This is an excerpt from "Enterprising States: Creating Jobs, Economic Development, and Prosperity in Challenging Times" authored by Praxis Strategy Group and Joel Kotkin. The entire report is available at the National Chamber Foundation website, including highlights of top performing states and profiles of each state’s economic development efforts.

Restoring Growth and Upward Mobility: A Call to the States

Over a year and a half into the recovery, the condition of the American economy is far from satisfactory. For the vast majority of Americans, conditions have improved only marginally since the onset of the Great Recession. Unemployment remains high, job creation meager, and American workforce participation has dropped to near record depths — the lowest rate in a quarter of a century.

Not surprisingly, this spring’s Washington Post-ABC poll revealed that far more Americans feel the economy is getting worse than getting better. There seems to be what the New York Times described as “a darkening mood” among Americans about the future. Confidence in the Federal Reserve’s policies on the money supply has eroded among economists, as few benefits have accrued to smaller businesses and middle-class households.3 Times are particularly tough for entry level workers, including those with educations, and have been worsening since at least the mid-2000s.

This stress is felt keenly by state and local officials, even in areas that aren’t suffering from the highest rates of indebtedness or pension liabilities. Without pension reform, the state of Utah, for example, would have seen its contributions to government workers’ pensions rise by about $420 million a year, an amount equivalent to roughly 10 percent of Utah’s spending from its general and education funds. The states often must deal with declining revenues at a time when the demand for services caused by the recession has increased. And, unlike the federal government, states can neither print their own money nor buy their own bonds.

In the past, states could look to Washington for assistance. Now, whatever the intentions or real achievements of the stimulus package, future increases in federal spending seem likely to be meager at best. The 2010 election effectively ended the nation’s experiment with massive fiscal stimulus from Washington. Indeed, leaders of both parties, President Obama, and perhaps most importantly the capital markets, now acknowledge that deficit reduction will be a priority in the coming years.

This presents a new, and perhaps unprecedented, challenge for the states. With Washington effectively forced to the sidelines, states will now have to address fundamental economic issues relating to growth and employment on their own. Most will have to do so without significantly increasing their own spending.

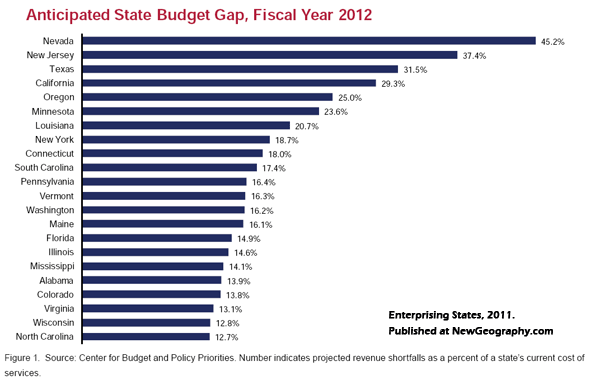

For many states, the short-term prognosis is dire. Altogether, 44 states and the District of Columbia are projecting budget shortfalls for 2012 amounting to $112 billion. The upcoming fiscal year, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, will be “one of the states’ most difficult budget years on record. Retiree benefits for state employees add yet another strain, with the states facing a $1.26 trillion shortfall.”

As a result, states and localities increasingly find themselves forced to impose tough, even draconian cuts in spending. This affects not only newly minted conservative Republicans, but new liberal Democratic governors such as California’s Jerry Brown and New York’s Andrew Cuomo. The only real debate now is how much to rely on taxes and how much on cuts in spending to address the fiscal issues ahead. One casualty: infrastructure spending, which was boosted by the stimulus, now seems to be winding down as well.

This report will try to address the nature of this dilemma and suggest ways to best deal with it. Although we agree with the notion of fiscal probity, ultimately, states can deal with the fundamental problems only by spurring growth and upward mobility. This will not only create new revenues, but also dampen the demand for social services.

