The world’s biggest and most dynamic economy derives its strength and resilience from its geographic diversity. Economically, at least, America is not a single country. It is a collection of seven nations and three quasi-independent city-states, each with its own tastes, proclivities, resources and problems. These nations compete with one another – the Great Lakes loses factories to the Southeast, and talent flees the brutal winters and high taxes of the city-state New York for gentler climes – but, more important, they develop synergies, albeit unintentionally. Wealth generated in the humid South or icy northern plains benefits the rest of the country; energy flows from the Dakotas and the Third Coast of Texas and Louisiana; and even as people leave the Northeast, the brightest American children, as well as those of other nations, continue to migrate to this great education mecca.

The idea isn’t a new one – the author Joel Garreau first proposed a North America of “nine nations” 32 years ago – but it’s never been more relevant than it is today, as America’s semi-autonomous economic states continue to compete, cooperate … and thrive. Click on the thumbnail of our map to see our predictions for the job, population and GDP growth of these 10 regional blocks over the next decade, and read on below for more context.

View the map graphic at Forbes.com.

INLAND WEST

The Inland West extends from the foothills of the Rockies to the coastal ranges that shelter the Pacific Coast. This is the West as we understand it historically, a land of spectacular scenery: icecaps and dry lands, sagebrush, high deserts and Alpine forests. From 2003 to 2013, it enjoyed the most rapid population growth in the nation: 21%. It is expected to continue to outgrow the rest of the country over the next decade, as the area boasts the highest percentage of young people under 20 in the U.S.

Much of this growth was driven by a combination of quality of life factors — access to the outdoors and relatively low housing prices — as well as strong economic fundamentals. Over the past decade the area has enjoyed nearly 8% job growth, the strongest in the country, with the highest rate of STEM growth in the nation over the past decade. Boise, Denver and Salt Lake City have posted stellar employment growth due to the energy boom and growth in technology. The western reaches of the region — the inland parts of Washington, Oregon and California — have not done as well. These areas suffer from being “red” resource- and manufacturing-oriented economies within highly regulated, high-tax “blue states.”

THE LEFT COAST

The Northeast may still see itself as the nation’s intellectual and cultural center, but it is steadily losing that title to the Left Coast. This region sports a unique coastal terroir, with moderate temperatures, though it may be a bit rainy in the north. The climate requires less power than elsewhere in the country for heating and air-conditioning, making its residents’ predilection for green energy more feasible.

Over the past 20 years, the Left Coast — the least populous nation with some 18 million people — has rocketed ahead of the Northeast as a high-tech center. It has by far the highest percentage of workers in STEM professions — more than 50% above the national average — and the largest share of engineers in its workforce as well. No place on the planet can boast so many top-line tech firms: Amazon and Microsoft in the Seattle area, and in the Bay Area, Intel, Apple, Facebook and Google, among others.

Over the next decade, the Left Coast should maintain its momentum, but ultimately it faces a Northeast-like future, with a slowing rate of population growth. High housing prices, particularly in the Bay Area, are transforming it into something of a gated community, largely out of reach to new middle-class families. The density-centric land use policies that have helped drive up Bay Area prices are also increasingly evident in places like Portland and Seattle. The Left Coast has the smallest percentage of residents under 5 outside the Great Lakes and the Northeast, suggesting that a “demographic winter” may arrive there sooner than some might suspect.

CITY-STATE LOS ANGELES

Once called “an island on the land,” southern California remains distinct from everywhere else in the country. Long a lure for migrants, it has slipped in recent decades, losing not only population to other areas but whole industries and major corporations. The once-youthful area is also experiencing among the most rapid declines in its under-15 population in the nation. Yet it retains America’s top port, the lion’s share of the entertainment business, the largest garment district–and the best climate in North America.

THE GREAT PLAINS

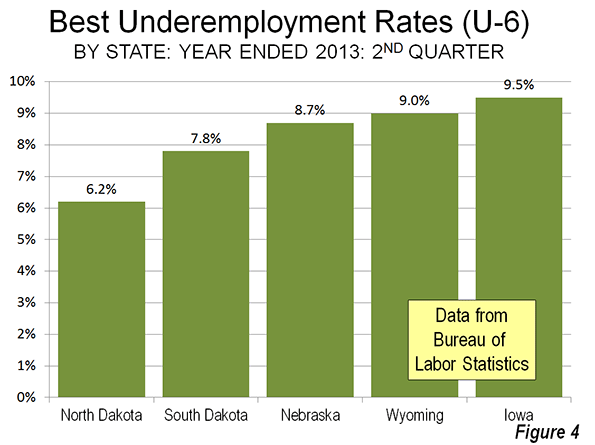

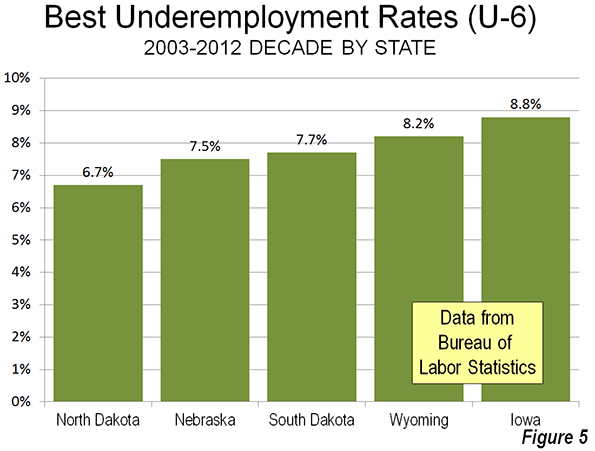

The vast region from Texas to Montana has often been written off as “flyover country.” But in the past decade, no nation in America has displayed greater economic dynamism. Since the recession, it has posted the second-fastest job growth rate in the U.S., after the Inland West, and last year it led the country in employment growth. The Dakotas, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Kansas all regularly register among the lowest unemployment rates in the country.

