Economists, planners and the media often focus on the extremes of real estate — the high-end properties or the foreclosed deserts, particularly in the suburban fringe. Yet to a large extent, they ignore what is arguably the most critical issue: affordability.

This problem is the focus of an important new study by Demographia. The study, which focuses largely on English-speaking countries, looks at the price of housing relative to household income. It essentially benchmarks the number of years of a region’s household income required to purchase a median-priced house.

Overall, the results are rather dismal in terms of affordability, particularly in what Wharton’s Joe Gyourko dubs “superstar cities.” These places — such as London, New York, Sydney, Toronto and Los Angeles — generally tend to be more expensive than second-tier regions commonly found in the American South and heartland.

Even with their usually higher incomes, these regions, for the most part, still have a ratio of five years median income to median house price; this is far higher than the historical ratio of three. In some areas the ratios are even more stratospheric. Sydney and Melbourne, for example, have ratios over nine; London, New York, San Jose and Los Angeles approach six or more.

Urbanists often assume that these high prices — unprecedented in a tepid economy — reflect the greater attractiveness of these regions. This is somewhat true, particularly for parts of London and New York, which can survive high ratios because their markets are less national and middle-income and more tied to the global upper classes.

In places like Mayfair or New York’s Upper East Side, the buying “public” extends beyond the local market to high-income markets in places like the United Arab Emirates, Moscow, Shanghai, Singapore or Tokyo. Many owners are not full-time residents and consider a home in such places as just another expression of their wealth and privilege.

