American and European planners have long sought to improve the “jobs-housing” balance, seeking to place residents and jobs within walking or cycling distance. Of course, planners don’t place people anywhere. Not surprisingly, their efforts have largely failed, from the new towns of the London area, where people travel about as far to work as anywhere else, to fabled failures of Stockholm, where high rise housing close to suburban employment centers now houses migrants who tend to have far lower incomes than native Swedes.

In the time of Mao Zedong, China had achieved perhaps the ultimate in the jobs-housing balance. Companies provided housing for their workers, who were able to walk to their jobs in the same compound. However, the economic reforms instituted by Deng Xiaoping and his successors has led to an abandonment of this model (Danwei housing) and millions of Chinese households have been lifted out of poverty into affluence. Most Chinese households do not aspire to “living on top” of the factory or office.

and his successors has led to an abandonment of this model (Danwei housing) and millions of Chinese households have been lifted out of poverty into affluence. Most Chinese households do not aspire to “living on top” of the factory or office.

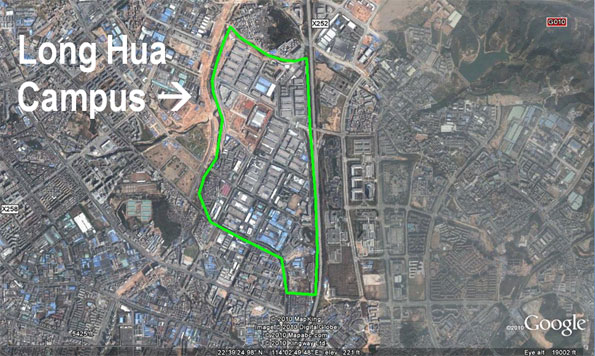

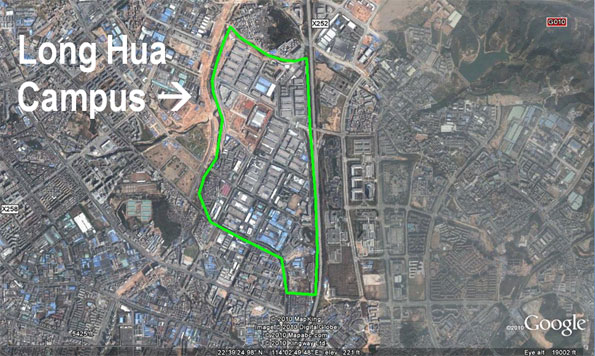

Foxconn (Hon Hai Precision Industry), one of the world’s largest companies, is among the last to provide large amounts of housing to its workers. In its Shenzhen “Long Hua Campus,” which covers only one square mile, Foxconn employs 450,000 people (Figure). They are housed on the campus or nearby in company provided units.

Shenzhen directly borders Hong Kong and Dongguan, which borders the Guangzhou-Foshan urban area. All together, these contiguous Pearl River Delta urban areas, along with others down the western shore to Macao have nearly 50 million people, more than live in any geographic area of the same size anywhere else in the world. These Guangdong province urban areas, along with the special economic regions of Hong Kong and Macau have become one of the world’s leading manufacturing and export areas. Shenzhen itself has been estimated to have a population of between 10 million and 15 million, depending on how the migrant workers are estimated. Shenzhen and other major manufacturing centers of China are estimated to house as many as 200 millions migrants from other parts of China (especially rural areas), coming to work in jobs that pay far higher wages than can be earned at home.

Foxconn itself is the world’s largest manufacturer of consumer electronic technology, producing Apple’s I-Pod and I-Phone and making products for Dell, Hewlett-Packard, Sony, as well as the Nintendo, Wii entertainment systems.

Foxconn itself is the world’s largest manufacturer of consumer electronic technology, producing Apple’s I-Pod and I-Phone and making products for Dell, Hewlett-Packard, Sony, as well as the Nintendo, Wii entertainment systems.

According to a report in The Wall Street Journal, Foxconn has plans to abandon its Danwei housing and move away from its “perfect” jobs-housing balance to the spatial arrangements that Chinese, Americans and Europeans routinely choose — to work where they like and live where they like.

Foxconn has had its share of difficulties. There have been the multiple employee suicides at the Long Hua Campus. The company has faced rising costs in its Pearl River Delta operations, including higher wage costs. In its attempt to retain competitiveness, Foxconn is seriously rethinking its business model and appears likely not only get out of the housing business, but will also move many of its operations into central and western China, where costs and wages are lower. This also makes sense in relation to government policy, which seeks to develop the center and west.

Overall, Taiwan headquartered Foxconn employs 920,000 people in China, the equivalent of the entire work force in the Portland or Kansas City metropolitan areas.

Foxconn plans to increase its workforce in China from 920,000 to 1,300,000 and intends for many of its employees to be in new facilities in places like Chengdu (capital of Sichuan), Wuhan (capital of Hubei), Zhengzhou (capital of Henan) and Chongqing (capital of the provincial level Chongqing municipality). Foxconn’s decentralization, and the location of other new and expanded businesses in the center and west is strongly supported by China’s substantial infrastructure investment. The nation already has more than 40,000 miles of interstate equivalent highways. When all of the gaps are completed, trucks will be able to reach east coast ports from Zhengzhou or Wuhan in about days drive and little more than two days from Chongqing and Chengdu.

At the same time, corporate executives can get to Beijing, Shanghai and the Pearl River Delta and other East Coast urban areas in 2.5 hours or less through some of the world’s most modern airports.

Finally, the more decentralized operations will allow the migrant workers to live much closer to their homes, rather than having to travel all the way to the East Coast. This will make more frequent visits to rural villages and families possible.

—-

Photo: Wuhan (photo by author)