The good times on the Plains are largely due to the new energy boom, which has been driven by a series of major shale finds: the Bakken formation in North Dakota, as well as the Barnett and Permian in Texas. The region’s agricultural sector has also benefited from soaring demand in developing countries.

Most remarkable of all has been the Plains’ demographic revival. The region enjoyed a 14% increase in population over the past 10 years, a rate 40% above the national average, and is expected to expand a further 6% by 2023, more than twice the projected growth rate in the Northeast. This is partly due to its attractiveness to families — the low-cost region has a higher percentage of residents under 5 than any other beside the Inland West.

But outside of the oil boom towns, don’t expect a revival of the small communities that dot much of the region. The new Great Plains is increasingly urbanized, with an archipelago of vibrant, growing cities from Dallas and Oklahoma City to Omaha, Sioux Falls and Fargo.

Its major challenges: accommodating an increasingly diverse population and maintaining adequate water supplies, particularly for the Southern Plains. The strong pro-growth spirit in the region, its wealth in natural resources and a high level of education, particularly in the northern tier, suggest that the Plains will play a far more important role in the future than anyone might have thought a decade ago.

THE THIRD COAST

Once a sleepy, semitropical backwater, the Third Coast, which stretches along the Gulf of Mexico from south Texas to western Florida, has come out of the recession stronger than virtually any other region. Since 2001, its job base has expanded 7%, and it is projected to grow another 18% the coming decade.

The energy industry and burgeoning trade with Latin America are powering the Third Coast, combined with a relatively low cost, business-friendly climate. By 2023 its capital–Houston–will be widely acknowledged as America’s next great global city. Many other cities across the Gulf, including New Orleans and Corpus Christi, are also major energy hubs. The Third Coast has a concentration of energy jobs five times the national rate, and those jobs have an average annual salary of $100,000, according to EMSI.

As the area gets wealthier, The Third Coast’s economy will continue to diversify. Houston, which is now the country’s most racially and ethnically diverse metro area, according to a recent Rice study, is home to the world’s largest medical center and has dethroned New York City as the nation’s leading exporter. Mobile, Ala., seems poised to become an industrial center and locus for trade with Latin America, and New Orleans has made a dramatic comeback as a cultural and business destination since Katrina.

THE GREAT LAKES

The nation’s industrial heartland hemorrhaged roughly a million manufacturing jobs over the past 10 years, making it the only one of our seven nations to lose jobs overall during that period. But the prognosis is not as bleak as some believe.

Employment is growing again thanks to a mild renaissance in manufacturing, paced by an improving auto industry and a shale boom in parts of Ohio. The region has many underappreciated assets, such as the largest number of engineers in the nation, ample supplies of fresh water and some of the nation’s best public universities. With fifty-eight million people, it boasts an economy on a par with that of France.

Yet we cannot expect much future population growth in the Great Lakes, the second most populous American nation. Its population is aging rapidly, and the percentage under 5 is almost as low as the Northeast.

THE GREAT NORTHEAST

The Northeast–which excludes the city-state of New York–has been the country’s brain center since before the American Revolution. This region is home to some 41 million people, and leads the nation in the percentage of workers engaged in business services, as well as in jobs that require a college education. With average wages of $76,000, $19,000 above the national average, the area boasts a GDP of $2.2 trillion, about equal to that of Brazil.

The Northeast is one of the country’s whitest regions — Anglos account for over 70% of the population — and one of the wealthiest. In many ways, it resembles aging Western Europe in its demographic profile. The Northeast is the most child-free region outside the retirement hub of south Florida. Coupled with sustained domestic out-migration, its population growth is likely to be among the slowest in the nation in the decade ahead.

Good thing its residents are highly educated — diminishing numbers and the consequent decline in political power suggest that the Northeast may need to depend more on its wits in decade ahead.

CITY-STATE NEW YORK

The Big Apple’s much heralded comeback has assured its place as one of the world’s great global cities. But the city faces challenges in terms of soaring indebtedness, rapid aging, a weak technical workforce, expensive housing and high taxes. It also will struggle with competition from rising cities of the other nations such as San Francisco, Seattle, Washington, D.C., and Houston, each of which threatens New York’s traditional role in key sectors of the economy.

THE SOUTHEAST MANUFACTURING BELT

At the time of the Civil War the southeastern United States was both outpeopled and outmanufactured. Today the Southeast, is the largest region in terms of population (60 million) and is establishing itself as the country’s second industrial hub, after the Great Lakes.

It is attracting large-scale investment from manufacturers from Germany, Japan, and South Korea. Although most of the region still lags in educational attainment, the education gap with the Northeast and Great Lakes is slowly shrinking. The population holding college degrees has been expanding strongly in Nashville, Raleigh, Birmingham, Richmond and Charlotte.

More babies and the migration of families, including immigrants, to this low-cost region suggest an even larger political footprint for the Southeast in the decades ahead. Population growth has been more than twice as fast since 2001 as in the Northeast, a trend that is projected continue in the next decade. The region looks set to become smarter, more urban and cosmopolitan, and perhaps a bit less conservative.

CITY-STATE MIAMI

Greater Miami often seems more the capital of Latin America than it does an American region. Its population is heavily Hispanic, and trade, finance, construction and tourism tend to focus southward. But Miami faces the constraints of an aging, and largely childless, population–which means it will continue to rely on newcomers both from abroad and from the colder regions of the U.S.

This story appears in the September 23, 2013 issue of Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Mark Schill is Vice President of Research at Praxis Strategy Group, an economic development and research firm working with communities and states to improve their economies.