The Midwest’s troubles are well-known. The decline of manufacturing has resulted in job losses and dying industrial towns. The best and brightest have fled the flatlands for more exciting, sunnier, mountainous, or coastal places where the real action is. Even Peyton Manning has left the heartland for the Rockies.

This narrative is so deeply embedded both in and outside of the Midwest that many people overlook the ways in which parts of the region are bouncing back. The Midwest’s story is important because it serves in significant ways as a regional microcosm of how growth and opportunity should look in America today.

In a recent study we look at trends that upend the conventional wisdom about the Midwest. We find that it is neither doomed to a slow and dirty demise like an old house on an eroding slope, nor forced to reinvent itself Dubai-style in order to compete with Silicon Valley or Manhattan. The Midwest’s future is rooted very much in its past—but with some important updates.

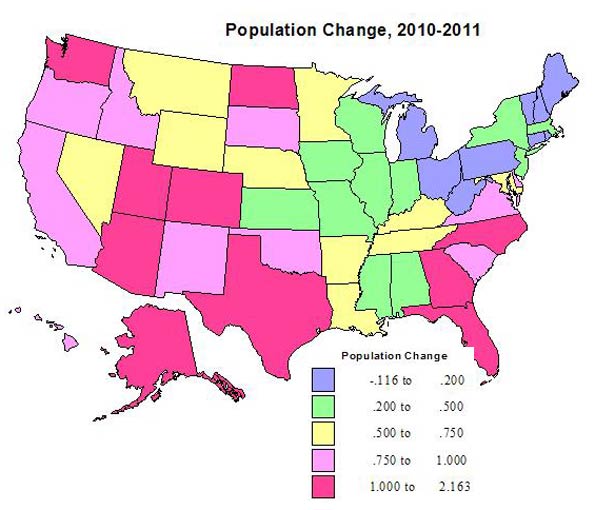

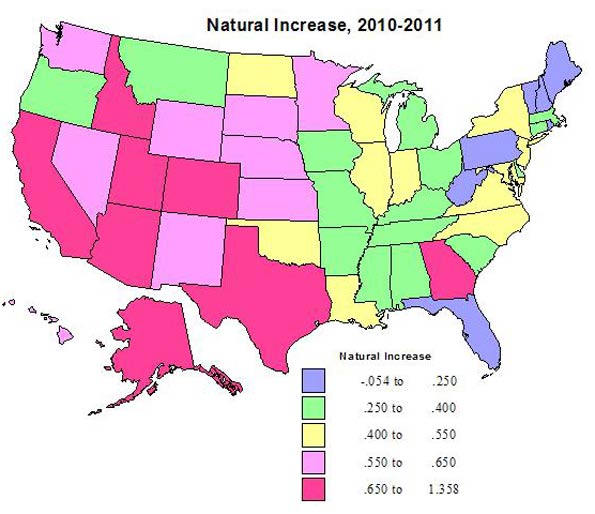

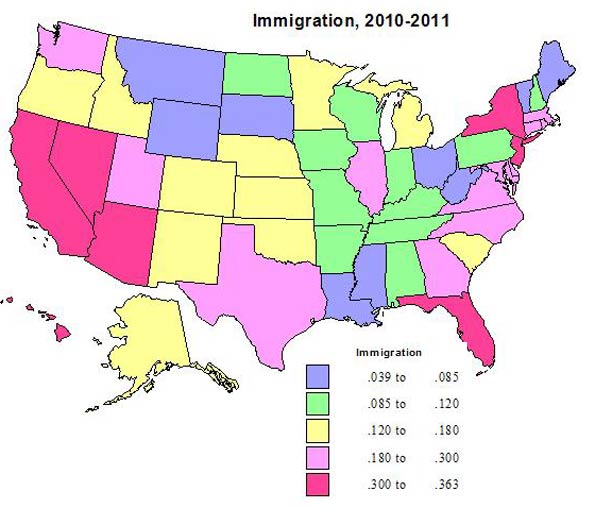

What do we mean? For starters, this means capitalizing on Americans’ desire to reside where the cost of living and doing business is favorable. As the last Census showed, Americans move in droves to regions where the cost of living is low, businesses face fewer obstacles, and workers have choices. As Wendell Cox and Joel Kotkin have shown, this goes for 25- to 35-year-olds as well as 55- to 65-year-olds. People want options and a good quality of life at a price they can afford.

