Californians attend innumerable conferences on housing and economic growth. Year after year, in counties across California, the same people show up to say and hear the same things. Mostly what they say and hear is naive, and nothing ever changes.

I was reminded of this when I saw a report on what appears to have been a typical conference at the Harris Ranch on Growing the Central Valley Economy.

There is no doubt that the Central Valley economy could use some economic growth. After years of paying a disproportionate share of the costs of California’s coastal-driven energy, environmental and water regulations, the Valley’s economy is suffering. Poverty is rampant, as California leads the nation with a three-year average poverty rate of 23.4 percent according the Census Bureau’s most recent comprehensive poverty measure.

The Valley and some other inland areas are the primary reason California leads the nation in poverty and inequality. Throughout the Valley, economic growth is anemic. It’s negative in some areas. Some counties are seeing declining populations.

Conferences, at least the typical California conference, won’t help. They only serve to provide a low-cost means to salve the participants’ consciences, allowing them to feel that they are doing something.

Consider the recommendations that came through the report:

Creative thinking from the public policy sector

You can bet your net worth that you will hear about creative thinking or thinking outside the box at every California housing or economic development conference. At best, it doesn’t mean anything. If it does mean anything, creative thinking from the public policy sector is the worst thing that could happen.

Public policy sector creative thinking is what has created the San Joaquin Valley’s stagnant economy and California’s poverty and inequality in the first place. California’s ruling elite are proud of California’s regulatory quagmire. No one could have imagined 20 years ago how successful they would be in putting it in place. Today, it remains unduplicated by any state, but Oregon is trying.

The public sector does not create jobs or wealth, although it can provide preconditions through infrastructure development or contracts. But government is not the source of innovation or wealth creation. That comes from entrepreneurs, whether in the once-dominant aerospace industry or the early days Silicon Valley’s world-leading tech sector. It won’t create any in the future.

The best that government can do is to get out of the way of innovators—that means stream-lining the regulatory process and protecting property rights, in order to provide a predictable business environment.

Let’s hope we don’t see more creative thinking from the public policy folks.

Putting a “face” on the Valley and individual lives affected, emphasizing the continuing drought, pending fracking legislation, and burgeoning trade and logistic sectors in the seven-county region known as the San Joaquin Valley

I think the idea is that if the coastal elite could just see the impacts of their policies, they would change those policies to allow more economic vigor in the Valley. The naivety is touching, and shockingly naive.

Let’s face it, California’s coastal elite likely care more about some Minnesota dentist’s shooting a lion than they care about the lives of Valley residents. Their policies are there to save the world. If they cause some inconvenience for people in the Valley, well that’s just the cost of progress.

It might be different if they thought their policies would impact their own incomes. Their policies don’t. Tech sector people know their incomes come from all over the world, and they just relocate plants, call centers, tech support and even development outside of California if costs become too high. There is a reason that the Silicon Valley no longer is building more of the chip factories for which it was named.

The retired coastal elite’s income is mostly independent of California’s economy. Once again, the checks come from someplace else.

Accessing and employing the most effective tools from science, engineering and technology to responsibly advance technological applications

Yep, and motherhood is a wonderful thing. Technology and applications will advance, regardless of what happens in the San Joaquin Valley. How is this supposed to help the Valley? California has priced itself out of competitive tradable goods production. That’s why Intel, Apple, Facebook and others are spending billions expanding outside of California.

Technology will benefit Valley residents, but it won’t be a source of economic growth until the Valley has a competitive cost structure. And that cannot happen until the state takes its foot off the valley’s neck.

Building coalitions to ensure adequate resources and investment in the Central Valley during what is likely to be a dramatic transition period

Coalitions are another topic that comes up in every California conference. We’ve heard this for decades, and nothing has happened.

All that coalitions, at least as they materialize in California, can do is advocate. Most often, they advocate to the government. Since governments are the source of the problem and not the source of economic growth and wealth, this not an effective strategy. The coalitions might extract some wealth from someone else, but they are not going to create economic vigor.

Focusing locally on training and retaining that will help boost opportunities for employment and contribute to an improved quality of life as the region continues its transformation to a progressively more sustainable future

This is another thing you hear constantly California conferences. Education and training are something that we have chosen to do for our young people. It can be an economic development tool. In California today, though, education is not an economic development tool.

San Joaquin Valley graduates of high school or college can’t get jobs in the Valley. The Valley’s unemployment rates are way above the State’s even in good years. More individuals with degrees won’t change this. All it means is that Texas, Arizona, Utah, and other states will have a better pool of California workers to supply their economies. We may feel a moral obligation to educate, but it’s not a local economic development tool.

What Could Work?

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) was originally enacted to protect California’s pristine natural environments. Since then it’s evolved into a tool which allows almost anyone to stop or delay just about any project. In fact, the threat of a CEQA case is often wielded by project opponents in order to extort concessions from companies.

CEQA dramatically increases the uncertainty and costs associated with California projects. It needs to be rewritten to achieve its original purpose while limiting its use as a tool for maintaining the status quo.

California’s other regulations that most hurt economic growth are either environmental or are designed to bring in “stakeholders .” All need to be evaluated on a cost-benefit basis.

