For some time, theorists have been suggesting that it is time to redefine the American Dream of home ownership. Households, we are told, should live in smaller houses, in more crowded neighborhoods and more should rent. This thinking has been heightened by the mortgage crisis in some parts of the country, particularly in areas where prices rose most extravagantly in the past decade. And to be sure, many of the irrational attempts – many of them government sponsored – to expand ownership to those not financially prepared to bear the costs need to curbed.

But now the anti-homeowner interests have expanded beyond reigning in dodgy practices and expanded into an argument essentially against the very idea of widespread dispersion of property ownership. Social theorist Richard Florida recently took on this argument, in a Wall Street Journal article entitled “Home Ownership is Overvalued.”

In particular, he notes that:

The cities and regions with the lowest levels of homeownership—in the range of 55% to 60% like L.A., N.Y., San Francisco and Boulder—had healthier economies and higher incomes. They also had more highly skilled and professional work forces, more high-tech industry, and according to Gallup surveys, higher levels of happiness and well-being. (Note)

Florida expresses concern that today’s economy requires a more mobile work force and is worried that people may be unable to sell their houses to move to where jobs can be found. Those who would reduce home ownership to ensure mobility need lose little sleep.

The Relationship Between Household Incomes and House Prices

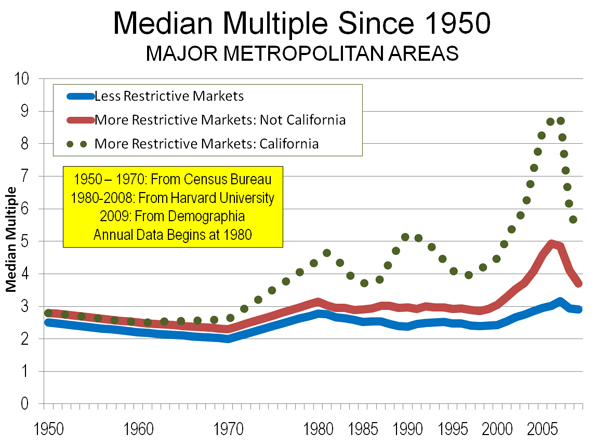

It is true, as Florida indicates, that house prices are generally higher where household incomes are higher. But, all things being equal, there are limits to that relationship, as a comparison of median house prices to median house prices (the Median Multiple) indicates. From 1950 to 1970 the Median Multiple averaged three times median household incomes in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas. In the 1950, 1960 and 1970 censuses, the most unaffordable major metropolitan areas reached no higher than a multiple of 3.6 (Figure).

This changed, however, in some areas after 1970, spurred by higher Median Multiples occuring in California.

William Fischel of Dartmouth has shown how the implementation of land use controls in California metropolitan areas coincided with the rise of house prices beyond historic national levels. The more restrictive land use regulations rationed land for development, placed substantial fees on new housing, lengthened the time required for project approval and made the approval process more expensive. At the same time, smaller developers and house builders were forced out of the market. All of these factors (generally associated with “smart growth”) propelled housing costs higher in California and in the areas that subsequently adopted more restrictive regulations (see summary of economic research).

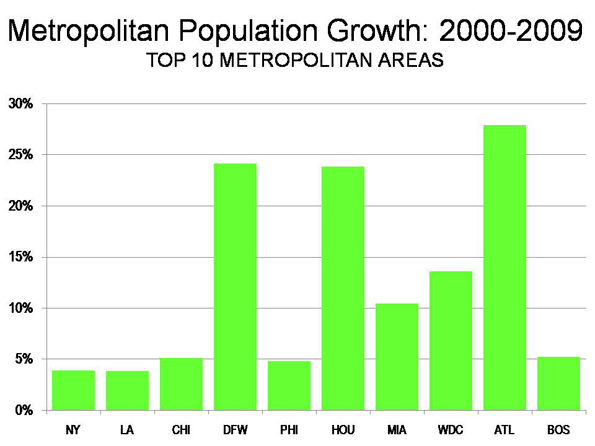

During the bubble years, house prices rose far more strongly in the more highly regulated metropolitan areas than in those with more traditional land use regulation. Ironically many of the more regulated regions experienced both slower job and income growth compared to more liberally regulated areas, notably in the Midwest, the southeast, and Texas.

Home Ownership and Metropolitan Economies

The major metropolitan areas Florida uses to demonstrate a relationship between higher house prices and “healthier economies” are, in fact, reflective of the opposite. Between August 2001 and August 2008 (chosen as the last month before 911 and the last month before the Lehman Brothers collapse), Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicates that in the New York and Los Angeles metropolitan areas, the net job creation rate trailed the national average by one percent. The San Francisco area did even worse, trailing the national net job creation rate by 6 percent, and losing jobs faster than Rust Belt Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Milwaukee.

Further, pre-housing bubble Bureau of Economic Analysis data from the 1990s suggests little or no relationship between stronger economies and housing affordability as measured by net job creation. The bottom 10 out of the 50 largest metropolitan areas had slightly less than average home ownership (this bottom 10 included “healthy” New York and Los Angeles). The highest growth 10 had slightly above average home ownership (measured by net job creation). Incidentally, “healthy” San Francisco also experienced below average net job creation, ranking in the fourth 10.

