It is painfully clear that the current U.S. economic recovery has been a meager one, with the benefits highly concentrated among the wealthiest. The notion that “a rising tide” lifts all boats has been sunk, along with the good ship middle class.

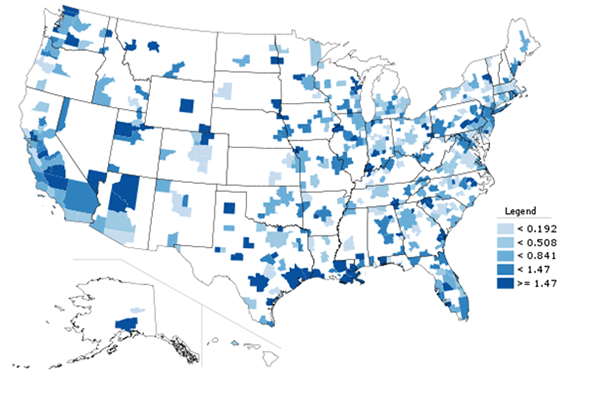

Geographically as well, the recovery has been concentrated in a relative handful of regions. Nationwide, real per capita GDP rose a meager 3.8% from 2010 through 2013, according to new Bureau of Economic Analysis numbers. An analysis of the data by urban expert Aaron Renn shows that a handful of metropolitan areas have enjoyed much faster growth. For the most part, these are areas that have cashed in on the current technology or energy booms, and in some cases, both. Also, surprisingly, there have been some very good gains in some of the nation’s long-distressed industrial heartland metro areas, as the combination of energy development and a resurgent automobile industry have boosted regional GDP.

Tech Capitals

Of the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan statistical areas, many of the top performers have strong tech economies, led by the No. 2 metro area on our list, San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, aka Silicon Valley, where real per capita GDP expanded 11.5% from 2010-13. Perhaps more surprising is the strong, tech-fuelled performance of No. 3 Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, Ore., where real per capita GDP grew 9.2%. The prime contributor has been the robust performance of late of Intel, the state’s largest private employer, which employs about 17,000 in Portland’s western suburbs around the town of Hillsboro, the company’s largest concentration of workers anywhere.

Other less heralded tech centers have also performed well, including No. 4 Columbus, Ohio (8.2% growth), and No. 8 Salt Lake City (7.3%), both of which are also benefiting from the surge in oil and gas production. Among smaller cities with strong tech communities, Fargo, N.D., and Provo-Orem, Utah, have enjoyed better than 10% real per capita GDP growth since 2010.

Energy Regions

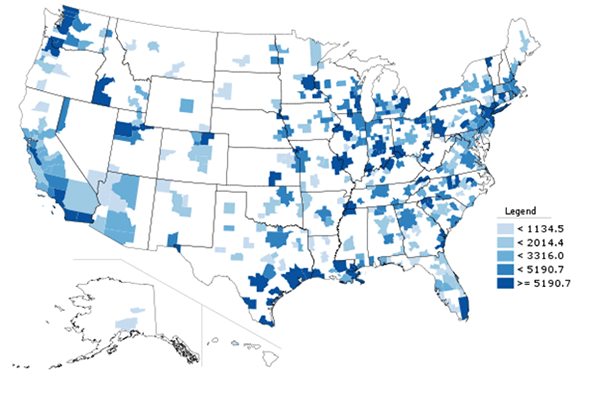

Per capita growth in the energy states has been even more impressive. Placing first on our big cities list is Houston-the Woodlands-Sugarland, Texas, where per capita GDP rose 13.2% from 2010-13, a major achievement in a region whose population continues to grow rapidly. Zooming out to all 381 U.S. MSAs, no places come close to the two Texas oil towns that rank first and second overall, Midland (sizzling 38.8% growth since 2010) and Odessa (34.1%). Both lie in the Permian basin, an oil-rich geological formation that was first tapped in the 1920s and has seen a marked revival in production recently due to advances in extraction techniques like horizontal drilling and fracking. Also notable, the southern Texas town of Victoria clocked over 21% growth.

