Walt Disney’s first version of Tomorrowland came to life in 1955. The attractions were geared towards the space age, and towards the future of transportation that Disney believed scientists of his time were about to create. The imaginary world was intended to “give you an opportunity to participate in adventures that are a living blueprint of our future.” When Tomorrowland opened, its showpiece was the TWA Moonliner exhibit, which contained the Rocket to The Moon; later, its Flight to the Moon gave another perspective. Once Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, these Disney attractions were no longer science fiction.

Accommodating the reality of moon flights, the Flight to the Moon was updated to Mission to Mars. Only 14 years after the park opened, the space age that Walt Disney had imagined was becoming a reality. Before President Eisenhower had signed the Interstate Highway legislation, Autopia allowed riders to experience Disney’s interpretation of what the system would one day be like. Autopia accurately envisioned the future of America’s soon to be multilane limited-access highways.

Another addition to Tomorrowland was the Monsanto House of the Future, added in 1957. Items such as picture phones, television remote controls and a microwave oven familiarized many visitors with these ideas for the first time. Tomorrowland continued to prove itself as an innovative predictor of the near future.

Downfall of the Futuristic Tomorrowland – Unlike its predecessor, Mission to Mars wasn’t replaced after becoming a reality. Instead, Red Rockett’s Pizza Port, a space themed pizza parlor, took its spot in the 1998 refurbishment. Disney didn’t have enough confidence in a real mission to Mars to update or revamp the ride. Instead of updating it, Disney was essentially saying that a successful human mission to mars was not a fathomable idea.

At the same time, Disneyland was cutting back on refurbishment in the Carousel of Progress. This attraction took viewers on a journey through the eyes of a “typical” American family exploring life through the dawn of electricity and other technological advancements. Periodic updates were necessary to keep up with the times of its audience. The first version lasted three years, the second six years, and then two years, ten years, and nine years respectively. The attraction has been periodically closed, but hasn’t been significantly modified in 18 years. This increased changeless period waves another flag of concern, as it demonstrates Disney’s view that there has been no noteworthy progress in almost two decades.

Rather than foreshadowing, like the early Tomorrowland did, current Tomorrowland is opening attractions like Buzz Lightyear Astro Blasters, where passengers shoot targets modeled from Toy Story or a submarine voyage where passengers go “under the sea” to spend time with characters from Finding Nemo. Concentrating on movies expresses that Disneyland has no expectations to focus on the future. The most recent display of this is the sequel of the Star Wars themed motion simulator, Star Tours: The Adventures Continue. Instead of replacing the out of date ride with a new, innovative idea, the same idea from 1987 with newer graphics sufficed. While in the past a bright vision of the future both inspired and guided Disney’s early Tomorrowland, today’s innovative standstill forces the Disney company to draw the focus off the future’s possibilities and gear the theme park towards animations.

Disney Movies – Select movies demonstrate Disney’s continual hope in the space era. The first Zenon movie was set in the year 2049 and took place in the orbiting space station where Zenon’s family resided. Even though this movie was released in 1999, much after Walt Disney’s death, his visions of a space era are directly displayed. Since Zenon, Disney has released another movie with humans residing in an orbiting space station. In 2008’s Wall-E, the humans were forced to evacuate to space in 2105 when the earth became unsafe for human life.

While Disney is keeping their space era predictions, they are continuously projecting them further into the future. Originally, 1955’s Tomorrowland envisioned space development for 30 years in the future. 1999’s Zenon gave the orbiting space home 50 years to become reality, and 2008’s Wall-E gave nearly 100 years until humans began to live in space. This growing gap shows that although the idea of space development stays near to Disney’s heart, the company’s pessimism about the technological advancements of society certainly exists.

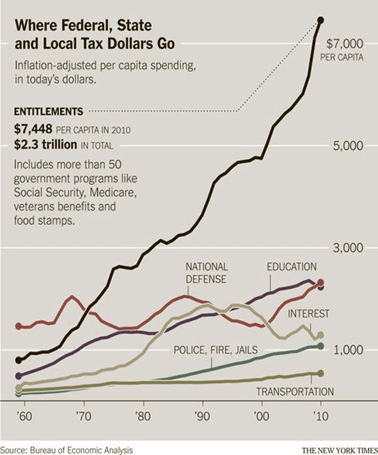

Justified Pessimism? – Disney’s pessimistic attitude towards the rate of current advancement comes from a place of truth. New, revolutionary ideas were coming out on a consistent basis in the mid 1900s during Walt Disney’s generation, but near the late 1900s progress as a whole slowed down. Rather than innovating new and fresh ideas, the current generation fine-tunes the revolutionary ideas of their predecessors.

A kitchen today won’t differ too grandly from one in 1980. Although most appliances may be higher quality, they were still there in both eras. Comparing kitchens from 1980 and 1940 shows vast differences. Not only did appliances get sleeker, but you will also not find a microwave, a food processor nor Tupperware anywhere. These are only a few of the many kitchen changes that came to life in that time period. The kitchen only represents a small sector of technology and advancement, but the trend it represents stands.

The oldest members of today’s world lived through the invention or development of the airplane, skyscraper, suspension bridge, radio, television, antibiotics, atomic bombs, and interstate highways. The mid-life individuals went through the first moon landing, the popularization of personal computers and invention of search engines, biotechnology, and cellphones. Participants of the younger generation have seen much up- tuning of these devices, but are greatly lacking in brand new revolutionary inventions.

Facebook and the iPhone may be classified as the monumental inventions of the past decade. While they improved the social networking and convenience of society, can they really be compared the monumentality of the first airplane or personal computer? Previous milestones are being expanded and fine-tuned. Rather than thinking of new revolutionary discoveries, the current generation attempts to fix the old ones. Technology seems to be hitting a very worrisome plateau.

Walt Disney was justified in the optimism he displayed with 1955’s version of Tomorrowland. He belonged to the generation of innovation, and naturally expected society to continue flourishing. He didn’t foresee the technological plateau blocking Tomorrowland from becoming reality. Currently, Disneyland is trying to divert notice from the lack of change by adding more animated features to Tomorrowland. The new rides help visitors feel as if Tomorrowland is still continually changing, and that progression hasn’t slowed down.

However, it’s only a matter of time until the whole sector becomes a Disney themed montage. If technological development continues at this rate, Tomorrowland may as well combine with Fantasyland as a childish delusion from the past. As displayed by the modern developments of both Disney movies and Disneyland, the once flourishing future that Disney envisioned for the world is coming to a rapid halt.

Flickr photo by jnocca93:

Entrance to Tomorrowland at Disneyland, California.

Zohar Liebermensch is a sophomore studying business administration emphasizing in economics with minors in computational sciences and the university honors program at Chapman University. Born in Israel, she moved to northern California when she was a toddler and has been enjoying Orange county for the past two years. She is vice president of the Chapman chapter of the National Society of Leadership and Success as well as a member of the university’s soccer team.