The late comedian Rodney Dangerfield (nee Jacob Cohen), whose signature complaint was that he “can’t get no respect,” would have fit right in, in the Inland Empire. The vast expanse east of greater Los Angeles has long been castigated as a sprawling, environmental trash heap by planners and pundits, and its largely blue-collar denizens denigrated by some coast-dwellers, including in Orange County, who fret about “909s” – a reference to the IE’s area code – crowding their beaches.

The Urban Dictionary typically defines the region as “a great place to live between Los Angeles and Las Vegas if you don’t mind the meth labs, cows and dirt people.” Or, as another entry put it, a collection of “worthless idiots, pure and simple.” Nice.

In reality, the people who live along the coast should appreciate the “909ers” since they constitute the future – if there is much of one – for Southern California’s middle class. The region has suffered considerably since the Great Recession, in part because of a high concentration of subprime loans taken out on new houses. Yet, for all its problems, the Inland Empire has remained the one place in Southern California where working-class and middle-class people can afford to own a home. With a median multiple (median house price divided by household income) of roughly 3.7, the area is at least 40 percent less expensive than Los Angeles and Orange County, making it the region’s last redoubt for the American dream.

Without the 909ers, Southern California would be demographically stagnant. From 2000-10, according to the census, San Bernardino and Riverside counties added more than 1 million people, compared with barely 200,000 combined for Los Angeles and Orange counties. And, despite the downturn that impacted the Inland Empire severely and slowed its growth, the area since 2010 has continued to grow more quickly, according to census estimates, than the coastal counties.

Families & foreign-born

Perhaps nothing illustrates the appeal of the region better than the influx of the foreign-born. In the past decade, Riverside and San Bernardino counties grew their foreign-born population by more than 300,000. In contrast, Los Angeles and Orange added barely one third as many. The rate of foreign-born growth in the Inland Empire, notes demographer Wendell Cox, was roughly 50 percent, while Los Angeles and Orange counties managed 2.6 percent growth. The region, once largely white, now has a population that’s 40 percent Latino, the single largest ethnic group.

And then there’s families. As demographer Ali Modarres has pointed out, the populations of Los Angeles, as well as Orange County, are aging rapidly while the numbers of children have dropped. In contrast, families continue to move into the Inland Empire, one reason for its relatively vibrant demography. Over the past decade, while Orange County and Los Angeles experienced a combined loss of 215,000 people under age 14 – among the highest rates in the U.S. of a shrinking population of children – the Inland Empire gained more than 20,000 under-14s.

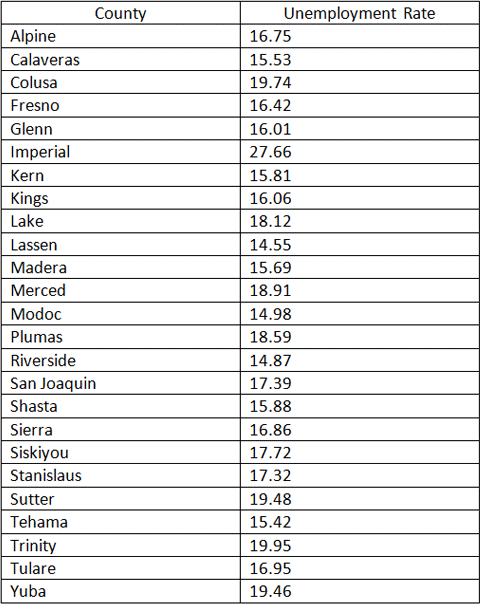

For these basic demographic reasons, the Inland Empire remains critical to Southern California’s success. And there are some signs of progress. Unemployment has plummeted from more than 13 percent to 9.6 percent, higher than in Orange County but considerably better than Los Angeles’ 10.2 percent. There are also some signs of growth, as signaled by some new residential development, and interest in the area from overseas investors.

Coastals call shots

The long-term outlook, however, remains clouded, in large part, because of state and regional economic policies that undermine the very nature of the predominately blue-collar 909 economy. This reflects in part the domination of the state by the coastal political class, concentrated in the Bay Area but with strong support in many Southern California coastal communities. The Inland Empire, where almost half the population has earned a high school degree or less, compared with a third of residents in Orange County, is particularly dependent on the blue-collar employment undermined by the gentry-oriented direction of state regulatory policy.

