Superficially at least, California’s problems are well known. Are they well understood? Apparently not.

About a year ago Time ran an article, “Why California is Still America’s future,” touting California’s future, a future that includes gold-rush-like prosperity in an environmentally pure little piece of heaven, brought to us by “public-sector foresight.”

More recently, Brett Arends’ piece at Market Watch, “The Truth About California,” is more of the same. California’s governor elect, Jerry Brown, liked this piece so much that he tweeted a link to it.

The optimist’s argument about California’s future ultimately hinges on the creativity of the state’s vaunted tech sector, in large part driven by regulation promulgated by an enlightened political class and funded by a powerful venture capital sector.

No fundamentalist evangelical speaks with more conviction or faith than a California cheerleader expounding on the economic benefits of environmental purity brought about by command and control regulation.

The more honest cheerleaders acknowledge that California has challenges, including persistent budget problems. Arends denies even the existence of a budget problem, demanding “Er, no, actually. It’s your assertion. You do the math.” Let me help you, Brett. The non-partisan California Legislative Analyst’s Office has done the math. You can find it here. They expect budget shortfalls in excess of $20 billion a year throughout their forecast horizon. This is on annual revenues of less than $100 billion.

Last week the numbers got even worse, as the Governor-elect, Jerry Brown, acknowledged. The deficit may now be as much as $28 billion this year, and over $20 billion for the foreseeable future. This is more than a nuisance. There’s a reason, after all, why California has among the worst credit ratings of any state.

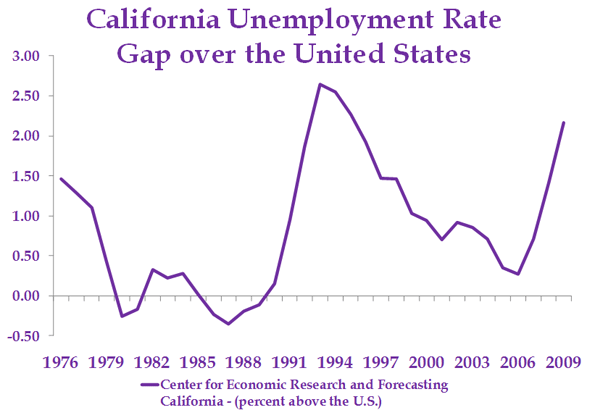

Most people outside of California haven’t drank from this vat of the economic equivalent of LSD-laced Kool-Aid. People know that a state is in trouble when it has persistent intractable budget deficits, chronic domestic net out-migration, and 30 percent higher unemployment than the national average. Indeed, California’s joblessness, chronic budget deficits, governors, and credit rating have made the state the butt of jokes worldwide.

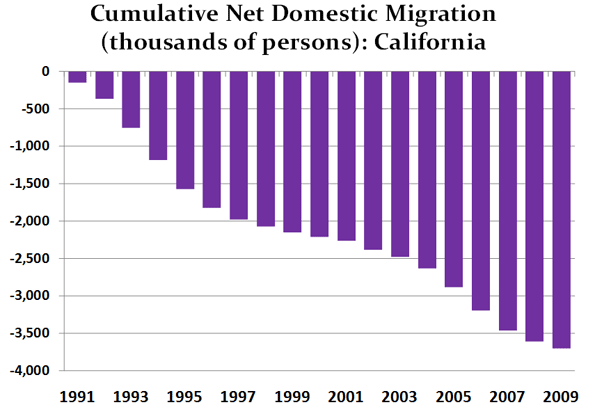

How bad are things in California? California’s domestic migration has been negative every year since at least 1990. In fact, since 1990, according to the U.S. Census, 3,642,490 people, net, have left California. If they were in one city, it would be the third largest city in America, with a population 800,000 more than Chicago and within 200,000 of Los Angeles’ population.

We’re seeing a reversal of the depression-era migration from the Dust Bowl to California. While California has seen 3.6 million people leave, Texas has received over 1.4 million domestic migrants. Even Oklahoma and Arkansas have had net-positive domestic migration trends from California.

Those ultimate canaries in the coal mine, illegal immigrants, recognize California’s problems. Twenty years ago, about half of all United States illegal immigrants went to California. Today, that’s down to about one in four.

