For years both government and media have been advancing the notion that America’s coastal counties are obtaining most of the population growth at the expense of interior counties. For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported in the 1990s: Coastal areas are crowded and becoming more so every day. More than 139 million people–about 53% of the national total–reside along the narrow coastal fringes.

NOAA went on to say that the population of the coastal counties is expected to increase by an average of 3600 people per day and noted further that the coastal counties were growing faster than the nation as a whole. NOAA has designated 673 counties on four coasts (Atlantic, Gulf, Pacific and Great Lakes) in the contiguous United States, Hawaii and Alaska as coastal counties.

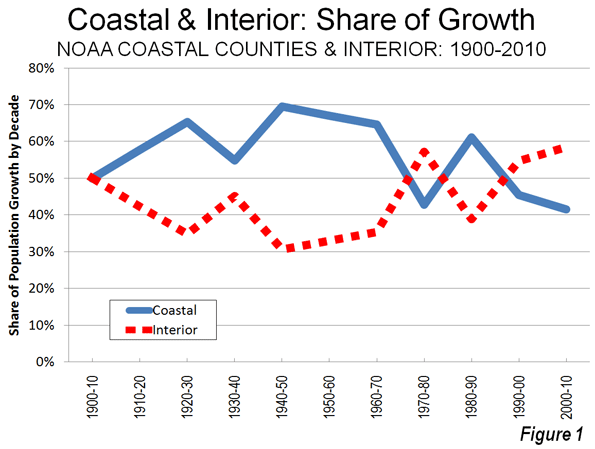

Population Growth: In fact, coastal counties are not growing faster than the nation as a whole and were not when NOOA issued the 1990s report. For most of the last 40 years, the nation’s interior counties have been adding more population. From 1970 to 2010, interior counties added 55.7 million new residents, compared to 49.7 million new residents in coastal counties. This is a reversal from 1940 to 1970, when two thirds of the nation’s population growth was in the coastal counties.

The trends today actually have become more favorable for the interior than at any time in a century. From 2000 to 2010, the interior counties captured more of the nation’s growth than in any decade since 1900 (Table). From 2000 to 2010, the interior counties added 16.0 million residents, 59.6 percent of the nation’s growth compared to 11.4 million new residents in the coastal counties.

| Coastal and Interior Population: Counties | ||||||||

| 1900-2010 | ||||||||

| Coastal Counties | Interior Counties | United States | ||||||

| Year | Population | Share | Change | Population | Share | Change | Population | Change |

| 1900 | 30.2 | 39.7% | 46.0 | 60.3% | 76.2 | |||

| 1910 | 38.2 | 41.4% | 8.0 | 54.0 | 58.6% | 8.0 | 92.2 | 16.0 |

| 1920 | 46.2 | 43.6% | 8.0 | 59.8 | 56.4% | 5.8 | 106.0 | 13.8 |

| 1930 | 57.4 | 46.6% | 11.2 | 65.8 | 53.4% | 6.0 | 123.2 | 17.2 |

| 1940 | 62.3 | 47.1% | 4.9 | 69.8 | 52.9% | 4.0 | 132.2 | 9.0 |

| 1950 | 75.2 | 49.9% | 12.9 | 75.5 | 50.1% | 5.7 | 150.7 | 18.5 |

| 1960 | 94.4 | 52.6% | 19.2 | 85.0 | 47.4% | 9.5 | 179.3 | 28.6 |

| 1970 | 109.9 | 54.0% | 15.6 | 93.5 | 46.0% | 8.5 | 203.4 | 24.1 |

| 1980 | 119.8 | 52.9% | 9.9 | 106.7 | 47.1% | 13.2 | 226.5 | 23.2 |

| 1990 | 133.4 | 53.6% | 13.6 | 115.3 | 46.4% | 8.6 | 248.7 | 22.2 |

| 2000 | 148.2 | 52.7% | 14.9 | 133.2 | 47.3% | 17.9 | 281.4 | 32.7 |

| 2010 | 159.6 | 51.7% | 11.4 | 149.1 | 48.3% | 16.0 | 308.7 | 27.3 |

| Population in Millions | ||||||||

| Calculated from US Census Bureau Data | ||||||||

| Coastal counties designated by NOAA (673 counties) | ||||||||

| Totals may vary due to rounding | ||||||||

As of 2010, the coastal counties have 51.7 percent of the nation’s population, having dropped from 52.7 percent in 2000 and a peak of 54.0 percent in 1970 (Figure 1). Rather than adding 3600 new people every day, coastal counties added 3100 people per day, while interior counties added 4400 per day during the 2000s. A smaller sample of 559 counties that was examined by economists Jordan Rapaport and Jeffrey Sachs in the early 2000s experienced an even more pronounced movement away from the coasts between 2000 and 2010, with more than 60 percent of the nation’s growth taking place in the interior counties.

