In an election year, politics dominates the news, but economics continue to shape people’s lives. Looking ahead to 2012 and beyond, it is clear that the United States is essentially made up of many economies, each with distinctly different short- and long-term prospects. We have highlighted the five regions that are most poised to flourish and help boost the national economy.

Our list assumes that we will be living in a post-stimulus environment. Even if President Obama is re-elected, it will largely be the result of the unattractive nature of his opposition as opposed to his economic policies. And given it is unlikely the Democrats will regain the House — and they could still lose the Senate — we are unlikely to see anything like the massive spending associated with Obama’s first two years in office.

Clearly the stimulus helped prop up certain regions, such as New York City, Washington and various university towns, which benefited from the financial bailout, lax fiscal discipline and grants to research institutions. But in the foreseeable future, fundamental economic competitiveness will be more important. Global market forces will prove more decisive than grand academic visions.

With that in mind, here are our five regions to watch in 2012.

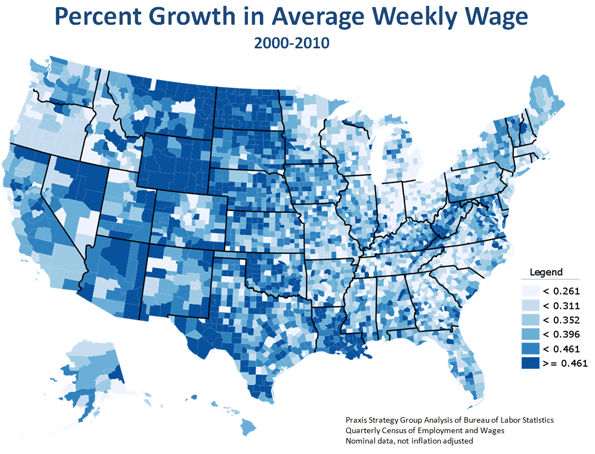

1. The Energy Belt. Even if Europe falls into recession, demand from China and other developing countries, as well as threats from Iran to cut off the Persian Gulf, will keep energy prices high. While this is bad news for millions of consumers, it could be a great boon to a host of energy-rich regions, particularly in Texas, Oklahoma, the Dakotas, Montana, Louisiana and Wyoming. New technologies that allow for greater production require higher prices than more conventional methods — roughly $70 a barrel — and most experts expect prices to stay above $100 for the next year.

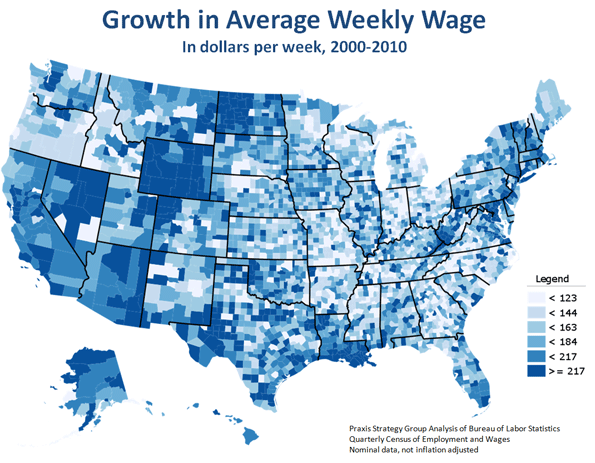

Goldman Sachs recently predicted that the U.S. will become the world’s largest oil producer by 2017. The bounty is so great that the key energy-producing states have consistently out-performed the national average in terms of job and income growth. Houston, the nation’s energy capital, has enjoyed the fastest growth in per-capita income in the past decade. No reason to expect this to slow down much this year.

Energy growth, notes Bill Gilmer, senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, also sparks “upstream” expansion in a host of other industries, such as chemicals and plastics. Massive new expansions to serve the industry are being planned not only in Texas and Louisiana but in former rust belt states, including now gas-rich Ohio. The big exception is oil-rich California, which seems determined to keep its fossil fuels — and the growth they could drive — out of mind and underground.

2. The Agricultural Heartland. You don’t have to have oil or gas to enjoy a strong economy. Omaha, Neb., is not in the energy belt, but its strong agriculture-based economy keeps its unemployment rate well under 5%. Demand from developing countries — especially China, which is expected to supplant Canada as our No. 1 agricultural market — should boost the nation’s farm income to a record $341 billion.