A state can neither cut nor tax itself into prosperity. Weak public infrastructure combined with low taxes has failed through history to create strong state economies, as was long the case in the Southeast. But at the same time many large states—California, New York, Illinois—have raised taxes and spending and have suffered a strong out-migration of middle class citizens and jobs for decades.

Now, faced with enormous deficits, there is a temptation to reduce those very “crown jewels,” such as the California public university system, into what University of California President Mark Yudof describes as “tatters.” In trying to balance their budgets, states run the risk of undermining their own long-term recoveries.

The great danger that looms here, in our estimation, is not bankruptcy. Rather, it is long-term stagnation, in which growing demands for social services, combined with weak revenues. foster pressure for more taxes, reduced services or a deadly combination of both. This represents something of a existential problem in a country where the prospect for a better future has long been a hallmark.

The founders of the republic understood the critical importance of maintaining this aspiration, and European observers were struck by the remarkable social mobility in America’s cities. In the 19th century, American factory workers and their offspring had a far better chance of entering the middle or upper classes than their European counterparts. In politics and in daily life, expansion of opportunity was seen as essential to the American experiment. Writing in 1837, one Whig lawyer in Pittsburgh suggested, “If you deny the poor man the means to better his condition . . . you have destroyed republican principles in their very germ.”

Today, this traditional faith is being sorely tested in much of the country. Although both stock prices and corporate profits have rebounded, little has been done that has stimulated employment. Large companies may be sitting on large caches of cash, in part due to low interest rates and a buoyant stock market, but capital remains scarce for the small businesses that create most of America’s new jobs. Indeed, entrepreneurial growth, as the Kauffman Foundation recently found, has now slowed down among most segments of the population.

Of course, there have been remarkable stories of wealth creation and success despite these hard times. But even in Silicon Valley—home to such high-fliers as Google, Apple and Facebook—the overall impact on jobs has been minimal. Of the nation’s 51 largest metropolitan regions, San Jose, the Valley’s heartland, has suffered the largest net loss of jobs over the past decade of any major metropolitan region outside Detroit. The San Francisco area suffered job losses only slightly lower, on a percentage basis, than hard-hit Cleveland.11 Due in part to financial controls, investment in promising new companies has become ever more undemocratic, with the bulk of new money pouring into firms like Facebook coming not from public markets, but from a small, well-heeled cadre of private investors. Venture-backed technology companies, notes Intel co-founder Andy Grove, now find it expensive to “scale” their operations and add employees in California or even the United States. As a result, he suggests, companies tend to indulge in “an undervaluing of manufacturing” that erodes employment. This contrasts with, for example, China, where job creation is considered “the number one objective of state economic policy.”

Much the same can be said of New York, where the paper economy has been boosted by Fed policy but the creation of middle-income jobs continues to lag. New York City’s current financial boom—Wall Street pay hit a new record in 2011—simply reinforces a level of income inequality that is the highest in the nation. Unemployment in the toniest Manhattan precincts reaches barely five percent, while it’s 20 percent in working-class Brooklyn. Not surprisingly, the city’s distribution of wealth is now twice as unequal as in the rest of the nation. It may seem a model recovery on Wall Street, but it is less so on the streets of the nation’s premier city.

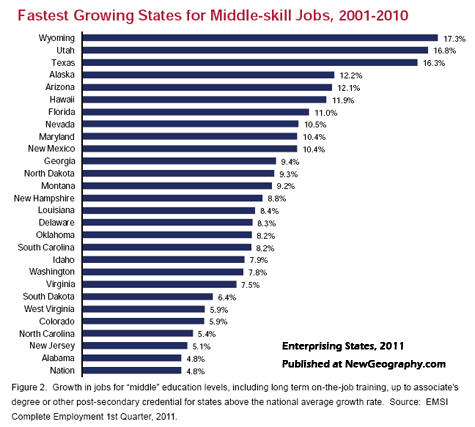

In contrast, the states that have fared best in creating middle-class jobs have been either those close to the expanding federal government, another major beneficiary of the stimulus, or those that have attended to more basic industries, such as energy production, agriculture and manufacturing. These industries have propelled widespread expansions in the Great Plains, parts of the Intermountain West, Alaska and Texas.