Among the largest metro areas, energy hubs also did well, including Oklahoma City (7th, 7.5%) and Dallas-Ft. Worth-Arlington (13th, 6.5%) and the San Antonio area (16th), which is benefiting from a gusher in the Eagle Ford Shale play. Economist estimate its development has pumped $87 billion into the south Texas economy.

Rust Belt Revives

The booms in tech and energy are well-known. But the most surprising wrinkle in our survey of per capita GDP growth is the revival of auto manufacturing, which benefits both from technological improvements and lower energy costs. Among the larger metro areas, the key winners have been Grand Rapids-Wyoming (fifth, 7.8%) and Detroit (tied for ninth, 7.2%), as well as the surprising 15th place ranking for Cleveland-Elyria.

These gains are heartening, but the real question may be how long this will continue. In part, the strong 2010-13 numbers reflect a recovery from very poor economic performance that has stretched on for decades, and population losses, which tend to skew per capita GDP numbers upwards. But signs of health in the nation’s long disdained midsection deserve applause.

Surprising Laggards

The recovery has not lifted most regions, just as it has not helped most Americans. Per capita income growth has been slow in most of the nation’s largest cities outside Texas. Given the enormous financial bailout from the federal government, as well as the massive spike in stock and real estate prices, one would have expected far better performance from New York, which ranks a middling 33rd out of the 52 largest MSAs, with below average 2.3% growth since 2010.

Chicago-Naperville-Elgin ranked 26th; Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, 38th, and Philadelphia, 40th. Perhaps the biggest disappointment is 51st place Washington D.C.-Arlington-Alexandria, which had been a high-flier through the Recession amid strong federal spending. Per capita GDP since 2010 has fallen 3.4%. This disturbs some pundits, such as Richard Florida, but no doubt Washington’s fall from grace would be widely welcomed by most Americans.

And What About Poverty

Increasingly, many question not only the relative lack of growth, but that the growth we are experiencing is doing very little for the vast majority of Americans. Former Clinton adviser Bill Galston has noted that this recovery has “left almost everybody” out.

No group has been harder hit than the poor. The nation’s population below the poverty line has expanded a full percent since 2010. An analysis by demographer Wendell Cox shows that poverty declined in just seven of the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan areas from 2010-13: Louisville, Ky.; Oklahoma City; Nashville, Tenn.; Columbus Ohio; Grand Rapids; and Texas’ Austin and San Antonio.

Most of the areas with the strongest growth in per capita GDP posted smaller than average increases in poverty. In Houston the share of the population living in poverty rose 0.6% from 2010-13 to 16.4%, 11th highest among the nation’s biggest metro areas.

The results in California suggest strongly that the tech boom has not done much to relieve poverty in the Golden State, despite the much ballyhooed “California comeback” trumpeted by the likes of Paul Krugman. In reality it’s poverty, not prosperity, that’s on the march in most California cities outside the Bay Area. Since 2010, the percentage of the population of San Diego living in poverty has grown 1.3% to 15.2%, while that of Riverside-San Bernardino rose 1.7% to 18.2%, the third highest rate among the 52 largest metro areas in the country. Meanwhile the poverty rate in Los Angeles, the state’s dominant urban region, has risen 1.8% to 17.6% (fifth worst), and Sacramento, the state capital, has seen a 2.0% increase in poverty to 16.6% (10th).

