This is an excerpt from “Enterprising States: Creating Jobs, Economic Development, and Prosperity in Challenging Times” authored by Praxis Strategy Group and Joel Kotkin. The entire report is available at the National Chamber Foundation website, including highlights of top performing states and profiles of each state’s economic development efforts.

Read the full report.

Read part two in this series: The States and Economic Development, Identifying Top Performers

The Jobs Imperative: Power to the States

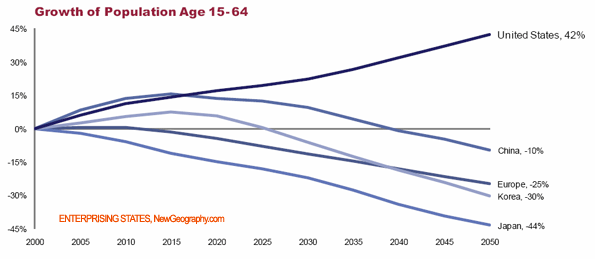

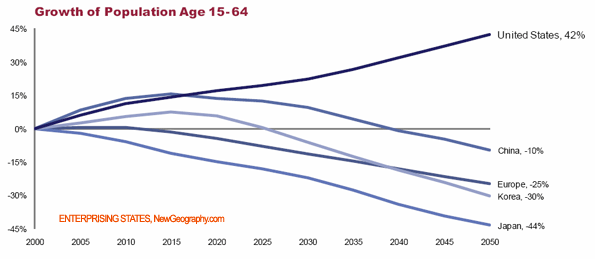

In the coming decades, the United States will enjoy an enormous demographic advantage over its primary competitors in both Europe and East Asia. As countries such as Germany, France, Japan, South Korea and even China will experience declining workforce growth and rapid aging, by 2050 the pool of people aged 14 to 64 in the United States is expected to grow by more than 40%, compared to what it was in 2000. In contrast, China’s workforce will fall by 15%, Europe’s will decline by 25%, and that of Japan will plunge by 44%.

This growth represents an unprecedented opportunity for free enterprise in America, but it also poses a tremendous challenge. What the United States does with its “demographic dividend”—that is, its relatively young working-age population—will largely depend on whether or not the private sector can generate growth in jobs and wealth to help meet the needs of a larger aging population.

Government, too—particularly at the state and local levels—will need to play a role with policies that spur the private sector. Government can facilitate long-term job growth by establishing smart approaches to education, immigration, health care, energy, infrastructure, and tax and regulatory policies.

A University of Kentucky report prepared for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has calculated the total number of new jobs needed “to return the economy to our pre-recession level of employment and provide jobs for all the expected new entrants.” It concluded, “The national total is nearly 23 million workers. Almost forty percent of these additional jobs are concentrated in California, Florida, and Texas, three states that comprise 26 percent of the population as of 2008.” Each of the three states that are predicted to need fewer positions since the start of the recession has fewer than 850,000 people. In these states, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming, the number of workers affected by the recession is more than offset by slower population growth projected by the Census.

And simply to keep pace with population growth in 2010, the New America Foundation estimates, the country needs to add more than 125,000 jobs a month. The employment imperative is particularly critical today, with over fifteen million unemployed. Even if we reach the administration’s goal of providing 95,000 jobs a month this year, 190,000 monthly next year, and 250,000 in 2012, our overall unemployment rate is expected to remain over 8% by 2012. According to estimates by the Economic Policy Institute, it could take until 2013 or even 2014 to get back to the unemployment levels of before the recession.