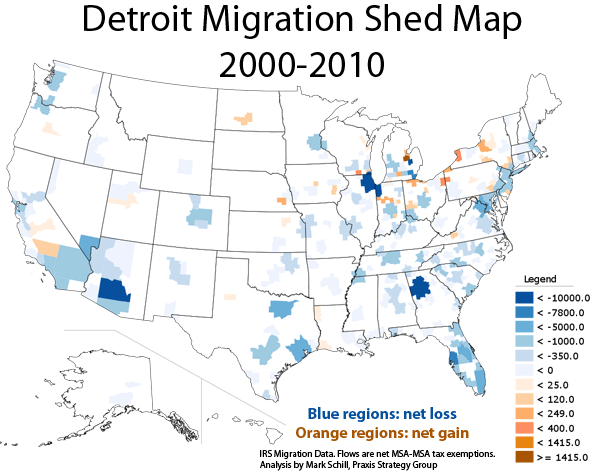

In the Midwest, these trends have favored placed like Columbus, Ohio, and Indianapolis, Indiana. When people hear “Midwest,” they are more likely to think of this kind of picture:

The blue areas show destinations to which people from Detroit have moved between 2000 and 2010. The brown shades are the areas from which Detroit has drawn people. Given Detroit’s well-publicized decline, all the blue should be no surprise.

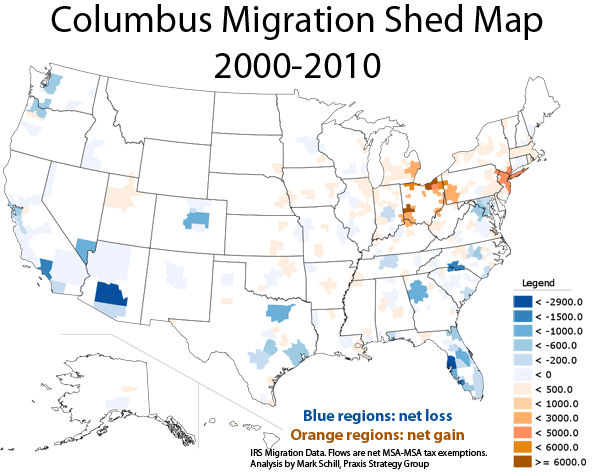

But a respectable portion of the Midwest looks like this:

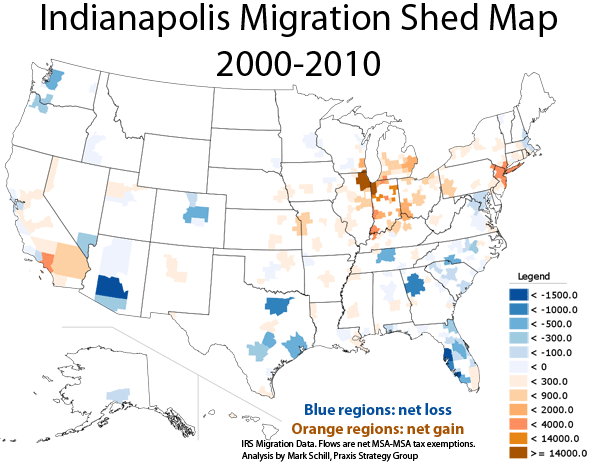

And this:

Like most parts of America, Columbus and Indianapolis have seen a net outmigration southward to Florida and Texas. No surprise there. But note how both cities are stealing population from Chicago, Detroit, New York, and even southern California and Miami in Indianapolis’s case. The maps also show how intense interstate competition within the Midwest is right now.

One important measure of the cost of living is housing affordability, which is typically set at 3.0 as a measure of median housing price divided by median income. Compared to San Francisco at 7.2, New York at 6.1, Los Angeles at 5.9, and Miami at 4.7, Columbus stands at 2.8 and Indianapolis at 2.4. Charlotte, which has been an exemplary Sun Belt growth magnet for a while, stands at 3.9, a slight click above the Chicago area’s 3.8.

Affordability and overall quality of life as measured by schools and greater disposable income matter a lot—even to technology entrepreneurs. Some Midwestern areas are outpacing coastal areas on this front. In a recent Forbes ranking of tech growth in the nation’s largest 51 metro areas, the Midwest had three cities within the top 15, with Columbus in third position, followed by Indianapolis and St. Louis.