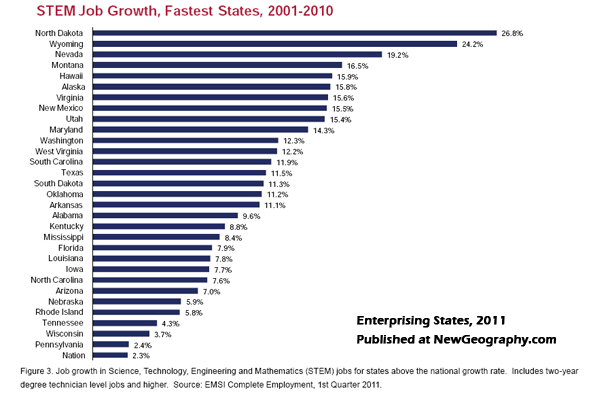

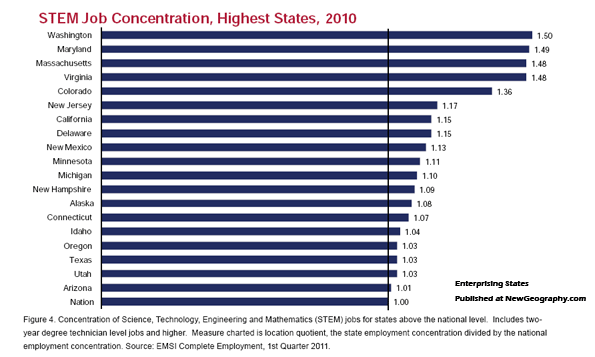

More interestingly, many of these states have also experienced a surge in STEM—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—related employment. In some states, this has come as a result of continuing state investment in education and training; in most cases, these states have simply tended to create a business-friendly atmosphere for companies of all sorts. They have also generally kept housing costs low, something critical to young families.

Perhaps the best way to look at our evolving economy is not so much from the point of view of companies or industries, but of individuals. States often focus on their largest employers, but those companies have been cutting jobs for the past decade. Since 2000, large corporations—which employ roughly one-fifth of American workers— have stopped hiring, as they did in the previous decade, and actually reduced their payrolls by nearly three million while adding 2.4 million jobs abroad.

Andrei Cherny, an Arizona Democrat writing in the journal Democracy, suggests that “both progressives and conservatives have offered little in the way of new answers as their long-held orthodoxies run headlong into new realities.” Cherny admits that the stimulus and the Fed’s strategy of loose money—what he calls “government by hot check”—failed to address the needs of the nation’s large class of small entrepreneurs.

Left out of the equation are the small businesses that, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employ half of all workers and create 65 percent of all new jobs. Most of these firms are small, under-capitalized, and run by single proprietors or families.

In this environment, notes economist Ying Lowery, “Business creation is job creation.” The states that will do best are those that create the conditions to lure and retain those who start companies or who are selfemployed. Policies that target managers of hedge funds, venture firms, or large corporations have their place, but the real action—particularly in a world of ever-changing technology and declining long term employment—lies in the movement of individuals.