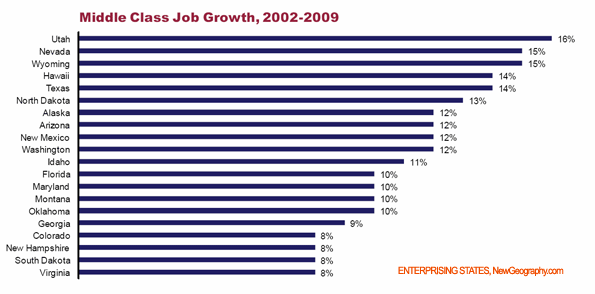

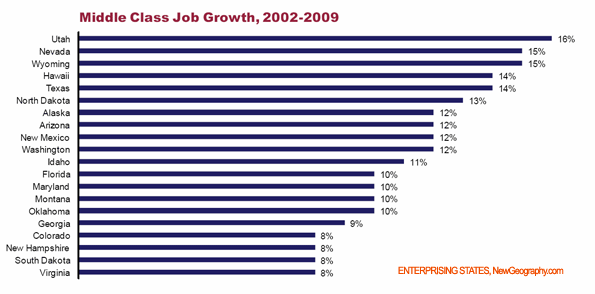

The most critical need is to create jobs for middle and working class people, and for the young, with the teen unemployment rate now over 24% compared to under 15% in 2007.

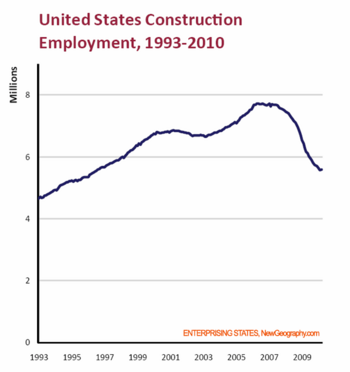

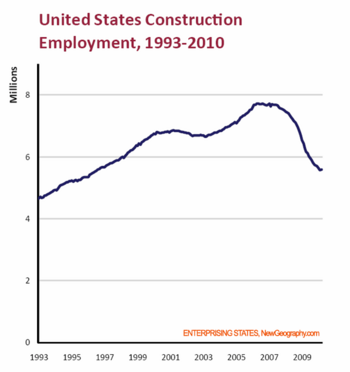

These groups have borne the brunt of the recession—particularly in areas such as construction, where employment has contracted by two million jobs since 2006. The nature of the federal stimulus, which focused more on the social safety net than on infrastructure, appears to have largely missed this heavily male, blue collar segment.

Many have been out of work for a long time. Nearly 6.3 million Americans have been unemployed for over six months, the largest number since the federal government started keeping track in 1948. The average duration of unemployment—28.5 weeks—is the highest since the end of the Second World War. According to the labor department, right now there are roughly 6.1 unemployed people for every job, four times the rate in December 2007.

Needed: An American Approach to Job Creation

More than a year after the passage of the federal stimulus, much more work needs to be done to strengthen of our free enterprise system. Some analysts suggest that we take our lead from the example of European societies, and use tax dollars to stimulate and preserve employment as well as expand social protections. Others argue that adopting European models of shorter hours and more leisure might benefit the economy. Yet these are not rational choices for the United States, since virtually all these societies are aging rapidly, and few have been growing rapidly.

Indeed, many of these societies still have higher rates of youth unemployment than the United States. By the end of 2009, unemployment for those under the age of 25 stood at 21% in the European Union (EU), with some countries—Sweden (27%) and Spain (44%)—at extraordinarily high levels.

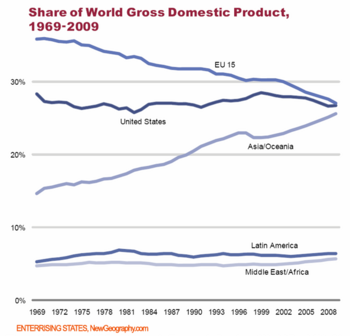

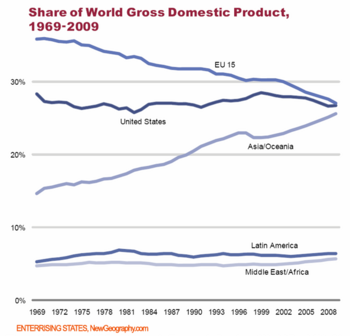

Overall, the core European countries have not grown as quickly as the United States over the past forty years, and seem to be lagging in the current early stages of the recovery. This is a long term trend. The core EU fifteen countries’ share of the world economy has shrunk considerably, while that of the United States has remained remarkably stable. For EU countries, expansive social protection has not been paired with rapid growth.

