A decade ago, the path to a successful future seemed sure. Secure a foothold in the emerging information economy, and your city or region was destined to boom.

That belief, as it turned out, was misguided.

In the decade between 1997 and 2007, the information sector–which includes jobs in fields from media, publishing and broadcasting to computer programming, data processing, telecommunications and Internet publishing–has barely created a single new net job, while some 16,000,000 were created in other fields.

The biggest losses have been in the telecommunications sub-field, which has shed 400,000 jobs nationwide since its peak in 2000. Not surprisingly the media and publishing industries have also lost ground, while employment in other arenas such as motion pictures, software and data-processing have remained stagnant for much of the decade.

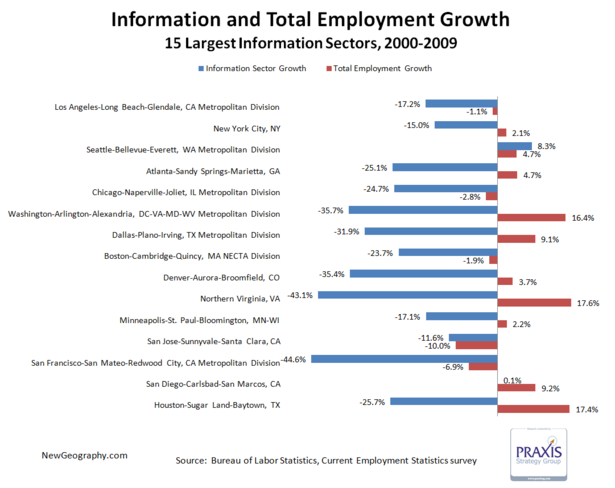

Equally critical, it seems clear that simply being a high-tech magnet does not make a region a prodigious job creator. The San Jose metropolitan area, better known as the heart of Silicon Valley, boasted over 960,000 jobs in 1997. Last year, even after the ballyhooed Version 2.0 of the dot-com boom, that number had actually declined–to barely 900,000. According to figures from economic-strategy firm Praxis Strategy Group, other traditionally tech-heavy areas, including San Francisco and Boston, also did poorly in terms of growth through the balance of this decade.

Perhaps most disturbing, many areas are also losing their share of the information industry. For example, the information-sector job count, notes the Public Policy Institute of New York, has actually been stagnant or in decline in places like New Jersey, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota and New York.

The same pattern also affects so-called “cool” cities that were supposed to be ideal for high-tech jobs, according to a recent study by my colleagues at Praxis. The biggest declines in information jobs since 2000 have occurred in San Francisco (which lost 31,800 jobs), Northern Virginia (35,200) and Washington, D.C. (40,700).

Silicon Valley dropped 5,400 positions since 2000, which amounts to 11.6% of all its information-sector jobs. The only bright spot for blue states is in Washington, where growth is driven by big employers

Faced with all these cities that are merely struggling not to lose any jobs, just where is the tech-sector growth? It’s in less-celebrated areas of the country, like Idaho, New Mexico, North Carolina, Nevada–and in parts of Florida, South Dakota and South Carolina. By region, the fastest gainers turned out to be places like Orlando, Fla. (with 2,176 new information jobs since 2000), Madison, Wis. (2,400), Boise, Idaho (1,500), Wilmington, N.C. (1,267) and Charleston, S.C. (1,033).

What distinguish most of these places are factors beyond prominent employers. These could include such prosaic things as tax rates (particularly on incomes), the cost of housing and the overall climate toward business. Information-sector jobs, it turns out, follow the basic rules of economic development seen in other industries.

Of course, this is not to say tech jobs don’t matter. As the Milken Institute’s Ross DeVol argues in his new study of high-tech centers, technology jobs pay better than most, and their presence can boost other parts of local economies. And although they may not be multiplying fast, in some centers, like Silicon Valley, Boston and Southern California, whatever employment already exists has enough inertia to allow them to remain the largest tech centers in the country.

Yet the problem is that the information economy, by itself, simply doesn’t reliably spur broader economic growth. That may be due to changes within the sector itself. From the 1980s to the mid-1990s, tech firms largely focused on creating productivity-enhancing products. Many of them also used on-shore manufacturing. Aerospace was a smaller industry, but it was still vital.