There may also be some concern about density in coastal counties. Yet Malthusian fears need not grip coastal residents. With a population density of approximately 315 per square mile (120 per square kilometer), the coastal counties of the contiguous United States have only a slightly higher density than the post-enlargement 27-nation European Union. The coastal counties have a density one-half that of Germany. In contrast, the interior counties are far less dense, at 60 persons per square mile.

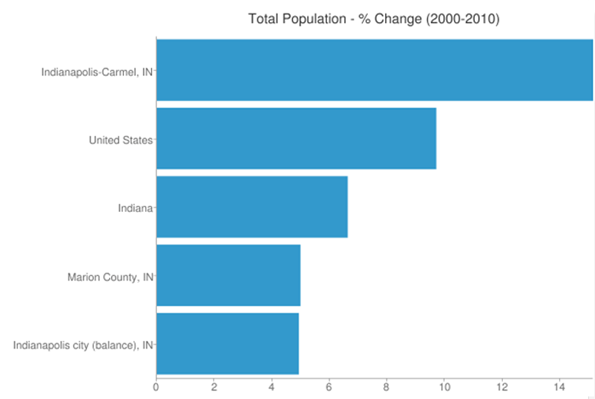

There has also been significant change in coastal population trends since the middle 1990s. The largest Pacific Coast metropolitan areas, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego, San Jose and Seattle have seen their growth slow considerably. In the 1990s, NOAA was projecting huge population increases for Los Angeles and San Diego counties. It appears likely that these 2015 projections will fall at least 600,000 short in both counties. Even Seattle, arguably the healthiest economically among the west coast metropolitan areas, is now growing more slowly than former laggards Oklahoma City, Indianapolis and Columbus in the interior.

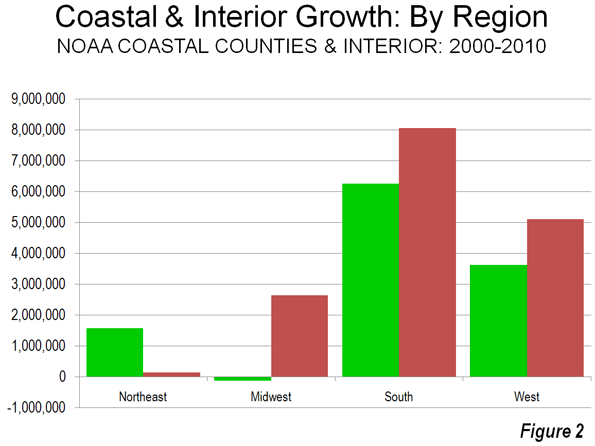

Regional Population Growth: There was significant variation in growth among the varied regions of the country. In the Northeast, there was much stronger growth on the coast, which added 1.6 million people, compared to a gain of less than 150,000 in the interior. In the Midwest, the coastal counties (along the Great Lakes) lost 120,000 people, while the interior counties gained 2.7 million. In the South, the interior grew more, at 8.1 million, slightly more than 6.3 million in coastal counties. In the West, interior counties gained 5.1 million people, while the coastal counties gained 3.7 million (Figure 2). This drop in coastal growth was a principal reason why the West grew less quickly than the South, which experienced the most robust coastal growth. For this reason, the West failed to be the nation’s fastest growing region for the first time since 1900.