Chapman University researchers have presented compelling evidence that California’s greenhouse gas regulations have almost no impact on global carbon levels, but we know they have considerable costs.

Regulations designed to bring in “stakeholders” effectively grant almost everyone veto power over most projects. You could hardly design a more effective method to slow or stop growth.

Politically, there is no chance of making necessary regulatory revisions anytime soon. There is hope, though. California’s minority caucus recently stopped proposed regulation mandating a 50 percent decrease in California’s use of gasoline. The minority caucus’ constituents are California’s primary regulatory victims. It was good to see them stand up for their constituents. I hope to see more of it in coming years. That will be far more effective than another conference.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org.

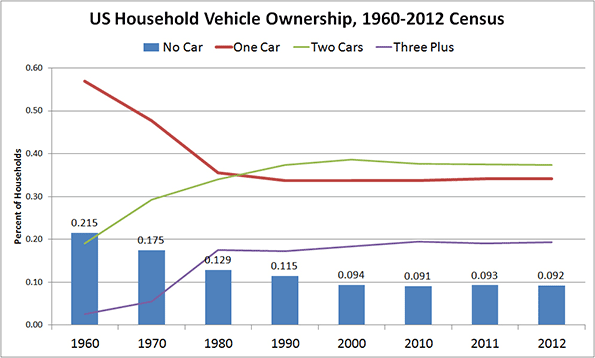

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5.

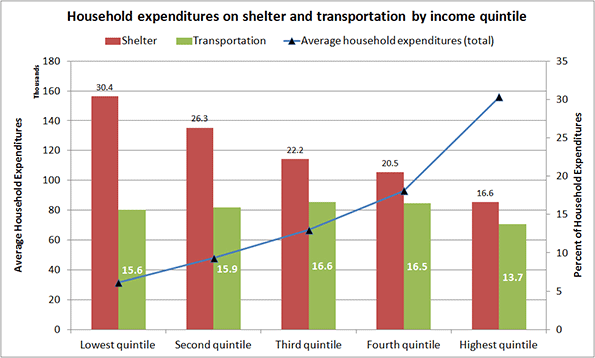

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5. Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012.

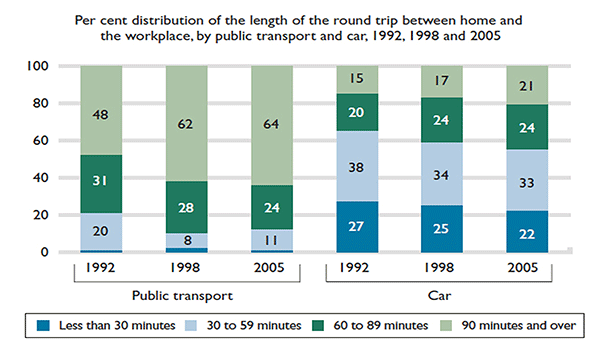

Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012. Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005.

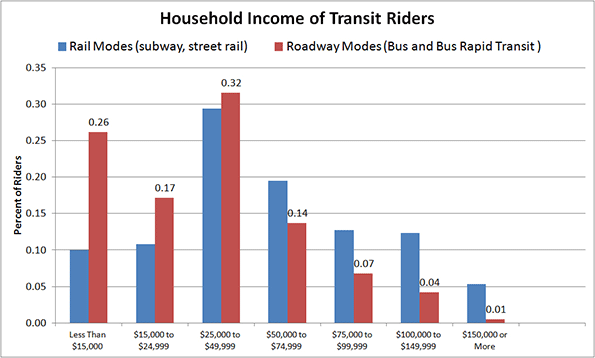

Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005. Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007.

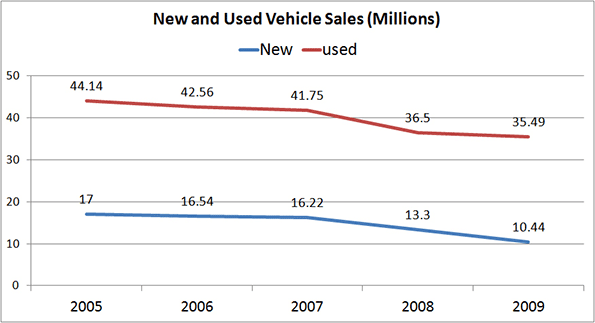

Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007. Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010.

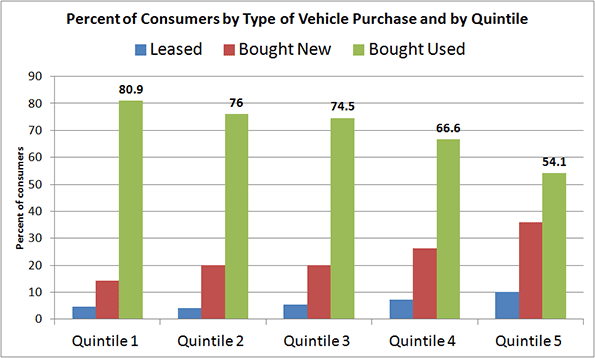

Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010. Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.

Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.