Moreover, housing affordability varied little across the categories of economic growth (Table).

| Net Job Creation, Housing Affordability & Home Ownership | |||

| Pre-Housing Bubble Decade: Top 50 Metropolitan Areas (2000) | |||

| Net Job Creation: 1990-2000 | Housing Affordability: Median Multiple (2000) | Home Ownership: Rate 2000 | |

| Lowest Growth 10 | 7.4% | 2.8 | 62% |

| Lower Growth 10 | 14.9% | 3.1 | 63% |

| Middle 10 | 22.8% | 3.2 | 64% |

| Higher Growth 10 | 30.9% | 2.6 | 61% |

| Highest Growth 10 | 46.9% | 2.9 | 63% |

| Average | 24.7% | 2.9 | 62% |

| Calculated from Bureau of the Census, Bureau of Economic Analysis and Harvard Joint Housing Center data. | |||

| Metropolitan areas as defined in 2003 | |||

| Home ownership from urbanized areas within the metropolitan areas. | |||

Home Ownership and Happiness

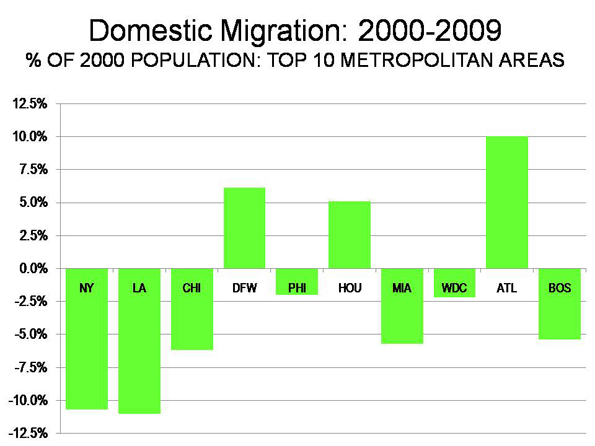

If Gallup Polls on happiness were reliable, it would be expected that the metropolitan areas with happier people would be attracting people from elsewhere. In fact, people are fleeing with a vengeance. During this decade alone, approximately one in every 10 residents have left for other areas.

- The New York metropolitan area lost nearly 2,000,000 domestic migrants (people who moved out of the metropolitan area to other parts of the nation). This is nearly as many people as live in the city of Paris.

- The Los Angeles metropolitan area has lost a net 1.35 million domestic migrants. This is more people than live in the city of Dallas.

- The San Francisco metropolitan area lost 350,000 domestic migrants. Overall, the Bay Area (including San Jose) lost 650,000, more people than live in the cities of Portland or Seattle.

Why have all of these happy people left these “healthy economies?” One reason may be that so many middle income people find home ownership unattainable is due to the house prices that rose so much during the bubble and still remain well above the historic Median Multiple. People have been moving away from the more costly metropolitan areas. Between 2000 and 2007:

- 2.6 million net domestic migrants left the major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population) with higher housing costs (Median Multiple over 4.0).

- 1.1 net domestic migrants moved to the major metropolitan areas with lower house prices (Median Multiple of 4.0 or below).

- 1.6 million domestic migrants moved to small metropolitan areas and non-metropolitan areas (where house prices are generally lower).

An Immobile Society?

Florida’s perceived immobility of metropolitan residents is curious. Home ownership was not a material barrier to moving when tens of millions of households moved from the Frost Belt to the Sun Belt in the last half of the 20th century. During the 2000s, as shown above, millions of people moved to more affordable areas, at least in part to afford their own homes.

Under normal circumstances (which will return), virtually any well-kept house can be sold in a reasonable period of time. More than 750,000 realtors stand ready to assist in that regard.

Of course, one of the enduring legacies of the bubble is that many households owe more on their houses than they are worth (“under water”). This situation, fully the result of “drunken sailor” lending policies, is most severe in the overly regulated housing markets in which prices were driven up the most. Federal Reserve Bank of New York research indicates that the extent of home owners “under water” is far greater in the metropolitan markets that are more highly restricted (such as San Diego and Miami) and is generally modest where there is more traditional regulation, such as Charlotte and Dallas (the exception is Detroit, caught up in a virtual local recession, and where housing prices never rose above historic norms, even in the height of the housing bubble). Doubtless many of these home owners will find it difficult to move to other areas and buy homes, especially where excessive land use regulations drove prices to astronomical levels.

Restoring the Dream

There is no need to convince people that they should settle for less in the future, or that the American Dream should be redefined downward. Housing affordability has remained generally within historic norms in places that still welcome growth and foster aspiration, like Atlanta, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Columbus and elsewhere for the last 60 years, including every year of the housing bubble. Rather than taking away the dream, it would be more appropriate to roll back the regulations that are diluting the purchasing power and which promise a less livable and less affluent future for altogether too many households.

—

Note. Among these examples, New York is the largest metropolitan area in the nation. Los Angeles ranks number 2 and San Francisco ranks number 13. The inclusion of Boulder, ranked 151st in 2009 seems a bit curious, not only because of its small size, but also because its advantage of being home to the main campus of the University of Colorado. Smaller metropolitan areas that host their principal state university campuses (such as Boulder, Eugene, Madison or Champaign-Urbana) will generally do well economically.

Photograph: New house currently priced at $138,990 in suburban Indianapolis (4 bedroom, 2,760 square feet). From http://www.newhomesource.com/homedetail/market-112/planid-823343

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”