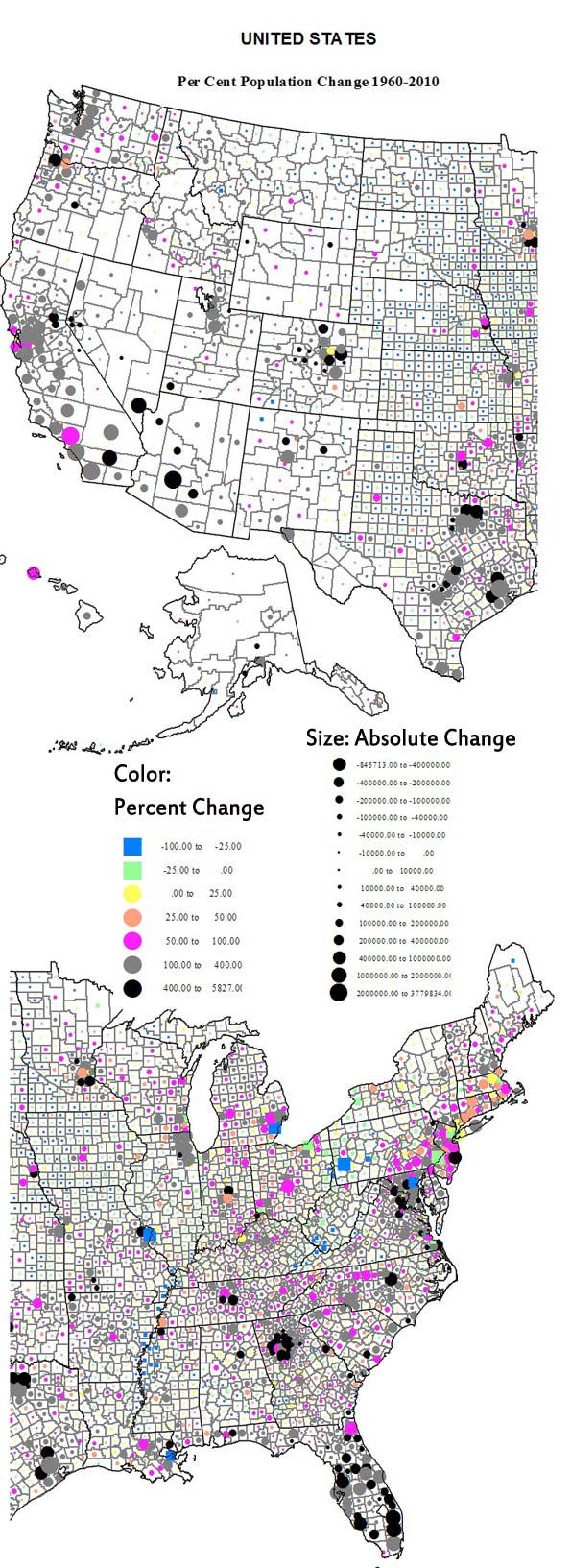

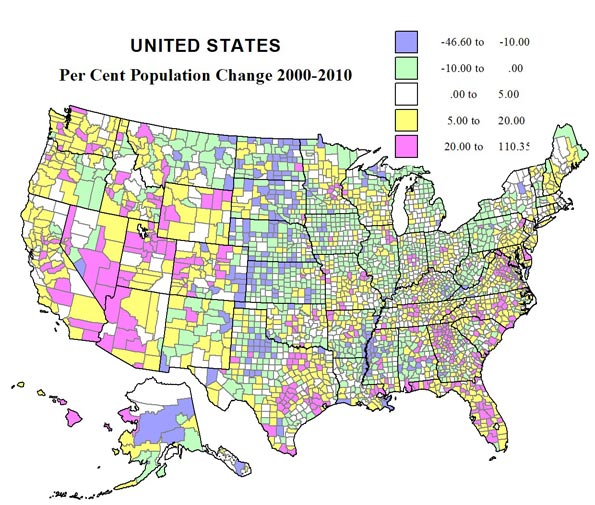

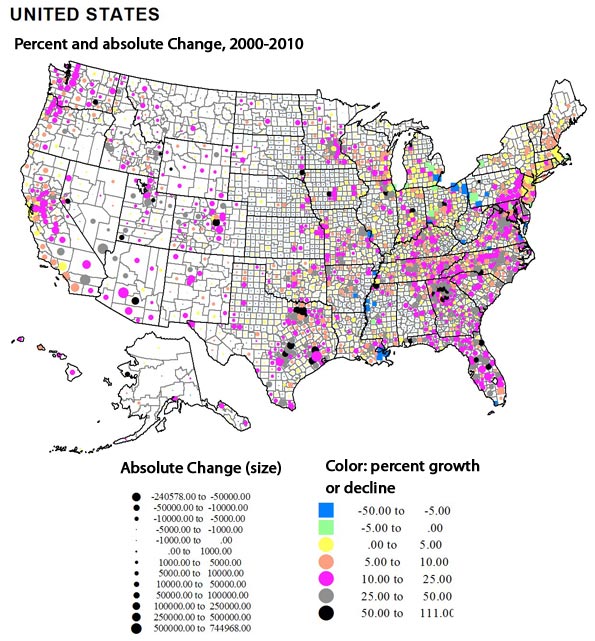

Under these conditions, where individuals migrate or decide to settle will have a critical impact on which states or regions grow. Three dynamic population segments— educated workers, immigrants and downshifting boomers—illustrate the factors that drive their migration patterns. In many ways they represent the “canaries in the coal mine”; where they go is generally where the air is good for entrepreneurship.

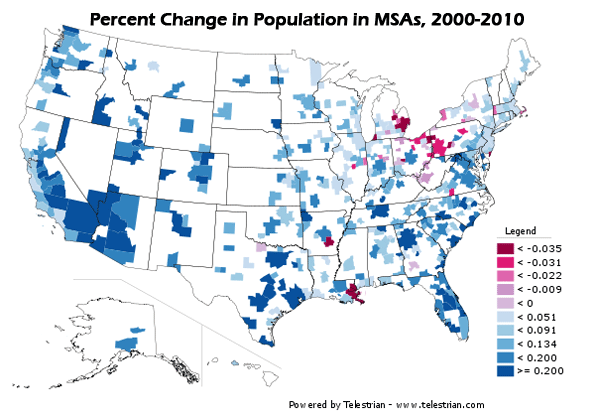

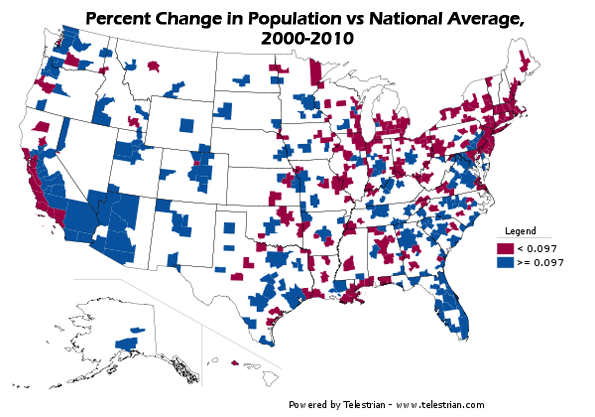

The movement of educated workers has become a much discussed topic among pundits and economic developers in recent years. One common assumption is that “the best” migrants tend to move to “hip and cool” locales, generally on one of the coasts. These workers then form the core of growing industries and, more importantly, new ones. Yet the evidence tells a somewhat different, perhaps surprising, story. An analysis of recent Census data on the migration of educated workers finds that the biggest net growth has taken place not in New York, San Francisco and Boston, but in places like Nashville, Houston, Dallas, Austin, and Kansas City. Indeed, many of the leading “creative class” states, notably California, Massachusetts and New York, fared considerably worse than regions in states such as Missouri, Kansas, Texas and Tennessee in terms of net migration numbers.

These location choices have to do with how individuals make decisions: people move primarily for reasons related to jobs, family, and housing. An analysis of the migration of educated workers, for example, reveals that, for the most part, these workers are moving away from expensive, dense regions to more affordable, generally less dense places. This migration also tends to parallel moves to those states that generally impose fewer regulatory burdens on business.