The United States will need to find its own means to address its unique jobs imperative. Clearly, the expansion and preservation of government employment has proven stimulative, but private sector employment continues to be a struggle in most of America.

One third of the stimulus was directed to local government, and public employment has barely dropped. Even so, there is increasing stress on state and local government, due to the declines in the private sector economy. The limited efficacy of a government-centered approach can be seen in the states—which, after all, cannot print their own money to cover their deficits—with extremely stressed budgets and the inevitability of large cutbacks in public employment.

Another misplaced approach to job creation is the widely embraced notion—both at the federal and the local levels—that government regulations tied to a “green” economy could create a large new employment source. Various studies in countries that have created massive incentives for such employment—Spain, Germany, Denmark—find that the employment-stimulating impact of such policies can be more than off-set by the negative consequences of resulting high energy prices. When cap and trade mandates raise energy taxes and the cost of doing business, they ultimately inhibit job growth. In the long run new jobs in energy sectors will be created by the creation and production of new technologies.

Expanding our production of all energy sources could be a major source of jobs. But the experience in some European countries makes clear that green jobs on their own cannot be a fundamental driver of future job creation. Indeed, literature suggests that much of the job growth in green industries has occurred in China and other countries. To date, the actual impact of green jobs seems to be less than expected.

The one likely way to expand green jobs, notes a series of studies by EMSI, would be through greater economic growth. Most new green jobs depend on the expansion of other key sectors, notably housing, manufacturing, warehousing and agriculture. As these industries expand, they will be the prime markets for new, environmentally responsible technologies and techniques.

The only sustainable way for the United States to create jobs lies in a rapid expansion of the private sector economy, including in the construction, manufacturing, and energy sectors. A ‘green’ economy cannot be created at the expense of the rest of the economy as a whole. Unreasonable constrictions on manufacturing and construction inhibit job growth. And roadblocks to energy development—including to renewable energy projects—from environmental legislation, as well as from environmentalists and NIMBYs, are also harmful to job growth. Improving the quality of the environment should be a primary concern here, of course, as well. But without robust economic growth, the United States simply will have to accept a massive decline in living standards.

The growing divergence between advanced countries should not be viewed as a matter of right or wrong, better or worse. Rather, it signifies how societies of different heritages, faced with different prospects, cope with their evolving futures.

What Is the Best Role for the Federal Government In Job Creation?

The best role for the federal government is to fund national priorities like energy, physical infrastructure, and the national defense, and to set basic health and safety regulatory guidelines that are carefully balanced against the need to maintain low barriers to entry into the market. But, for the most part, the primary mission for economic development went to the states, and, more importantly, the private sector economy.

The mounting federal initiatives to wrest environmental, wage, and benefit concessions from private companies are examples of a centralization of government power over both states and private businesses that could take us in the wrong direction. Although certain times do call for increased federal activity—legitimate threats to national security or economic emergencies, such as the Great Depression or the recent financial crisis—we may be approaching a critical juncture where Washington’s power may be reaching beyond its effectiveness.

The current impulse to create a high-employment economy by imposing federal restrictions—such as the proposal that private firms that do not raise wages will be bullied into doing so by the manipulation of federal contract awards—marks a departure from our free-market traditions. Similarly, possible federal control over local zoning decisions—through such organizations as the EPA—also mark a crossing of the regulatory Rubicon.

States and localities are far better positioned than the federal government to foster strategic investment, regulations, taxes and incentives that encourage private sector prosperity. In large part, this is because they are more responsive to local conditions. Many academic planners, policy gurus, and national media have tended to favor large government units as the best way to regulate and plan for the future. But central planners consistently seek to reduce the influence exercised by the plethora of villages, towns, and cities in the United States: well over 65,000 general-purpose governments. With so many “small towns,” the average local jurisdiction population in the United States is 6,200, small enough that nonprofessional politicians can have a serious impact on local issues.

The American preference for solving problems at the state or local level should be central to the government role in job creation. One size determined in Washington will not fit all. South Dakotans and Californians will prefer to address employment problems in different ways. Within the limits of constitutional rights, we should let them try their hand, and let everyone else learn from their success or improve upon their policies.