But it would be wrong for tech boosters to think the Midwest’s future rests in harnessing the power of this sector alone. Rather, it’s a combination of brains and brawn that signify the Midwest’s core strength. When we look at Midwestern areas that have experienced above-average growth in bachelor’s degrees, there are important overlaps with areas experiencing above-average growth in manufacturing, too.

In the corridor from Madison to Milwaukee, or the outlying areas around Chicago, or the Indianapolis metro area, or even in the Quad Cities on the Iowa-Illinois border, we see higher educational attainment and manufacturing growth occurring together. Cedar Rapids, Iowa, had the highest GDP growth from 2000 to 2010 of any metro area in the Midwest. A new corridor has grown up between Cedar Rapids and Iowa City, home to the University of Iowa; it takes advantage of the region’s historical manufacturing capacity and blends it with new technology. Peoria, Illinois, is second to Cedar Rapids in GDP growth. Peoria is home to 200 manufacturing firms, and it is also a Midwestern leader in college degree attainment.

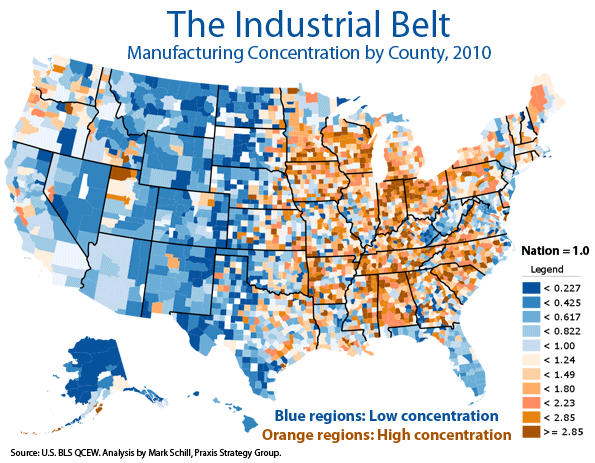

Manufacturing continues to be part of the regional DNA in the Midwest. Trying to move away from it would be a fool’s errand, as this picture shows:

The concentration of manufacturing in middle America is a real asset, especially when combined with higher levels of educational attainment, as we have seen. The Midwest is still home to much of the nation’s skilled labor force. And contrary to the declinist narrative mentioned at the outset, the region has added 50,000 “heavy metal” manufacturing jobs since 2009.

The challenge for the region, actually, will perhaps be filling manufacturing jobs rather than creating them. A recent Deloitte survey found that 83 percent of manufacturers nationwide suffered a moderate or severe shortage of skilled production workers. The Midwest is poised to establish what we call a “new industrial paradigm,” characterized by a blend of heavy manufacturing, new technology, a more highly educated industrial labor base, and lighter labor restrictions (Indiana just became a right-to-work state, and the much-publicized debates in Wisconsin and Ohio over labor laws have only served to draw more attention to the need for reform, whatever the near-term effects). When you add to all of this the new energy sources discovered in some parts of the Midwest—such as new finds in Utica shale in Ohio—a new industrial paradigm in the region could end up being a large source of new wealth creation in the coming generation.

So why might the Midwest be something of a microcosm for how growth and opportunity look in America as a whole, given its idiosyncratic reliance on manufacturing not shared by other regions? The main reason is that middle America is a clear picture of how much the basics matter: Cost of living, job quality, schools, and opportunities to develop the right skills for the best jobs. The areas within the Midwest that have gotten the basics right are poaching people and companies from the areas that haven’t. Any economic development strategy that ignores the basics in favor of a more stylized theory of growth will usually run off the rails before too long. Americans, at the end of the day, want the places they live to get the basics right so they themselves can build their lives, start their businesses, and raise their children as they wish.

This piece originally appeared at The American.

This peice was adapted from a recent report: "Clues from the Past: The Midwest as an Aspirational Region." Download the full pdf version of the report, including charts and maps about the Great Lakes Region.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

Mark Schill is Vice President of Research at Praxis Strategy Group, an economic development and research firm working with communities and states to improve their economies.

Ryan Streeter is Distinguished Fellow for Economic and Fiscal Policy at the Sagamore Institute. You can follow his work at RyanStreeter.com and Sagamoreinstitute.org.

Great Lakes Freighter photo by BigStockPhoto.com.