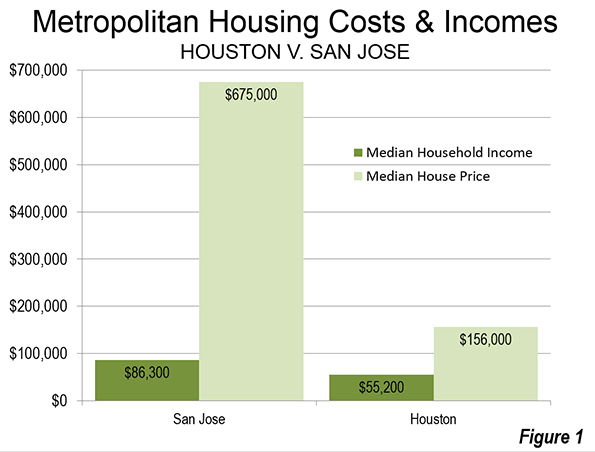

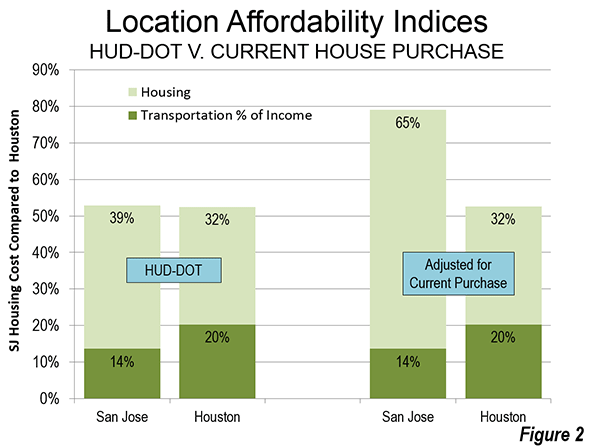

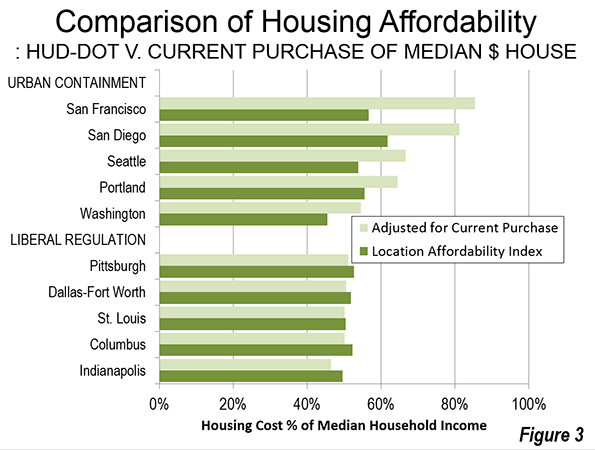

This suggests that, for the most part, what has passed for growth has been too meager to reduce poverty. In many places, even ones growing rapidly, such as the Silicon Valley hub of San Jose, the number of poor continue to increase. Since 1999, poverty in the valley has jumped from 7.6% to 10.5%. This also likely is a low figure, given the extraordinarily high cost of living in the Bay Area, as well as the rest of coastal California. According to the Census Bureau, California’s poverty rate is the highest in the nation when adjusted for the state’s exorbitant cost of housing.

For the most part, poverty has been reduced, or at least has grown less, in lower-cost regions that have ties to the energy and manufacturing revival, which tend to create opportunities for middle- and working-class residents. Until we figure out how to get growth whose benefits are widely shared, and reduce poverty, the one measurement likely to go up is cynicism about the efficacy of our current economic policies.

| Real Metropolitan Area GDP Per Capita (2010-2013) | ||||

| Rank | Metropolitan Area | 2010 | 2013 | 2010-2013 Change |

| 1 | Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land, TX | $ 63,816 | $ 72,258 | 13.2% |

| 2 | San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | $ 89,806 | $ 100,115 | 11.5% |

| 3 | Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | $ 63,025 | $ 68,810 | 9.2% |

| 4 | Columbus, OH | $ 50,370 | $ 54,493 | 8.2% |

| 5 | Grand Rapids-Wyoming, MI | $ 41,248 | $ 44,482 | 7.8% |

| 6 | Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, NC-SC | $ 51,819 | $ 55,802 | 7.7% |

| 7 | Oklahoma City, OK | $ 45,993 | $ 49,441 | 7.5% |

| 8 | Salt Lake City, UT | $ 57,790 | $ 62,008 | 7.3% |

| 9 | Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | $ 50,464 | $ 54,112 | 7.2% |