These catalysts helped create dynamic companies that both employed large numbers of people directly and used contractors (whose numbers increased). The Silicon Valley I reported on in the mid-1980s housed an essentially industrial economy with many good jobs for middle- and working-class people. It was both a hotbed for pioneering entrepreneurs and a society that offered and encouraged opportunity.

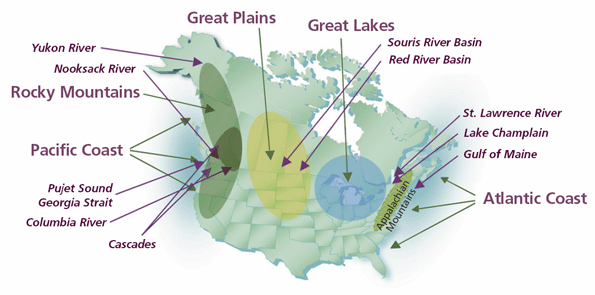

Today, however, tech has become increasingly software- and media-oriented. New companies tend to emerge from a small pool, and they are financed by a relative handful of local venture capitalists. Once launched, they may conduct some research and development at home, but marketing and customer service are either off-shored or moved to remote locations like the Great Plains or the “Intermountain West,” between the Cascades and the Rockies.

As a result, even star companies like

This, of course, represents very good news for a select few: investors and a handful of highly educated software engineers. But the Bay region’s broader economy and society isn’t as lucky.

That’s because most segments of the information sector that do create lots of jobs tend to take place elsewhere. For example, when Intel considers opening a new chip plant, which could open up 7,000 new positions, it won’t build it in the Valley of its birth but rather in farther-flung locales like Oregon, Arizona and New Mexico. California has become too expensive; businesses there are heavily regulated and taxed for most industrial activity.

So maybe it’s time to unlearn some of the assumptions we developed during the first tech boom. In the 1990s and early 2000s, many held that the information revolution would tame the business cycle, guarantee constant high returns and create widespread prosperity. Now we know better.

The model of Silicon Valley, as DeVol suggests, cannot be easily duplicated. Another well-promoted formula, linking great universities to up-and-coming hip cities for the so-called “creative class,” has proved very limited when it comes to creating new jobs. And, anyway, trends in tech growth suggest that basic economic conditions like general affordability, taxes and the regulatory environment play an important role.

Just as troubling may be the class divisions on display in places like Silicon Valley. As manufacturing and middle management jobs have fled, its capital, San Jose, has become more of a backwater. As local blogger Adam Mayer has pointed out, San Jose increasingly serves as a dormitory for the bottom-feeders of the Silicon Valley food chain.

In contrast, tech power and influence is shifting to those areas that have always been well-to-do and are likely to stay that way–academically-oriented places like Cambridge, Palo Alto and San Francisco. They are becoming ever-more-exclusive reserves for the restless young and those with the greatest talent within the media and software industries. Meanwhile, the service class commutes in from the surrounding periphery to tidy up and run restaurants, while high housing costs and an overall lack of opportunities for other kinds of workers drive away much of the middle class, particularly families.

In geographic terms, the real losers in this brave new tech world may be the communities on the fringes of those high-end tech areas. Take Lowell, Mass. Lowell, a former mill town widely celebrated for its tech-led revival in the 1980s, has seen little job growth since the late 1990s. But why pick Lowell, when it’s far cheaper and easier to expand in Boise or, even better, Bangalore, India?

The time has come to let go of vintage fantasies about tech that date from the 1990s. Key regions–and the country as a whole–need to understand that the information sector is best seen not as an end in itself but as an industry that derives its value from how it works with other parts of the economy, such as finance and business services, agriculture, energy, manufacturing, warehousing and engineering. (Manufacturing alone employs 25% of the U.S.’s scientists and 40% of its engineers–and their related technicians.) We have to nurture a broad industrial base so that innovations in this sector do not simply end up boosting off-shore industry.

Techies won’t save us from the folly of deindustrialization; in essence, we can no longer believe that it’s possible to Google our way to prosperity.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History and is finishing a book on the American future.