workforce expanded by 247% and Massachusetts’ by 341%, lagging the national average of 397% growth. California, whose economy grew rapidly through this period, was a shade above that with a 402% expansion in its population of college grads.

The dichotomy is also pronounced when looking at the growth in the population of those with three years of college or more, including community college and certificate programs. Since 1970, for example, South Carolina expanded its population of such people by 746% and Texas by 592%; in contrast Massachusetts’ ranks of “some college” grew by 213% and California’s by 304%. Much of the growth among the leading states was tied to rapid overall population growth due to in-migration, particularly in states like Arizona and Nevada, which was accompanied by relatively rapid job growth.

Brain Centers And Slower Growth

The most educated states by percentage of college graduates are on the East Coast — Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland, Virginia, New Jersey — with the exception of Colorado. Many of these states also boasted among of the highest concentrations of college grads in 1970 (Colorado ranked first then with a 14.9% concentration). But with the exception of Virginia, since then the growth in the raw number of educated workers in these states has come at a slower rate than the Sun Belt states, amid their rapid population expansion. For example, since 1970 Connecticut’s population of college grads grew 282%, the fourth lowest rate in the nation and roughly half that of Texas’.

Some might think that states with a higher proportion of educated workers would do better at creating new jobs. But since 1991, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment in both Massachusetts and New York has grown at 0.4% annual rate, and 0.8% in California. In contrast, Arizona’s annual job growth averaged 2.4% and Texas 2%.

This suggests that having a high percentage of educated people is not enough to grow a jobs-rich economy, particularly if, as Robert Reich suggests, the demand for educated workers in the U.S. has dropped since 2000. It might seem tautological, but expanding economies attract new educated workers.

The Changing Face Of Poverty

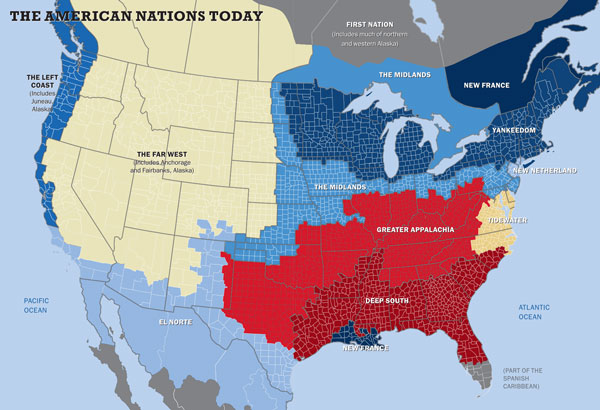

In 1959, the South was the poorest region in the country, with a poverty rate of 35.6%. By 1979, in the wake of the federal War on Poverty and strong economic growth, the poverty rate in the South had fallen by more than half, to 15.3%; by then, New York and Texas had roughly comparable poverty rates. (Note that I am not suggesting a linkage to the education trends discussed above, which mostly cover a later period.)

The shift in the geography of poverty was underlined a few years ago when the Census released a new estimation of how to track it, the Supplemental Poverty Measure. (It takes into account the cost of a broader range of necessities than the standard measure, which is limited to food. It factors in geographic differences in housing costs, adds noncash benefits like nutrition assistance and housing subsidies to families’ incomes and subtracts taxes, child support payments and out of pocket medical expenses). The SPM placed 2 million more Americans below the poverty line as of 2012 than the standard measure; it dropped the poverty rate for those living in rural areas and raised it for those in metro areas and heavily urbanized states like California and New York. For the years 2010-12, California’s poverty rate jumps from slightly above average by the standard measure (16.5%) to the highest in the nation under the SPM (23.8%), followed by the District of Columbia (22.7%). Longtime laggard Mississippi, which ranks second worst in the country under the standard measure at 20.7%, falls back to the national average of 16% under the SPM, better than New York at 18.1%.

Long-term income growth statistics over the same timespan as our education data also tell an interesting story. U.S. per capita incomes have risen 77% in inflation adjusted dollars from 1970 to 2013, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The leader has been North Dakota, with a 160.4% jump to $53,182. Much of it seems tied to the energy boom – incomes have jumped 51% alone since 2000 — but it’s more than that. Its neighbor South Dakota, where oil production is much less important, ranks third in per capita growth over that span at 125.9%, as it built up a powerhouse financial services industry by loosening regulations.

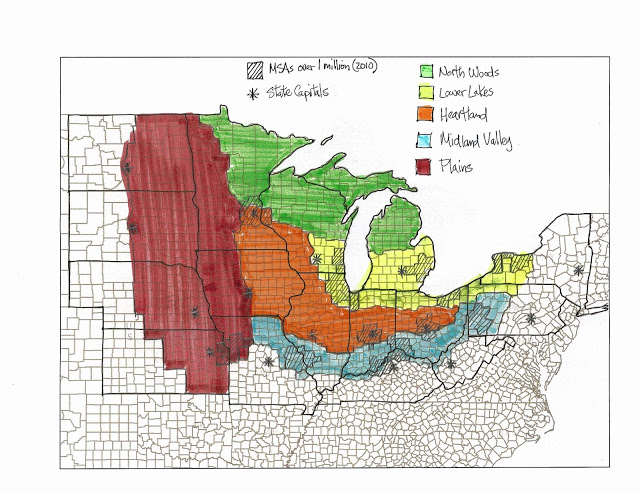

Many of the regions where growth exceeded the national average have historically had low incomes. The former Confederacy accounts for eight of the top 20: Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, Virginia, Texas and North Carolina. (All still lag the national average income of $44,765, though, with the exception of Virginia). The Plains and Intermountain states account for another six (North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Minnesota, Oklahoma). The other big regional winner has been New England, with five of the top 20: New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Massachussetts and Maine. Washington, D.C., ranks 2nd, with growth of 129.4% to a nation-leading $75,329, showing us once again that our rulers treat themselves well.