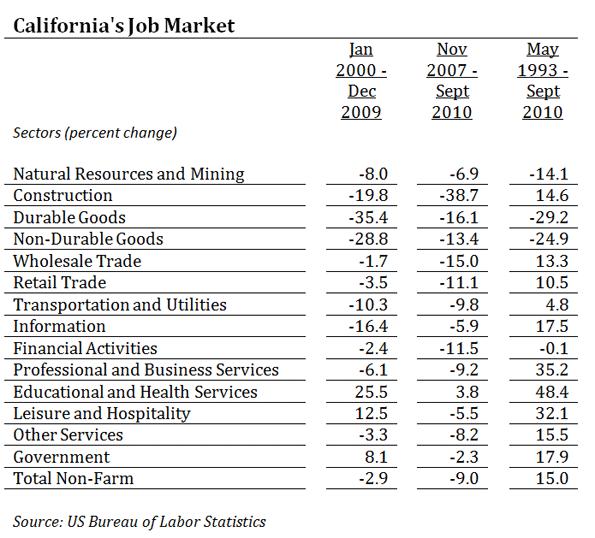

Losses of jobs in these blue-collar fields, notes economist John Husing, have helped swell the ranks of poor people in the area, from roughly 12 percent of the population to 18 percent over the past 20 years. Part of the problem lies in a determination by the state to discourage precisely the kind of single-family-oriented suburban development that has attracted so many to the region. The decline of construction jobs – some 54,000 during the recession – hit the region hard, particularly its heavily immigrant, blue-collar workforce. This sector has made only a slight recovery in recent months. Ironically, the nascent housing recovery could short-circuit further gains by boosting housing prices and squashing any potential longer-term recovery.

Other state policies – such as cascading electricity prices – also hit the Inland Empire’s once-promising industrial economy. With California electricity prices as much as two times higher than those in rival states, energy-consuming industries are looking further east, beyond state lines.

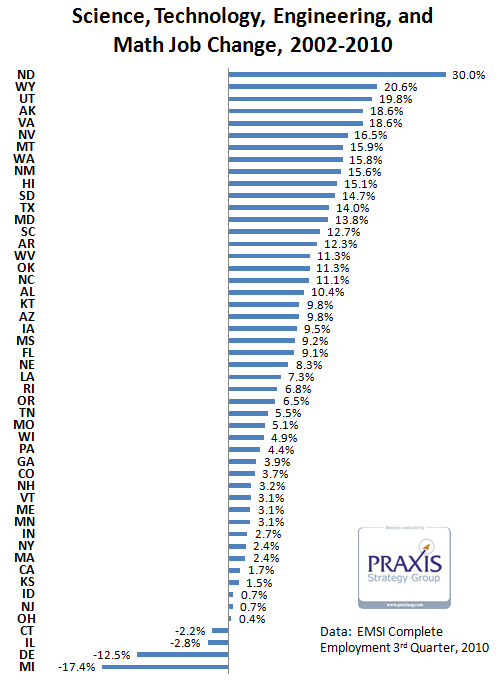

Indeed, according to recent economic trends, job growth is now occurring fastest in places like Arizona, Texas, even Nevada, all of which compete directly with the Inland Empire. As the nation has gained a half-million manufacturing jobs since 2010, such jobs have continued to leave the region. Had the regulatory environment been more favorable, notes economist John Husing, the Inland Empire, with industrial space half as expensive that in Los Angeles and Orange, would have been a major beneficiary.

Finally, there is a major threat to the logistics industry, which has grown rapidly over 20 years, adding 71,900 jobs from 1990-2012, a yearly average of 3,268. The potential threat is posed by the expansion of the Panama Canal, and the resulting expansion of Gulf Coast ports, all of which could reduce these positions dramatically in coming decades. Husing suggests that attempts by the regional Air Quality Management District to slow this industry’s expansion is a “a fundamental attack on the area’s economic health.”

Keys to rebound

Can the Inland Empire still make another turnaround, as it did after the previous deep regional recession 20 years ago? Some, such as the Los Angeles Times, see the key to a rebound in boosting transit, something that, despite huge investment, accounts for barely 1.5 percent of the IE’s work trips, even less than the 7 percent in Los Angeles or 3 percent in Orange County.

This “smart growth” solution remains oddly detached from economic or geographic reality; more transit usage may be preferable in some ways but can only constitute a marginal factor in the near or midterm future. What the Inland Empire needs, more than anything, is an economic environment that spurs middle-class jobs, notably in logistics, manufacturing and construction.

Equally important, the area needs to focus more on quality-of-life issues that may attract younger, educated workers, increasingly priced out of the coastal areas. This means a commitment to better parks and schools, attractive particularly to families. This approach has helped a few communities, such as Eastvale, near Ontario, become new bastions of the middle class.

Without a resurgence in the Inland Empire, all of Southern California can expect, at best, to see the area age and lose its last claim to vitality. This should matter to everyone in Southern California whether they live there or not. Without the 909ers, we are not only without the butt of jokes from self-styled sophisticates, we will have lost touch with the very aspirational dynamic that has forged this region throughout its history. It’s time maybe to give them some respect.

This story originally appeared at The Orange County Register.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.