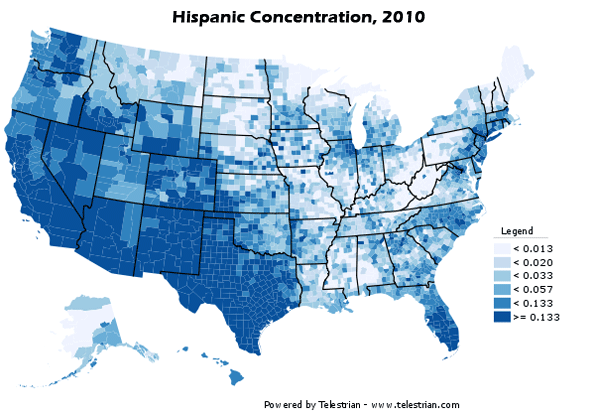

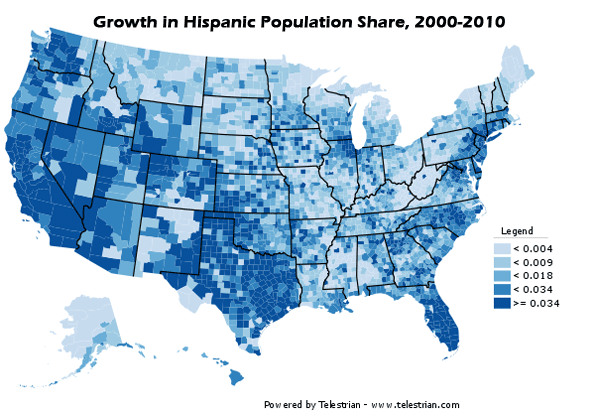

Perhaps even more surprisingly, we see a similar pattern in minority and immigrant entrepreneurship. These groups now constitute a growing percentage of business startups. Overall, according to the Kauffman Foundation, foreignborn immigrants in 2010 constituted nearly 30 percent of all new businesses owners, up from 13.4 percent in 1996. This has also been the one outstanding segment of the population whose entrepreneurship rate has grown throughout the current recession.

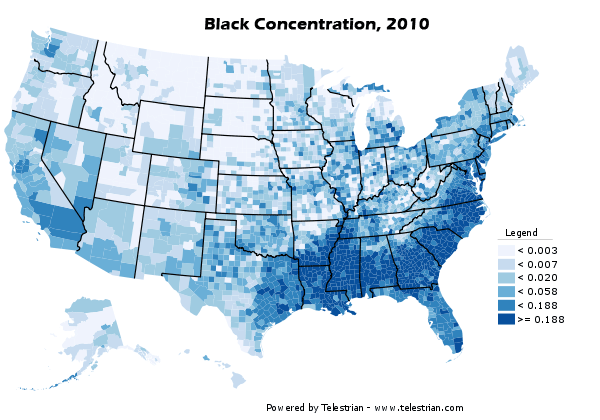

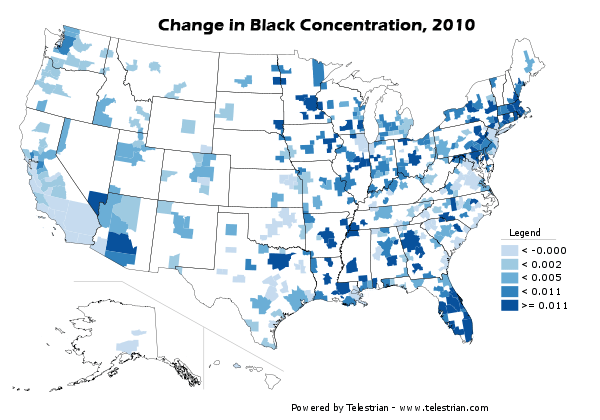

As with the case of educated migrants, minority entrepreneurs tend to establish themselves in less expensive, more business-friendly, and generally less heavily regulated metropolitan regions. A recent survey of minority migration and self employment by Forbes found that the best conditions for non-white entrepreneurs were in metropolitan areas in Georgia (Greater Atlanta), Tennessee (Nashville), Arizona (Phoenix), Oklahoma (Oklahoma City), and several Texas cities (Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and Austin). In contrast, most regions in California and the Northeast, outside of the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area, did quite poorly.