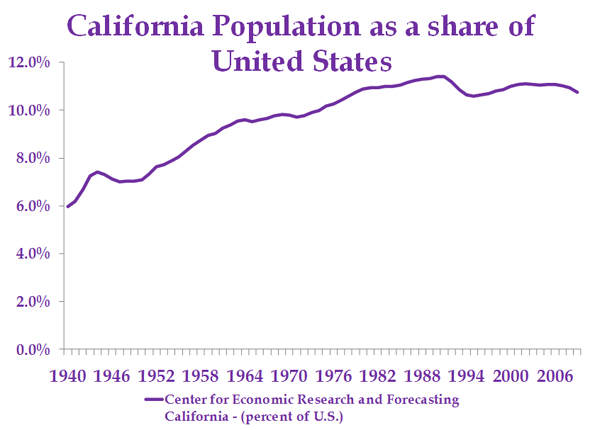

The result of these migration trends is that California’s share of the United States population has been declining.

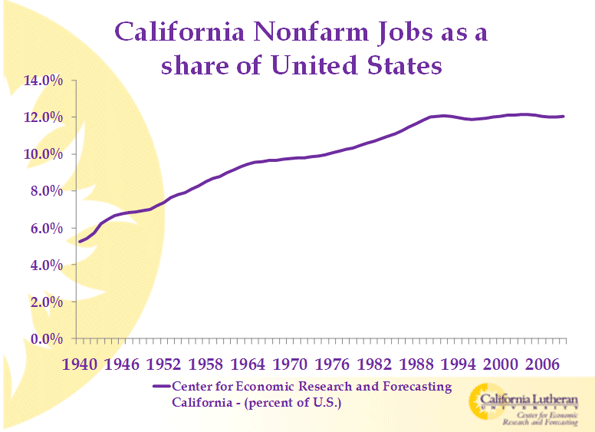

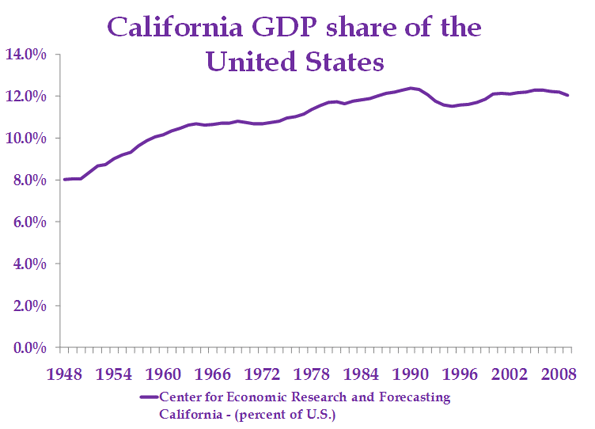

What do these migrants see that so many of California’s political class do not see? They see a lack of opportunity. California’s share of United States jobs and output has declined since 1990, and its unemployment rate has remained persistently above the United States Average, only approaching the average during the housing boom.

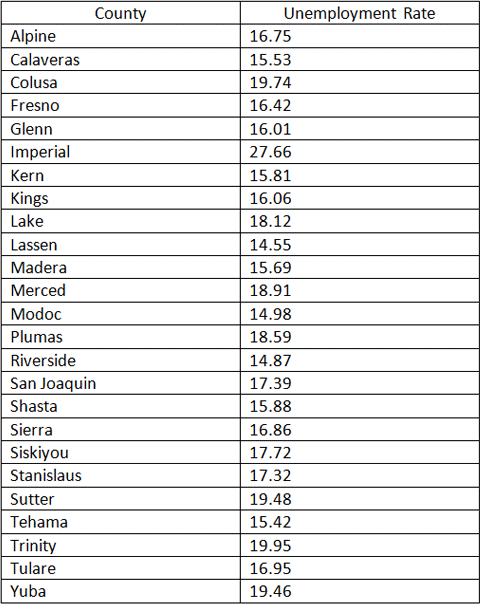

California’s unemployment is particularly troubling. As of October 2010, only two states, Nevada at 14.2 percent and Michigan at 12.8 percent, had higher unemployment rates than California’s 12.4 percent. California’s unemployment problem is particularly severe in its more rural counties. Twenty-five of California’s 58 counties have unemployment rates higher than Nevada’s:

These unemployment rates approach depression levels. Some will excuse many of them because they are in agricultural areas, but many assert that low Midwest unemployment rates are due to a booming agricultural sector. Which one is it?

California’s unemployment problems are not limited to rural and agricultural areas. Most of Riverside County’s population is very urban, yet the County’s unemployment rate is 14.87 percent. On December 7th, the Wall Street Journal listed the unemployment rates for 49 of America’s largest urban regions. California had six of the 19 metro areas with double-digit unemployment. These include such major cities San Diego, San Jose, and Los Angeles.