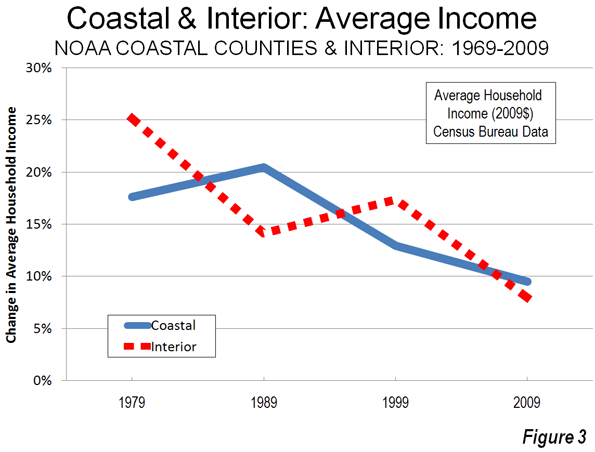

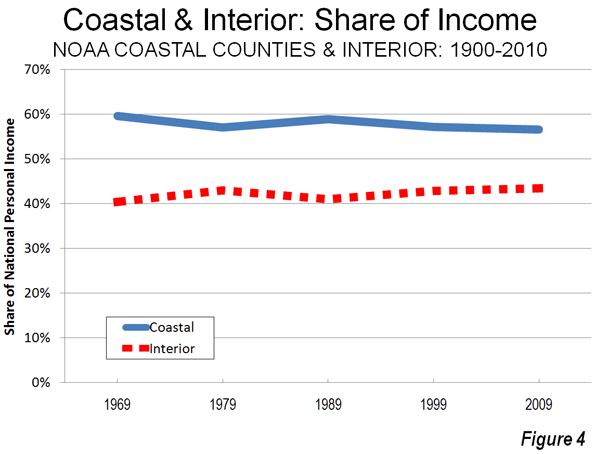

Personal Income: Rappaport and Sachs noted in their early 2000s work that the density of economic activity was far greater in the coastal counties. Of course this is to be expected, due to their greater population density. However the data with respect to the distribution of personal income is less clear. Since 1969, coastal and interior counties have been alternating leadership in personal income growth per capita. During the 2000s, interior counties experienced average personal income growth slightly less than that of the coastal counties (Figure 3). However, average per capita income since 1970 has risen 81 percent, compared to a lower 75 percent in the coastal counties (adjusted for inflation). Overall, the share of income in the interior counties has been growing modestly (Figure 4).

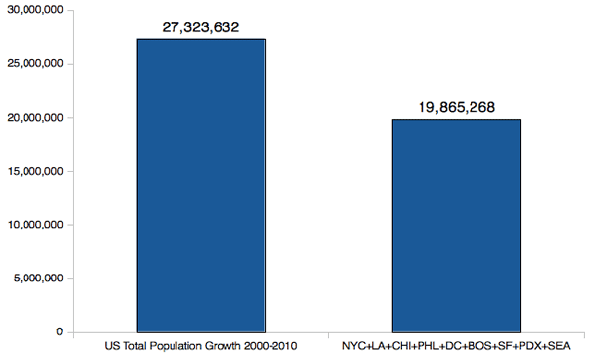

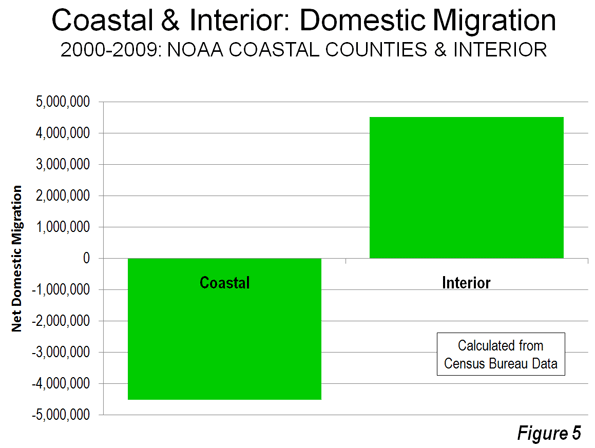

Domestic Migration: The most important factor in the growth of the interior counties in the 2000s lies with net domestic migration, with more residents moving from the coastal counties to the interior counties. Between 2000 and 2009, 4.5 million people moved to the interior counties, while 4.5 million people moved away from the coastal counties, according to Census Bureau estimates (Figure 5).

Rappaport and Sachs had theorized that the greater concentration of population and economic activity in the coastal counties could be reflective of a more attractive quality of life. The domestic migration data would suggest that, at least over the last decade, people are opting for the interior, perhaps sensing that the coastal quality of life may not be as affordable and accessible as in the past.

Cost of Living: The key here lies with the cost of living, which has become far higher on the coasts then in the interior. The most significant cost of living differences for households are in the cost of housing.