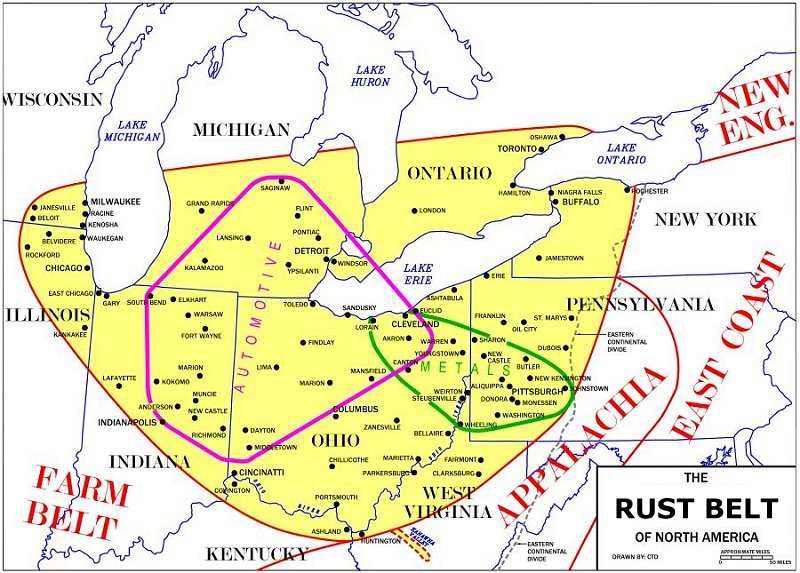

Among the laggards is California, where per capita income grew 62.4%, well below the national average. Several other Sun Belt “boom states” that rank highly on our list of states that have expanded their educated populations the fastest have done poorly in terms of income growth, including, Florida (41st), Arizona (48th), and in last place, Nevada. One complicating factor is that these states have a large proportion of people who earned their income in other, colder parts of the country. Not surprisingly, several of the laggards are in the Rust Belt, including Indiana (40th), Ohio (42nd), and Michigan (47th).

The Future

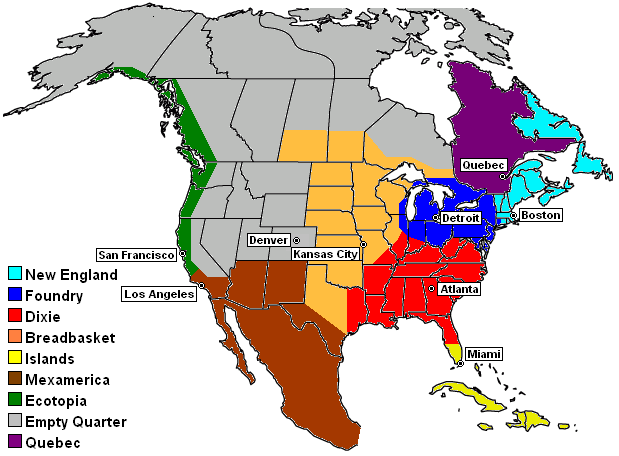

Clearly the economic and educational map of America is changing. There’s a movement of educated people — critical to many industries — to formerly backwater states. Over time jobs, too, are following this path.

In the years ahead we can expect these trends to continue, or even accelerate. There is little reason to believe that states like California or New York are going to re-industrialize or reform their planning systems to help reduce housing prices. They will remain increasingly bifurcated between a very well-educated, affluent population clustered around the most elite industries and an underclass of poor, undereducated people. California, for example, ranks 14th in percentage of college graduates, down from 7th in 1970 but in terms of high school non-graduates it has soared from 44th to 2nd.

This bifurcation doesn’t bode well for these places. People will continue to move to those places where young educated people are now going, notably in the South, the Great Plains, the Intermountain West, and, to some extent, parts of the Pacific Northwest.

Forty years from now America will have many more centers of educational and economic excellence spread across the continent. This may involve a decline in the relative power of some regions, notably California, the Rust Belt and the Middle Atlantic States, but the rise of educated workers and employment elsewhere could help the country retain its competitiveness on an increasingly continental scale.

The Biggest Brain Gain States Since 1970

No. 1: Nevada

Increase In Population Of College Grads, 1970-2013: 1,292%

Pct. Of Adult Population With College Degree, 1970: 10.8%

Pct. Of Adult Population With College Degree, 2013: 22.5%

No. 2: Arizona

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 861%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 12.6%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 27.4%

No. 3: Florida

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 743%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 10.3%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 27.2%

No. 4: Georgia

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 699%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 9.2%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 28.3%

No. 5: North Carolina

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 659%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 8.5%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 28.4%

No. 6: Colorado

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 617%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 14.9%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 37.8%

No. 7: New Hampshire

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 603%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 10.9%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 34.6%

No. 8: Utah

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 585%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 31.3%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 14.0%

No. 9: Idaho

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 563%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 10.0%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 26.2%

No. 10: South Carolina

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 556%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 9.0%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 26.1%

No. 11: Texas

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 555%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 10.9%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 27.5%

No. 12: Alaska

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 544%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 14.1%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 28.0%

No. 13: Virgina

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 517%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 12.3%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 36.1%

No. 14: Washington

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 513%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 12.7%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 32.7%

No. 15: Tennessee

Increase In Population Of College Grads: 495%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 1970: 7.9%

Pct. Of Population With College Degree, 2013: 24.8%

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Photo: 1980s-era Reno, Nevada. Public domain.