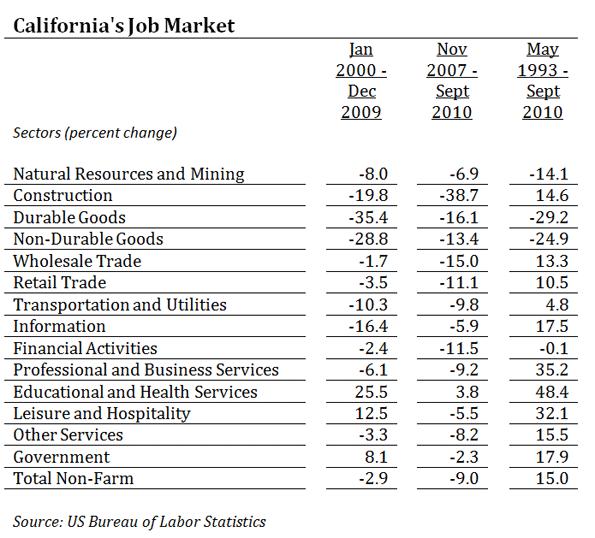

Just as rural areas are not California’s only depressed areas, agriculture is not California’s only ailing sector. From 2000 to 2009, the only California sectors to gain jobs were government, education and health services, and leisure and hospitality.

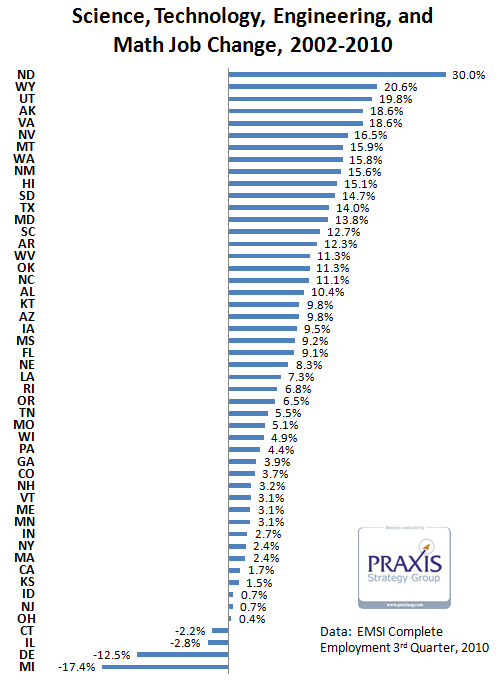

California’s cheerleaders claim that the state’s future is assured by a vibrant tech sector, but the data do not support that assertion. North Dakota’s Praxis Strategy Group has performed analysis by job skills. They compare Scientific, Technical, Engineering, and Math (STEM) jobs across states. Their analysis shows that California is the Nation’s ninth worst state in creating STEM jobs in post dot-com-bust years. It has produced far fewer new tech jobs than Texas, and far less on average, than the country over the past decade:

In this respect, California’s precipitous decline is really quite shocking. In just a couple of decades, California has gone from being America’s economic star, a destination for ambitious people from around the world and abundant with opportunity, to home of some of America’s most distressed communities. It has been a man-made, slow motion tragedy perpetuated by a political class that is largely deluded.

The cheerleader’s faith in command and control regulation and environmental purity is so strong they cannot see anything that contradicts that faith.

But that faith is misplaced. Joel Kotkin, Zina Klapper, and I performed an extensive review of the economic impacts of one of California’s most important greenhouse gas regulation, AB 32, and found that command and control regulation in general and AB 32 in particular is inefficient, cost jobs, and depress economic activity. California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office agrees, as evidenced by this report.

More depressing still are the growing ranks of what could be called “the resigned”. They simply have given up. These include a business leadership that is more interested in survival and accommodation than pushing an agenda for growth. Easier to get along here, and expand jobs and opportunities elsewhere, whether in other states or overseas.

Yet ultimately California’s future is what Californians make of it. No place on Earth has more natural amenities or a more benevolent climate. No place has a location more amenable to prosperity, located between thriving Pacific Rim economies and the entire North American market. No place has more economic potential.

But unless policy is changed, California’s future is dismal, with the specter of stubbornly high unemployment, limited opportunity, and the continued exodus of the middle class. California’s political class needs first to confront reality before we can hope to avoid a dismal future.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org.