Jonathan Bowles, president of the New York-based Center for an Urban Future, has traced this poor performance to a myriad of factors including sky-high business rents, which stymie would-be entrepreneurs in minority communities. “[Entrepreneurs] face incredible burdens here when they start and try to grow a business,” Bowles suggests. “Many go out of business quickly due to the cost of real estate and things like high electricity costs. It’s an expensive city to do business in without a lot of cash.”

Boomers are unique compared to traditional senior populations. According to the Kauffman Foundation, they tend to be more likely to start businesses than are younger age groups. In 1996, people between 55 and 64 years of age accounted for 14 percent of entrepreneurs; in 2010 they represented 23 percent.

Less is known about the migration of aging boomers, a large segment of the population, but evidence so far suggests that they, too, are moving to such states. According to AARP, most boomers prefer to stay close to where they live—mostly in suburbs—or where their children tend to move, that is, to the low-regulation states of the South and West.

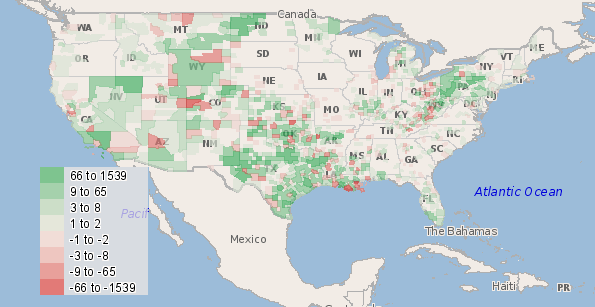

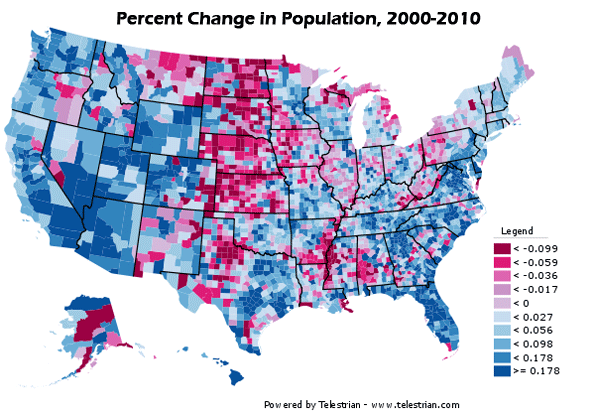

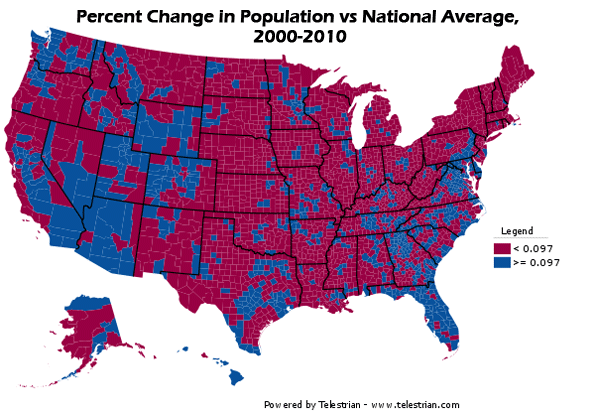

States can draw on these migration patterns in developing their economic policies. Generally, people migrate to states with jobs, and states with population gains generally produce more employment than those with slower growth. Indeed, despite the great disruptions of the mortgage crisis, regions such as Orlando, San Bernardino-Riverside and Las Vegas all recorded double-digit employment gains over the last decade.