Indeed, many Americans on both the right and left are instinctive decentralists. Our economic evolution mirrors this trend. America’s entrepreneurial urge, in contrast to developments elsewhere, has actually strengthened. In 2008, 28% of Americans said they had considered starting a business—more than twice the rate for French or Germans. Self-employment, particularly among younger workers, has been growing at twice the rate of the mid-1990s.

For this reason, supporting new businesses—and small and medium-sized firms—by ensuring that they can get the credit they need is an essential piece of the job-creation picture. For jobs to grow, these businesses must thrive.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship Are the Key to Solving the Jobs Imperative

America will depend on its emerging population of younger workers to keep expanding its economy. In the 1970s, when the coming-of-age of the boomers began to impact the labor market, labor force growth created a period of higher unemployment. Now, we could see a reoccurrence as the large millennial generation starts to seek employment. Yet now, as then, predictions of a long term labor glut could well change as these workers find and develop new opportunities.

This happened to the boomers in the late 1980s, when talk of long-term high unemployment was replaced with concerns over a labor shortage. The growth of new industries tied to the use of computers, and later of the internet, created a surge in demand for skilled workers. As boomers integrated into the workforce and were replaced by less numerous generation “X”-ers at the entry level, companies fretted increasingly about a diminishing pool of workers.

The opportunities for employment created by the rise of new industries, and by the innovative expansion of established businesses, cannot be underestimated. Such innovation has long been the source of new growth for the American economy, although the exact nature of that innovation is impossible to predict. Much of the pioneering will likely come from skilled immigrants, who are

estimated to have started a quarter of all venture-backed

public companies between 1990 and 2005.

This enterprising spirit reflects a broad, long-term American trend. U.S. employment has been shifting not to mega corporations, but to individuals and smaller units; between 1980 and 2000, the number of self-employed individuals expanded tenfold to comprise 16 percent of the workforce.

The smallest businesses—the so-called microenterprises— have enjoyed the fastest rate of growth. By 2006 there were some twenty million such businesses, one for everysix private-sector worker. Hard economic times could slow this trend, but historically, recessions have served as incubators of innovation and entrepreneurship. Many of the individuals starting new firms will be those who have recently voluntarily left or been laid off by bigger companies.

The Vital Role of Infrastructure and Basic Industries

To succeed in the mid-21st century, Americans also will need to pay more attention to the country’s basic industries. Some assume that the American future can be built around high-end “creative” jobs, without ever reviving the industrial economy or rebuilding our physical infrastructure. In the America envisioned by advocates of “the creative economy,” our productive facilities would serve mainly as tourist attractions, much as we now visit restored pioneer villages.

Such an approach assumes that our rising competitors, notably China and India, will surrender high value activities such as media, finance and engineering. This is a dangerous and historically ill-considered assumption. In the 1980s, Japanese firms that were widely written off as “copycats” became primary innovators, particularly in automobiles, semiconductors, and computer games. In the coming decades, Chinese, Indian, and Brazilian companies—to name a few—will seek to move from low-wage work to more specialized, innovative kinds of products. The enormous revenues generated from the less trumpeted activities will provide the funds to invest in their move into ever higher-end activities.

Americans can create a more prosperous future, but only if we focus on maintaining the physical infrastructure necessary for basic production and transportation, as well as on developing the intellectual prowess of our citizenry. America’s unique demographics require the country to pay attention not only to high-tech industries or financial services, but also to the basics: construction, manufacturing, agriculture, and energy.

These critical industries underpin our prosperity and employ our expanding blue-collar workforce. They can provide new opportunities for the majority of workers who do not possess four year or advanced college degrees. In 2005, the National Association of Manufacturers, the Manufacturing Institute, and Deloitte Consulting surveyed eight hundred U.S. manufacturing firms: More than 80% reported that they were “experiencing a shortage of qualified workers overall.” Nine in ten firms stated that they faced a “moderate-to-severe shortfall” of qualified technicians. By 2020 this shortage could grow to 13 million workers. A resurgent manufacturing sector would also boost the country’s technological workforce. By 2007, industry employed about a quarter of the nation’s scientists and related technicians.