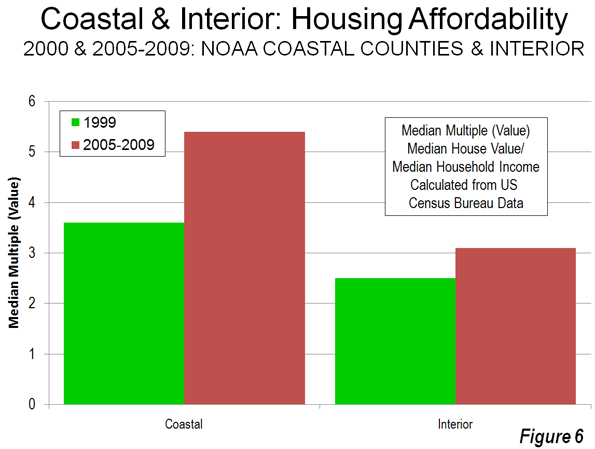

From 2000 to 2009, housing affordability deteriorated markedly in the coastal counties. Census Bureau data indicates that the Median Multiple (median house founded divided by median household income) rose from 3.6 to 5.4 in the coastal counties (population weighted). By contrast, housing affordability worsened far less in the interior counties, where the Median Multiple rose from 2.5 to 3.1. Thus, the median household saw owned housing increase 22 months worth of income in value in coastal counties, compared to seven months worth of income in interior counties (Figure 6). At the same time, these higher coastal house prices developed as demand for housing was dropping substantially, with 4.5 million people moving away from coastal counties (above).

Many of the coastal counties have strong land use regulation (smart growth or urban containment regulation), especially in California, Oregon, Washington, Florida and the metropolitan areas of Boston, New York and Washington. A considerable body of research, both econometric and descriptive, has associated more restrictive land use regulation (called smart growth, urban consolidation or urban containment) with higher house price increases, reaching back at least to the seminal 1970s work by Sir Peter Hall and his associates in the United Kingdom. It thus seems likely that the deterioration of housing affordability in coastal counties is materially associated with their less robust growth. The quality of life on the coasts may simply have become too expensive.

The Future? It is unclear whether the recent higher population growth rates, stronger migration trends and improved economic performance of the interior will continue into the future. The 1940 to 1970 dominance of the coastal counties surged as coastal metropolitan areas, especially in Florida and California, grew much more quickly. Now that pattern has been reversed. More favorable trends over the past 40 years in the interior counties seem likely continue, unless coastal house prices and the cost of living begin to swing back toward the national norm.

—-

Note: Complete county data is at County Coastal Population (also attached to this article)

Photograph: San Diego, which experienced greater domestic outmigration than Pittsburgh in the 2000s.

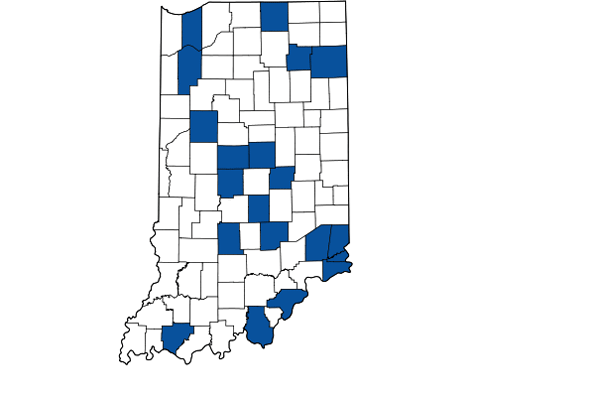

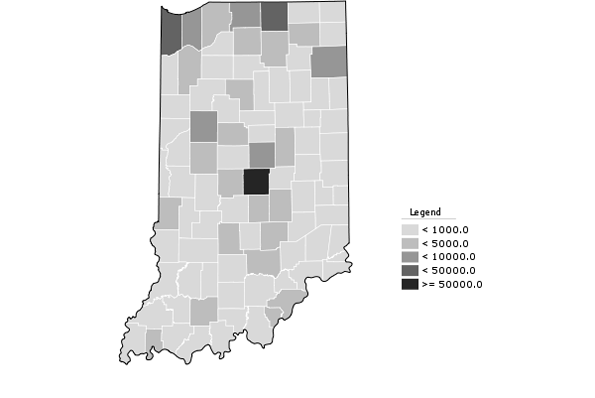

Indy’s Asian population also more than doubled to almost 40,000.. Add this all up and the metro area non-Hispanic white-only population share dropped by six percentage points, but remains at 74.6%. The city of Indianapolis itself is pushing 40% minority, however. Regardless, this is still a material change and shows that metro Indy is a strong magnet not just for whites, but for pretty much everybody. Its challenge is to continue building on this for the future, while the state’s challenge will be to pull itself up to Indy’s level of demographic and economic performance.

Indy’s Asian population also more than doubled to almost 40,000.. Add this all up and the metro area non-Hispanic white-only population share dropped by six percentage points, but remains at 74.6%. The city of Indianapolis itself is pushing 40% minority, however. Regardless, this is still a material change and shows that metro Indy is a strong magnet not just for whites, but for pretty much everybody. Its challenge is to continue building on this for the future, while the state’s challenge will be to pull itself up to Indy’s level of demographic and economic performance.