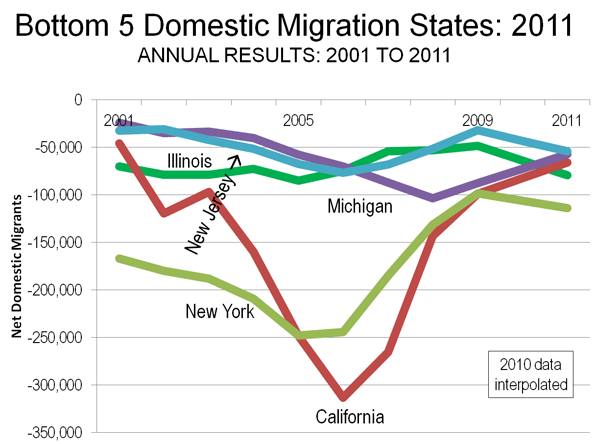

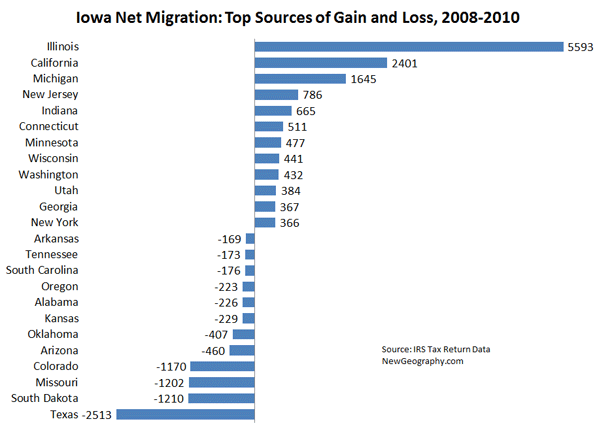

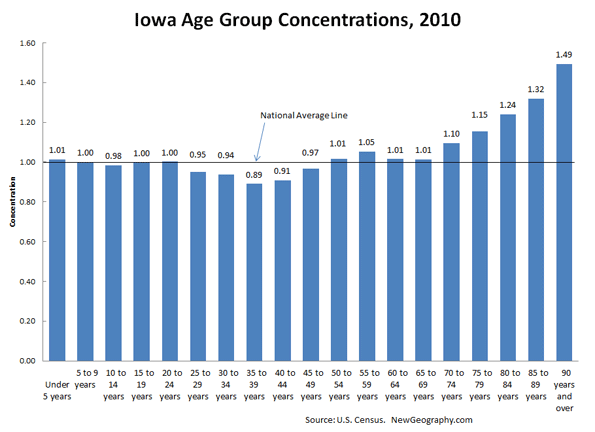

Most of the increased product demand lies in commodities like soybeans, corn, barley, rice and cotton. Contrary to the assumptions of East Coast magazines such as The Atlantic, which paint a picture of a devastated and dumb rural America, places like Iowa are doing very well indeed and are likely to continue doing so. Urban economies like Des Moines are also benefiting and expanding into finance and other non-farm related activities. The once massive out-migration from the region has slowed to something like a balance, with increasingly strong in-migration from places like Illinois and California.

3. The New Foundry. The revival of Great Lakes manufacturing is one of the heartening stories of the past year, but the biggest beneficiaries of American manufacturing’s revival will likely be in the Southeast and along the Texas corridor connected to Mexico. Future big growth will not come from bailed-out General Motors or Chrysler, with their legacy costs and still-struggling quality issues, but from foreign makers — Japanese, German and increasingly Korean — that build highly rated, energy-efficient vehicles. These countries are not just investing in cars; they also have placed steel mills and aerospace facilities in the rising south-facing foundry.

Foreign companies have good reasons to look to an expanded U.S. base: aging domestic markets, diminishing workforces and a growing concern over China’s tendency to steal technology and favor state-owned firms. This shift from domestic production has been building for years, in large part due to familiar reasons of less unionization and lower business costs. Of the ten foreign auto assembly plants opened or announced between 1997 and 2008, eight were in Southern right-to-work states. As the recovery has taken hold, new expansions are being announced. In 2011 Toyota opened a new plant in the tiny hamlet of Blue Springs, Miss., just 17 miles from Elvis’ hometown of Tupelo, while Mercedes-Benz announced $350 million to add capacity to its plant just outside of Tuscaloosa.

4. The Technosphere. Silicon Valley, as well as the Boston area, has thrived under the stimulus, and worldwide demand for technology products will continue to spark some growth in those areas. Over the past year, San Jose-Silicon Valley, Boston and Seattle all stood in the top five in job creation among the country’s 32 largest metro areas. The coming IPO for Facebook and other Valley companies may heighten the tech sector’s already smug sense of well-being.

Unfortunately for the rest of California, and even more blue-collar Bay Area communities like San Jose and Oakland, high costs and an unfavorable regulatory environment will keep this bubble geographically constrained. Historic patterns, particularly over the past decade, suggest that as the core tech companies expand, they are likely to head to business-friendly places such as Salt Lake City, Raleigh and Columbus, Ohio, which have picked up both tech companies and educated migrants from California.

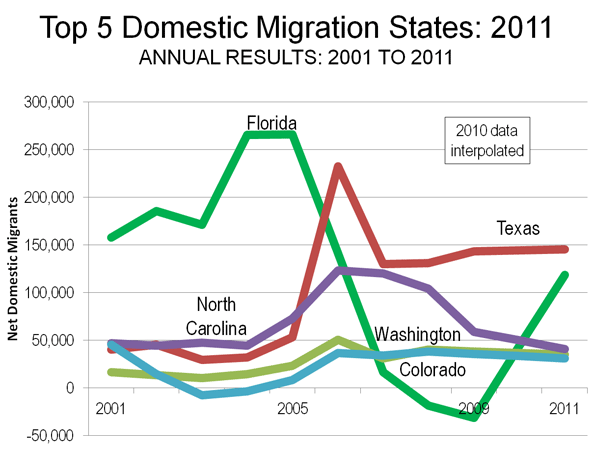

5. The Pacific Northwest. This is one blue region in the country with excellent prospects. For one thing, both Washington and Oregon enjoy considerable in-migration, in sharp contrast to New York, California and Illinois. They also have a more varied economy than Silicon Valley, with strong companies connected to retail (Amazon, Costco and Starbucks), aerospace (Boeing) and software (Microsoft).

The Seattle region, home to all these companies, is the real standout. It ranked first on our recent list of technology regions and third in industrial manufacturing, a trend likely to continue as Boeing expands production of its new 787 Dreamliner. The business climate and the housing costs are somewhat challenging, but more favorable than in California. The Bay Area and Los Angeles continue to send large numbers of migrants to the Puget Sound region. Over the long term, the area also benefits from possessing ample cheap renewable energy (mostly hydro) and water, which are both in short supply elsewhere.

These scenarios, of course, could be changed by either world events — such as an unexpected crash in the Chinese economy — or a stunning Democratic sweep in 2012 that would occasion another round of Obamaian stimulus and ever more heavy-handed regulation. Yet barring such developments, expect the back to basics economy to continue enriching these regions best positioned to take advantage of it.

This piece also appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.