More recent developments suggest that future growth may depend on several critical factors. It is clear, for example, that investments in education—for example in Austin, Raleigh-Durham and parts of the Great Plains—have paid off by attracting both individuals and industries, and have made these areas among the healthiest employment markets in the country. Some of these states have suffered less fiscal distress than states elsewhere in the nation, and have benefited from their educational investment through hard times. Investments in community colleges may prove to be particularly essential, since their role in providing skilled workers has been critical in many states.

States that have invested in new infrastructure such as ports, airports, roads and improved transit tend to have a leg up on others that have failed to do so. Even relatively low-tax states such as Texas have invested heavily in recent years in roads and port facilities, which are critical to industries locating there. Even during the recession, many industries—from manufacturing and environmental firms to health care and information technology—have had trouble hiring skilled workers. States are responding by creating job-oriented training programs in states like Ohio, New York, Tennessee, Washington and Wisconsin, which have all established technical institutions separate from community colleges. Tennessee alone has 27 such “technical centers” offering one-year certificates for certain jobs.

Overall, as Delaware Governor Jack Markell has pointed out, businesses generally do not want to eliminate government, but rather want it to be useful for economic growth. Markell, who has done some considerable budgetcutting himself, believes that the focus needs to be on expanding the economy, which will requires improvements not only in schools, but in transportation infrastructure that will make the free market work better.

Perhaps even more important has been creating a favorable business climate. California, for example, possesses the greatest basic economic attributes of any state: a mild climate, location on the Pacific Rim, a world-class university system, and a legacy of strong infrastructure investment. Yet today, despite the presence of leading global industrial zones such as Hollywood and Silicon Valley, as well as the country’s richest agricultural sector, California’s unemployment remains well above the national average and job growth has remained relatively tepid. After many years in denial, even some of the state’s most progressive politicians realize that something is amiss. In a remarkable development, for example, California leaders including Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom recently visited Texas to learn from the large state that has fared best during the long recessionary period. Given the political gap between Californians like Newsom, a former mayor of San Francisco, and Texas Governor Rick Perry, this represents something of a “Nixon in China” moment.

This is not to say that California, or any other state, should draw its economic policy from another state. Those states that attempt to use tax incentives to “lure” industries with no overwhelming need to relocate — as shown in recent findings about Illinois incentives to movie-makers — are often disappointed. In many cases, the incentive game becomes a classic “race to the bottom,” in which the benefits of new jobs often prove transitory. Since the 1990s, just two percent of job growth and decline has been due to businesses relocating across state borders, yet the costly practice of using unfocused tax expenditures to poach companies continues.

Nor can states reliably predict which industries will need more workers over the long term. In the 1990s, economist Michael Mandell predicted that cutting-edge industries like high-tech would create 2.8 million new jobs; in reality, notes a 2010 New America Foundation report, they actually shed 68,000.30 Each state and each region has its own peculiar economic DNA. States with exportable products—for example the Great Plains or the Upper Midwest—may need to focus on ways to get their output efficiently to market. Already affordable, they may also choose to increase their attractiveness to high value-added companies and educated individuals by boosting their education systems and making their metropolitan regions more congenial to well-educated migrants.

In other states such as New York or Massachusetts, the economy is focused on intangible exports like financial services and software. Making themselves more affordable for both individuals and companies may be the best way for states to improve competitiveness. Over the long term, no state economy can sustain its people if it only focuses on the “luxury” sectors; the large number of unemployed and underemployed workers will drain state resources. As those state resources become more limited, decisions about how to structure tax incentives or where to place education and infrastructure investments must be based upon a deep understanding of this economic DNA. Strategic investments will limit wasteful spending and maximize impact in the economic sectors where a state is most likely to grow.

Ultimately, there is only one route to sustainable state economies, and that is through broad-based economic growth. The road to that objective can vary by state, but the fundamental goal needs to be kept in mind if we wish to see a restoration of hope and American optimism about the future.

Read the full report, including highlights of top performing states and profiles of job creation efforts in all 50 states.

Praxis Strategy Group is an economic research, analysis, and strategic planning firm. Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and author of The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050