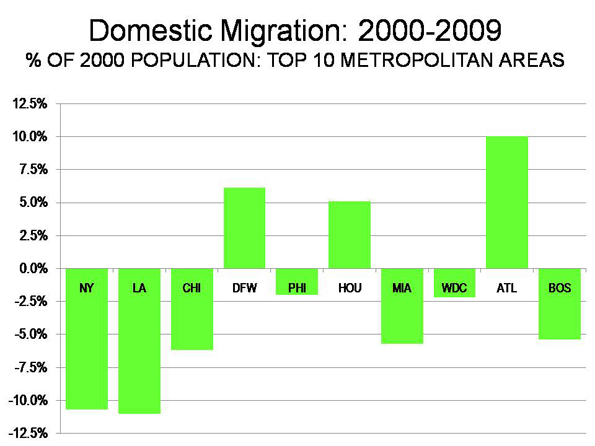

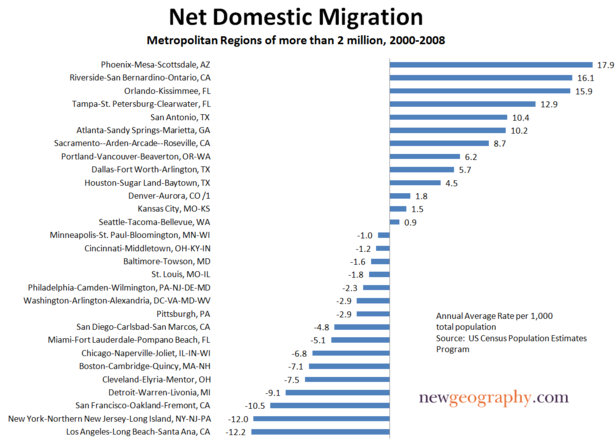

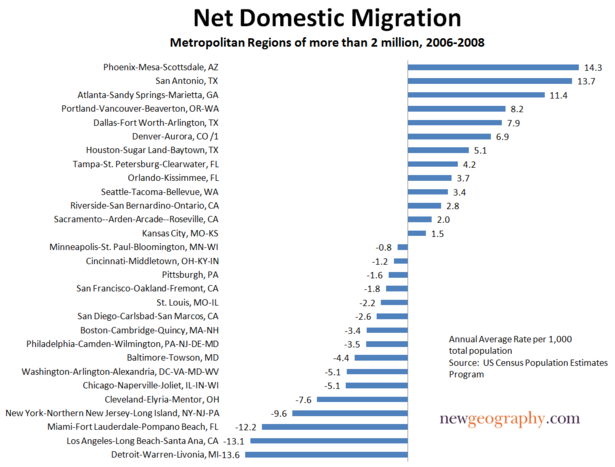

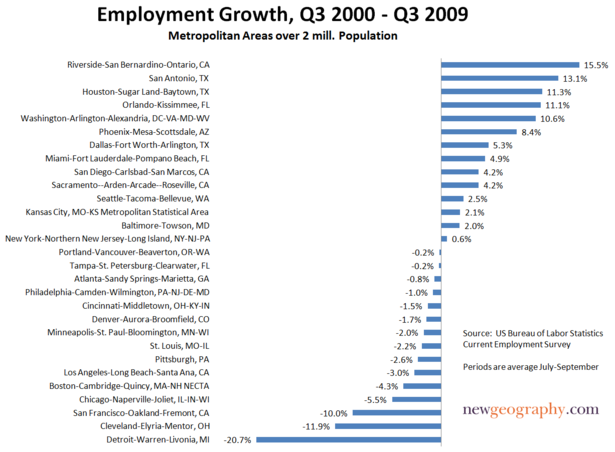

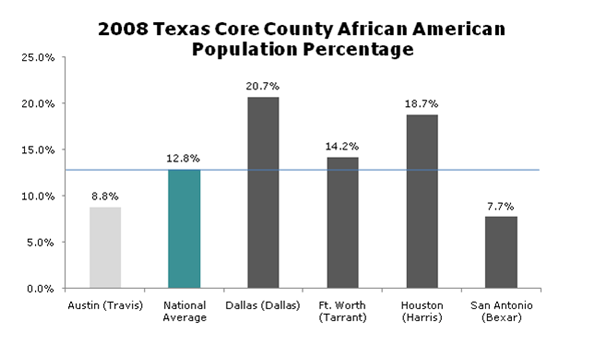

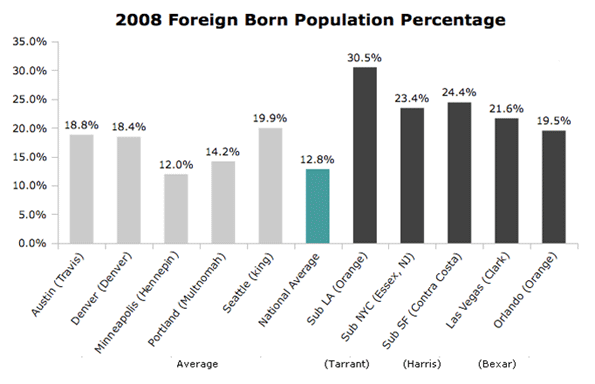

Yet such markets are exceptional. In most regions, the vast preponderance of homebuyers are either natives or long-term migrants. Their less glamorous tastes — notably access to affordable single-family dwellings — drives migration from one region to another. Over the past decade, and even since the crash, this has meant a general trend of migration from high-end, unaffordable markets to less expensive regions. In the U.S., for example, people have been flocking to the South, particularly the large metropolitan areas of Texas.

One factor driving this migration, the Demographia study reveals, is differing levels of regulation of land use between regions. In many markets advocacy for “smart growth,” with tight restrictions on development on the urban fringe, has tended to drive up prices even in places like Australia, despite the relatively plentiful supply of land near its major cities.

More recently, “smart growth” has been bolstered by claims, not always well founded, that high-density development is better for the environment, particularly in terms of limiting greenhouse gases. Fighting climate change (aka global warming) has given planning advocates, politicians and their developer allies a new rationale for “cramming” people into more dense housing, even though most surveys show an overwhelming preference for less dense, single-family houses in most major markets across the English-speaking world.

Limits on the kind of residential living most people prefer inevitably raises prices. As the Demographia study shows, the highest rise in prices relative to incomes generally has taken place in wherever strong growth controls have been imposed by local authorities.

Perhaps the poster child for “smart growth” has been the U.K. Long before the climate change debate, both of England’s major parties embraced the notion of strict constraints on suburban development — not only in London, but across the country. As a result, even places with weak economies are not as affordable as they should be. Liverpool, Newcastle and the Midlands have affordability rates higher than Toronto, Boston, Miami and Portland — and not much lower than those of New York or Los Angeles.

But the most remarkable impact of “smart growth” policies has been in Australia, which once had among the most affordable housing prices in the English-speaking world. Houses in Sydney and Melbourne, for example, are now less affordable than in London or San Francisco. Even secondary markets like Adelaide and Perth are more expensive than Toronto, New York, Los Angeles or Chicago. Most recently these policies have even caught the attention of the OECD, which linked overly regulated housing markets not only to the Great Recession, but to a continued slow economic recovery.

Compared with the U.K. and Australia, the U.S. housing market is more hopeful, with a host of regions — notably Houston, Dallas, Austin, San Antonio, Phoenix and Kansas City — with affordability rates around three and under. Low prices by themselves, of course, are no guarantor of success; in economically challenged places like Detroit and Cleveland, out-migration and high unemployment have driven prices down.

But in many, if not most, cases affordability has promoted economic and demographic growth. Generally speaking, affordable markets tend to draw migrants from overpriced ones, for example to Houston or Austin from Los Angeles or New York.

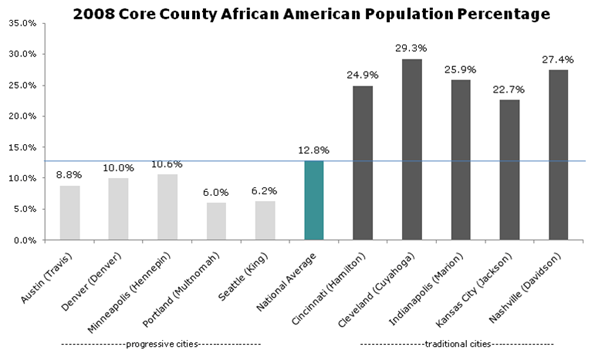

Nor is this necessarily a case of “smart” people heading to dense, expensive cities while the less cognitively gifted head to the low-cost regions — as news outlets like The Atlantic have claimed. In fact, the American Community Survey reveals that between 2007 and 2009 college graduates generally gravitated toward lower-cost, less dense markets — such as Austin, Houston and Nashville — than to the highly constrained, denser ones. Overall growth in affordable markets — with a ratio of three or four — among college graduates was roughly 5%; in the more expensive places , it was barely 3%.

How could this be, if everyone with an above-a-room-temperature IQ supposedly favors hip, cool, dense cities? Perhaps it’s because of factors often too small or mundane for urban pundits to acknowledge. Most people, particularly as they enter their 30s, aspire to a middle-class lifestyle — and being able to afford a house constitutes a large part of that.

So what does this tell us about future growth? Clearly affordability matters. Areas that combine strong income and job growth, along with affordable housing, are poised to do best. This will be particularly true once the economy recovers and a new generation of millennial buyers, entering their 30s in huge numbers over the next decade, start their search for a place where they can settle down and start raising families.

This piece originally appeared in Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.