This revived focus on production would help large swaths of the country. The Great Plains area, which is still profiting from industrial and agricultural expansion, would benefit, as would the Great Lakes, which has weathered so many challenges in recent decades. Historically neglected regions such as Appalachia would also profit.

The Critical Role of States

America is a vast country made up of hundreds of diverse economies. From early on, very different industries clustered in different places. There has been wide divergence in the skills and abilities of local populations. Although federal intervention is necessary in certain areas—for example, in creating national research institutions or interstate transportation—it is often at the state or local level that the best policies for a particular region can be developed.

The need to tailor economic development to local needs has been a critical aspect of the success of our federal system. By giving a state wide leeway to develop its own solutions to the jobs imperative, we would be providing the other states with potential role models—as well as a warning system of policies to avoid—in their own strategies. The states are described in the famous opinion issued by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis as places that “serve as a laboratory” where the nation can “try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

States have often been leaders in fashioning progressive approaches to economic development. Private and state-sponsored development created the initial network of roads, canals, and steamboats that knit together regional economies. When President James Madison vetoed federal funding for the Erie Canal in 1817, the New York legislature used its own tax and credit resources to complete the 363 mile system eight years later. Eventually the canal helped assure the Empire State’s national preeminence. Other states, including Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Maryland and Virginia, followed suit with their own canal-building projects.

In the 1920s and 1930s states—and some municipalities—also invested heavily in wealth-creating infrastructure, including highways and water and power systems. These investments supplemented significant new underwriting of projects from private corporations. States continued to make these investments throughout the 1950s.

At the time, no state was more successful at developing its economy than California. Under both Republican and Democratic Governors, California developed what has become a widely accepted model of local economic development based on the expansion of traditional infrastructure—roads, bridges, water and energy systems—matched by massive investments in “human capital”, including a master plan for higher education that spanned the elite universities to the community colleges.

California’s state investment and business promotion policies inspired other states, notably Texas and North Carolina. This state role was also embraced by the young Governor of Arkansas, Bill Clinton. Faced with the issues of a poor, racially divided state, Clinton recognized that, given the deep divisions in Washington, “There is no alternative to continued intense state efforts to deal with our most pressing domestic problems.”

Although unemployment dropped, there remained problems relating to national competitiveness and declining middle class wages, Clinton argued. But he continued to believe in the exercise of local power. “In a country as complex and diverse as ours, in which most job growth is generated by small business,” he noted, “many of these [economic] issues will almost have to be dealt with at the state level.”

In David Osborne’s landmark work, Laboratories of Democracy, he described how the late 1980s and early 1990s saw the emergence of a whole host of innovative Governors. The “first agenda” of these Governors, Osborne noted, was “creating economic growth”, a notion Governor Clinton later used effectively in his campaign for the Presidency.

In today’s federal-level climate, states could potentially play a more significant role than they did in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Chuck McCutcheon, co-editor of Politics in America at CQ-Roll Call Group, suggests that continued DC “political gridlock” makes the states better suited to deal with major policy issues. At the state and local levels, he suggests, politicians are more likely than their highly polarized federal counterparts to “get along” with each other.

Conclusion: The Power of the States to Lead the Jobs Imperative

Ultimately, states and localities are best qualified to meet the jobs imperative. As Alexis De Tocqueville observed, it is natural that citizens of a state or locality are more solicitous about “the increasing prosperity of his own district,” and this serves “to stir men more readily than the general interests of the country and the glory of the nation.”

As our country grows, reaching 400 million people by 2050, the differences between our various states and communities will grow. We will have more diverse regional economies, demographics and cultures. We need to look at these local sources—what Thomas Jefferson called “our little Republics”—to lead the jobs imperative. It is an imperative upon which depends the future success of our entire nation.

Read the full report.

Praxis Strategy Group is an economic development, analysis, and strategic planning firm. Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and author of The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050