| 10 | Detroit-Warren-Dearborn, MI | $ 46,314 | $ 49,653 | 7.2% |

| 11 | Pittsburgh, PA | $ 48,710 | $ 52,053 | 6.9% |

| 12 | Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN | $ 48,841 | $ 52,063 | 6.6% |

| 13 | Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | $ 57,032 | $ 60,730 | 6.5% |

| 14 | Birmingham-Hoover, AL | $ 46,108 | $ 49,034 | 6.3% |

| 15 | Cleveland-Elyria, OH | $ 52,169 | $ 55,430 | 6.3% |

| 16 | San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX | $ 37,202 | $ 39,280 | 5.6% |

| 17 | San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, CA | $ 75,103 | $ 78,844 | 5.0% |

| 18 | Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | $ 71,404 | $ 74,701 | 4.6% |

| 19 | Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | $ 59,168 | $ 61,711 | 4.3% |

| 20 | Sacramento–Roseville–Arden-Arcade, CA | $ 43,905 | $ 45,764 | 4.2% |

| 21 | Austin-Round Rock, TX | $ 50,094 | $ 52,110 | 4.0% |

| 22 | Denver-Aurora-Lakewood, CO | $ 59,284 | $ 61,595 | 3.9% |

| 23 | Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ | $ 43,156 | $ 44,803 | 3.8% |

| 24 | Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH | $ 71,936 | $ 74,643 | 3.8% |

| 25 | San Diego-Carlsbad, CA | $ 55,921 | $ 57,955 | 3.6% |

| 26 | Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI | $ 55,727 | $ 57,752 | 3.6% |

| 27 | Providence-Warwick, RI-MA | $ 41,698 | $ 42,994 | 3.1% |

| 28 | Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN | $ 46,710 | $ 48,048 | 2.9% |

| 29 | Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL | $ 39,066 | $ 40,153 | 2.8% |

| 30 | Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls, NY | $ 41,497 | $ 42,550 | 2.5% |

| 31 | Baltimore-Columbia-Towson, MD | $ 55,907 | $ 57,294 | 2.5% |

| 32 | Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson, IN | $ 58,590 | $ 60,038 | 2.5% |

| 33 | New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA | $ 67,499 | $ 69,074 | 2.3% |

| 34 | Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA | $ 26,509 | $ 27,094 | 2.2% |

| 35 | St. Louis, MO-IL | $ 47,876 | $ 48,738 | 1.8% |

| 36 | Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | $ 55,767 | $ 56,734 | 1.7% |

| 37 | Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach, FL | $ 44,386 | $ 45,145 | 1.7% |

| 38 | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA | $ 58,211 | $ 59,092 | 1.5% |

| 39 | Kansas City, MO-KS | $ 52,916 | $ 53,677 | 1.4% |

| 40 | Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | $ 58,696 | $ 59,339 | 1.1% |

| 41 | Memphis, TN-MS-AR | $ 46,534 | $ 47,014 | 1.0% |

| 42 | Richmond, VA | $ 50,977 | $ 51,498 | 1.0% |

| 43 | Rochester, NY | $ 44,825 | $ 45,202 | 0.8% |

| 44 | Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA | $ 51,830 | $ 52,178 | 0.7% |

| 45 | Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC | $ 48,395 | $ 48,708 | 0.6% |

| 46 | Raleigh, NC | $ 51,820 | $ 51,673 | -0.3% |

| 47 | Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, NV | $ 43,351 | $ 43,079 | -0.6% |

| 48 | Jacksonville, FL | $ 42,068 | $ 41,752 | -0.8% |

| 49 | Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT | $ 68,005 | $ 66,870 | -1.7% |

| 50 | Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL | $ 47,023 | $ 45,855 | -2.5% |

| 51 | Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | $ 76,035 | $ 73,461 | -3.4% |

| 52 | New Orleans-Metairie, LA | $ 61,325 | $ 56,943 | -7.1% |

| Analysis by Aaron M. Renn | ||||

This piece first appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Photo by w:Flickr user Bill Jacobus [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons