A pending bill in Congress to reduce carbon emissions via a “cap and trade” regime would have significant distorting effects on America’s regional economies. This is because the cost of compliance varies widely from region to region and metro to metro. This is all the more important since such legislation may do very little to reduce overall carbon emission according to two of the EPA’s own San Francisco lawyers.

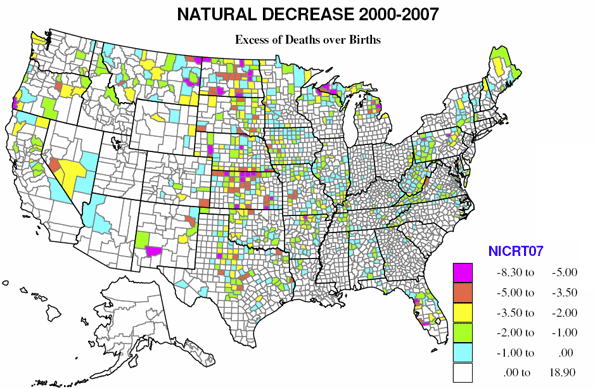

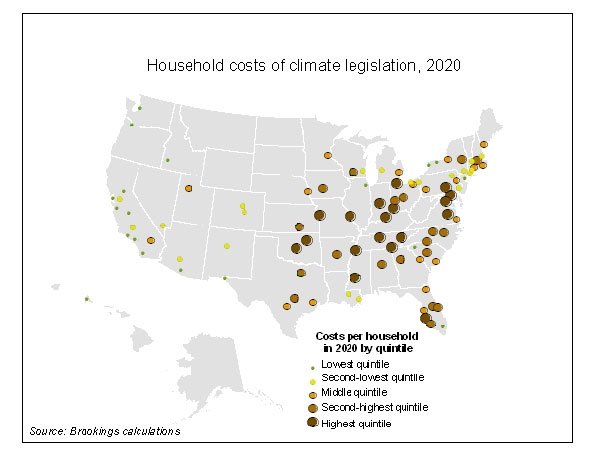

The Brookings Institution recently calculated the projected cost of compliance under the cap and trade plan on a metro by metro basis and produced the map below for The New Republic:

The costs of compliance are highest in the lower Midwest through to the Mid-Atlantic and in the South. New England, the Upper Midwest, and the West are the winners from a cost standpoint.

The actual costs vary from a high of $277 per household per year in 2020 in Lexington, KY to a low of $96 in Los Angeles among the 100 largest metros. Other hard hit metros include Washington, DC ($250), Indianapolis ($246) and Kansas City ($228). Among the winners are Portland ($107), San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont ($119) and Chicago ($135).

In aggregate, this adds up to a significant amount of money. The Cincinnati metro had 815,000 households in 2008. Brookings did not include their household estimates for 2020, but even with no population growth at all, at $244 per household that still adds up to about $200 million per year in compliance costs. To put that in perspective, Cincinnati is proposing to construct a new downtown streetcar system for that same amount of money. It could conceivably build a new streetcar line every single year in perpetuity for the cost of compliance. Portland has 835,000 households, for an annual compliance cost of $90 million. Though they are about the same size regions, Cincinnati will be paying over $100 million more per year compliance costs. This creates a $100 million disincentive to live or locate a business in Cincinnati vs. Portland.

In short, cap and trade creates disparities between metros. As the New Republic put it, “place matters” on cap and trade. And because the effects are geographically clustered, these disparities aren’t just local, they are regional. This is enough to immediately prompt the question as to whether or not this was an implicit design goal of the system.

Among the biggest beneficiaries of cap and trade is California. Its large metros are clustered together at the bottom of the list. I noted previously how California is placing a huge bet on the green economy as its engine of economy renewal. In fact, beyond legacy industries such as high tech, agriculture, and entertainment, California’s political leaders are betting their entire future on green. With so much on the line for California, it should come as no surprise that the state would seek to federalize its policies and institutionalize the advantages it has in this arena through its state level climate regulations. One might even better name this bill “The California Economic Recovery and Competitor Hobbling Act of 2009”.

This reality isn’t lost on Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels. With Indianapolis the fifth hardest hit metro in the country, it is no surprise he denounced the plan in a Wall Street Journal editorial, saying, “Quite simply, it looks like imperialism. This bill would impose enormous taxes and restrictions on free commerce by wealthy but faltering powers – California, Massachusetts and New York – seeking to exploit politically weaker colonies in order to prop up their own decaying economies.”

It is clear that getting a bill out of Washington is not just a matter of cost, but of states and regions jockeying for position. The significant regional disparities in impact grind the legislative gears and might ultimately imperil getting legislation passed. Reducing regional disparities could help improve the chances of action on carbon.

But shouldn’t places that implemented what is considered good policy be rewarded? To some extent, yes. Many places actually voted to cause economic pain for themselves for the sake of a better environment. Other places have fought environmental regulation every step of the way. Clearly, we do want to provide incentives for good behavior, and certainly not reward bad.

On the other hand, not all the differences in current carbon emissions or abilities to reduce them are the result of good policy. Quite a bit of them are the result of simple good luck. Some places have climates that reduce the need for heating and air conditioning. Other places face more extreme weather.

Plentiful clean energy sources are unequally spread throughout the country. Not every place has access to large amounts of solar, wind, or hydro power sources. Much of the Midwest and South built coal fired power plants due to plentiful coal supplies in the region. Technology and transportation costs made other sources cost prohibitive. Carbon emissions were not on anyone’s radar then. Some places like Chicago were fortunate to build nuclear plants, which were bitterly opposed by environmentalists at the time, but now are praised by some as a source of low carbon power.

In short, much of the inequality in carbon emissions results from accidents of geography or history, not deliberate bad choices. People shouldn’t be punished for practices that were rational at the times. As Saul Alinksy put it, “Judgment must be made in the context of the times in which the action occurred and not from any other chronological vantage point.” And while one could say perhaps regions whose climates require excessive heating and cooling shouldn’t be favored places to live, one could say the same about much of the West, including California, whose existence depends on a vast edifice of what many consider environmentally destructive water works.

To actually get action on carbon – the true imperative – we should adopt the following policy guiding principles:

- The goal is carbon reduction, full stop. Encumbering it with additional regional economic gamesmanship, or becoming overly enamored with particular means to that end should be avoided.

- Reducing carbon emissions will come with an economic cost. It isn’t realistic to expect that we will get away with pain free reductions. Obviously we should seek to get the best blend of costs and benefits, but let’s not pretend we can have our cake and eat it too, holding carbon action hostage to a standard that can never be met.

- The carbon reduction regime should not create significant regional cost disparities. As a purely practical matter, this helps ease passage and should be embraced. Complete equality is never realistic, but when some regions will pay twice as much as others, that by itself creates oppositional voting blocs. If a cap and trade scheme is the preferred approach, then perhaps assistance to high compliance cost areas should partially fund the transition away from coal and towards less polluting sources.

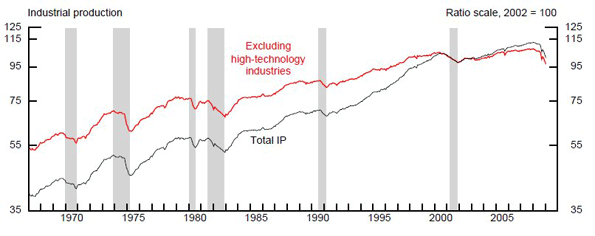

- The carbon reduction regime should not encourage business to migrate offshore. We should also not take action that reduces the attractiveness of America as a place to do business and especially to manufacture. Regulatory arbitrage already provides an incentive to move to China, where you can largely escape environmental rules, health and safety regulations, and avoid the presence of independent, vigorous unions. An ill chosen carbon regime could simply enhance China’s allure as a “carbon haven”. Again, this skews manufacturing regions and labor interests against action on carbon, while shifting production to areas with only minimal regulatory restraints.

In short, action on carbon reduction may well be a good policy goal. But we shouldn’t embrace any means to that end uncritically if it creates huge distortions in regional economic advantage or further damages America’s industrial competitiveness.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.